Breaking ice

Thick ice on the Mohawk may result in ice jam flooding when spring arrives

As we emerge from the depths of winter, days are warming and the deep freeze of January appears to be behind us. In front of us is the breakup on the Mohawk River, and issues related to ice jams and the floods that they can cause. Building flood resilience in our river-lining communities was one of the goals of the Reimagine the Canals effort, and addressing ice jamming on the lower Mohawk was an important element of this flood mitigation [1,2]. In December 2020, the Governor announced a component of that effort that involves breaking ice with tugs in the Schenectady pool, a reach of the Mohawk River between Lock 7 and Lock 8 that sees chronic and damaging ice jams and related floods [3,4,5,6]. The 2021 winter was mild, so the first year of this ice-breaking experiment ended without fanfare. The 2022 winter, however, has been much colder and we now have some serious ice to contend with. As a result, the Margot, a tug owned by NY State Marine Highway Transportation Company (Troy, NY), has been in the river breaking ice in an effort to mitigate ice jams. The ice-breaking is part of an experiment to better understand ice thickness and winter operations. As explained below, ice-breaking may help lessen the impact of two chronic jam points, but it will not eliminate ice jams. This post explores the ice jam issue, and addresses part of the complexity of the problem.

The Margot tug breaking ice on the Mohawk River just upstream of the Vischer Ferry dam (Photo: JI Garver, 2 Feb 2022).

Ice jams on the lower Mohawk are well studied and we have a pretty good understanding of the mechanisms that result in jams and related flooding. Vulnerable communities include low-lying areas in Rexford, Alplaus, Glenville, Scotia, and the Stockade of Schenectady, and upriver in parts of Rotterdam Junction. To monitor, watch, and study ice jams, the USGS has built one of the most comprehensive and sophisticated ice jam monitoring systems in the Northeast. This is the Ice Jam Monitoring Network and you can access the Jam cam and ice monitoring page here.

I have written a number of short papers about ice jams on the Mohawk, including the 2019 jam [3], the 2018 jam [4,5], and older events [see refs in 6]. In 2018 I worked with colleagues to map and measure the thickness of the enormous 27-km long ice jam of 2018 [5]. Once that jam lodged in place, we mapped the toe, or jam point, in the Rexford Knolls using photogrammetric mapping from hundreds of photos taken by a drone. This model of the ice jam allowed us to estimate ice thicknesses between 10 and 24 feet at the chronic jam point caused by the narrow channel in that reach of the river [6].

Ice jams occur on many rivers in the Northeast, and given the temperatures in the last month, we could predict that this may be a busy spring because ice thickness is an important ingredient in the ice jam recipe. We know the conditions for breakup: 1) sharp warming; and 2) increased flow (or “discharge”) in the river. When this happens, water levels rise, the ice breaks, and it tries to flow downriver. If the flowing broken ice, referred to as an ice run, encounters resistance, then ice jams can occur, and when they do, back-up flooding may endanger low-lying communities. Thick ice exacerbates the problem, and some of the most historic and damaging ice jams have been driven by thick ice from a cold winter. The second part of the problem is the identification of specific chronic jam points where the flowing rubble ice gets caught up as it tries to run downriver. In an ideal world the river channel would be straight, the same width, and the same depth everywhere. We do not live in an ideal world.

In the lower Mohawk, there are several chronic jam points, and these are almost all in places where the river channel narrows, so rubble ice in an ice run has trouble getting through. An ice run is like fans going to a baseball game who all have to slow down to pass through the turnstiles to get into the stadium. The primary hazard on the lower Mohawk is the nearly 10-mile-long Schenectady pool, which is between Lock 7 in Niskayuna and Lock 8 in Glenville.

Two important physical features result in chronic jamming in the Schenectady pool. One is inherited from the end of the ice age: the bedrock gorge in the Rexford Knolls. This steep-sided section of the river is narrow and deep, largely due to a re-arrangement of the River about 10,000 years ago. The narrowest channel is in front of GE R&D and KAPL where it is about half its normal width. This is one of the most “productive” chronic jam points on the lower Mohawk (see map). The other physical feature of importance is the impoundment caused by the Vischer Ferry Dam (VFD). This dam has a permanent pool with slow-moving water (nearly static in the winter), which favors the development of thick sheet ice. When ice come barrelling down the river from the upper Mohawk Valley, everything slows down and piles up in the more slowly moving water in the Schenectady pool.

When an ice run encounters a narrow reach in the river several things may conspire to cause an ice jam. One is that there are lateral (or sideways) forces that squeeze the ice chunks together - this causes the ice to imbricate and thicken. The ice run is being forced downstream by the flowing water. But it also encounters resistance by unbroken thick sheet ice in front of the jam point. Thus when evaluating the issues of jam points we need to consider overall downstream flow, later squeezing, and impedance from what is up ahead. The ice-breaking is aimed at weakening the sheet ice in front of the jam point, so that the ice run can break through and continue downriver. Computer modeling done by colleagues at Clarkson University shows that removal of the sheet ice in front of the Knolls jam point lessens the severity of jamming at the point [7]. This type of intervention can only occur before breakup. Once breakup occurs no icebreaker activity will occur: it is too dangerous because jams back up water that can be released quickly in a surge of water.

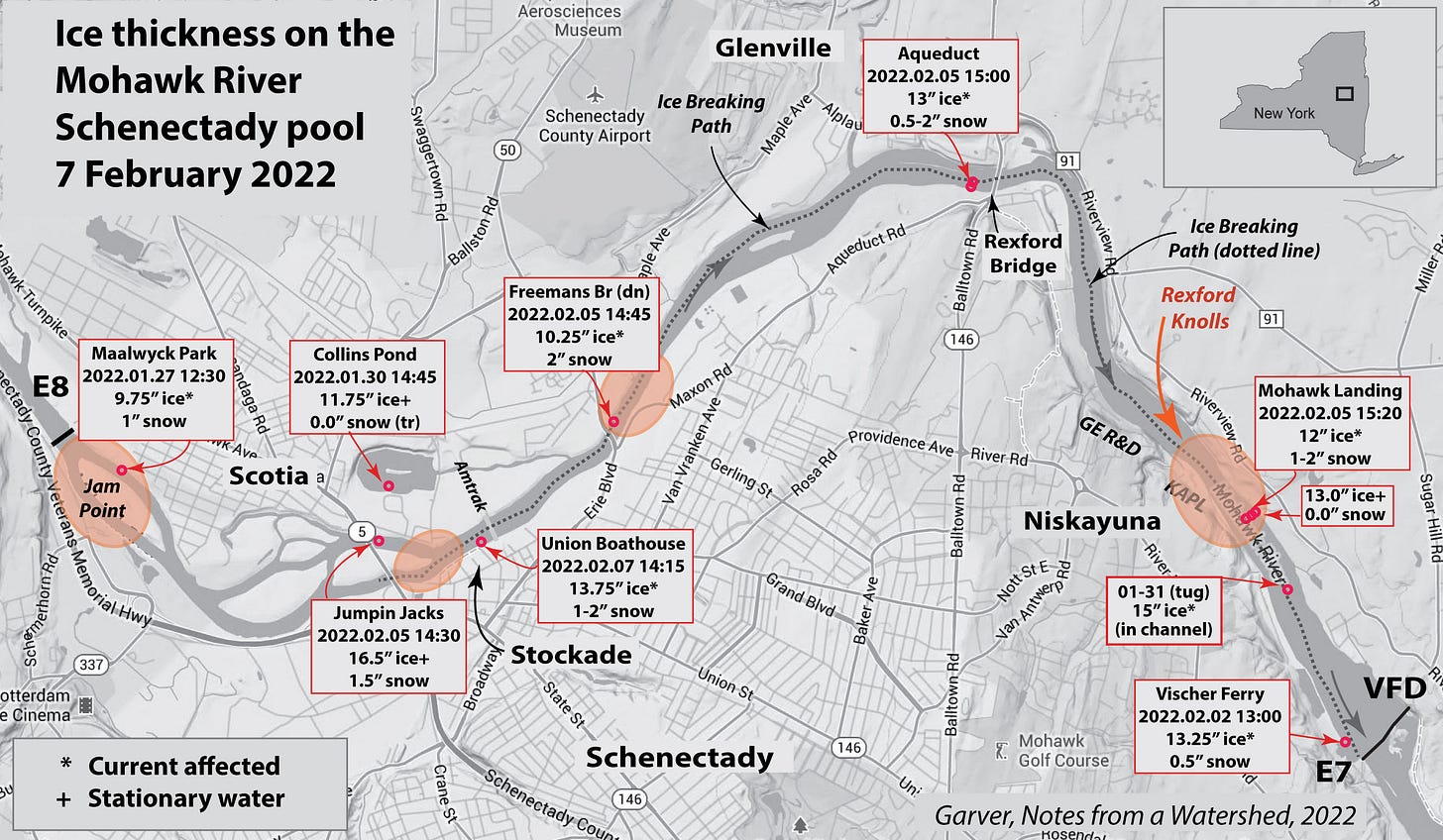

Current ice thickness. Much of the sheet ice in the Schenectady pool is over a foot thick. Since the cold snap in January, I have been using an auger at seven locations to measure ice thickness in the Schenectady pool (see map). Ice thicknesses on the River are highly variable, and in some places moving water is actually ice free: I do not recommend walking on the River, ever. In my most recent measurements the thickest ice is 16.5” in the static water in front of Jumpin’ Jacks, and at the Freeman’s Bridge it is 10.25” thick. But most locations have between 12 and 13” of ice, and this is a red flag for possible ice jams in the future. Thick ice is stronger, and therefore able to support more significant jams.

Map of ice thicknesses in the Schenectady pool measured from late January to early February. Areas with orange shading denote those locations that are chronic ice jam points: perhaps the most important and significant is the narrow Rexford Knolls about a mile and a half upriver from the Vischer Ferry Dam (VFD).

Given the thickness of ice out there now, we need to prepare for ice jams, especially if the weather undergoes a sharp warming. The best case scenario would be cold weather and only gradual warming so that the ice stays put, but slowly melts in place. Maple-syrup weather is ideal: cold freezing nights and moderate temperatures above freezing during the day. I refer to this as the slow burn, and it is ideal because it is possible that by the time the ice does break, it's just too weak to cause problems. But if the warm up is sharp, and accompanied by rainfall and significant snow melt (combined to result in high runoff and rising river levels), we can expect ice jams to form.

An 18” long ⅞” bit on a brace is used to drill the ice to determine ice thickness. Here a hole is being drilled in front of Jumpin’ Jacks in Scotia. The Stockade is in the distance (Photo: JI Garver, 30 January 2022).

Hazard mitigation involves those actions aimed at reducing or eliminating the impact of a hazard on society. With ice jams and related flooding there are a whole host of mitigation strategies that may lessen the impact, but we have not discovered a silver bullet that will eliminate the threat. So mitigation is focussed on those strategies that will lessen the impact, and this is the situation with ice-breaking.

In 2019 the Reimagine the Canals task force coordinated an Ice Jam Mitigation Panel through NYPA (NY Power Authority, which oversees Canals) that looked into mitigation strategies for ice jamming on the lower Mohawk River [2]. The Panel, which I am on, focused primarily on the Schenectady pool (between the Vischer Ferry Dam/Lock E7 and Lock 8 in Glenville/Rotterdam). The Ice Jam Mitigation Panel evaluated a number of possible direct interventions, but in the end, four primary strategies emerged that were appropriate to the specific problem here in the Schenectady pool:

Ice breakers to physically break up sheet ice at chronic jam points

Obermeyer Spillway Gates on the Vischer Ferry Dam to flush out ice floes.

Re-profiling the river channel through sediment removal to alleviate choke points.

Removal or modification of bridge abutments.

The panel also recommended a warning system that would alert residents that ice jamming was possible, imminent, or ongoing. Following the release of this Ice report, river reprofiling was eliminated due to cost and issues with contaminated sediment (read about sediment issues here in “Radioactive fish”), and there are no offending bridge abutments that need mitigation. The oft-cited Amtrak bridge in the Stockade is not a jam point, and its design actually breaks ice up as demonstrated repeatedly from the USGS Jam Cam on the Union College Boathouse (see the USGS Jam cam and ice monitoring page here). Immediately upstream, however, the old Burr bridge abutments are an issue: we attributed that constriction in river channel width to the damaging ice-jam-induced flooding of 1996 [6].

Thus from a practical perspective, we are left with ice-breaking and the installation of pneumatic gates (Obermeyer) on the VFD that will allow the level of part of the dam to be dropped instantaneously, hence flushing water and ice out of the lower part of the Schenectady Pool. This latter intervention strategy may take some time to develop (but is discussed more fully here in “Ice breakers on the Mohawk”). If the dam is modified, we may be considering break-and-flush to remove ice. However, at this point we are focused on doing these initial experiments with ice-breakers and improving the early warning system.

Canal statement. Current ice-breaking efforts by the tugs is an important experiment aimed at understanding operational procedures and variation in ice thickness, and hopefully lessening the resistance of sheet ice to downstream moving ice floes.

On 7 Feb 2022, NYS Canals tweeted “We believe our proactive icebreaking efforts will help mitigate the ice & high-water challenges that Schenectady and other Mohawk Valley communities face each winter, but...It’s important to remember that despite the icebreaking efforts, ice jams are still possible!” And then a statement about the overall ice-breaking project: “We are doing research and collecting data about how icebreaking can increase Mohawk River resiliency of the greater Schenectady area. Nearby residents should remain vigilant and monitor conditions in their area.”

Brian Stratton, Director of NY Canal Corp, noted in a video message: “The Canal corporation launched a pilot program to try to reduce the threat of ice jams and the flooding that follows. It starts with the deployment of these tug boats here on the Erie Canal and the Mohawk River. These expanded ice breaking efforts are being performed in anticipation of increased river flows and ice movement to minimize the potential for ice jam formation in the Schenectady area.”

So the message here is that we will still probably have ice jams but this effort will hopefully lessen the impact of ice jams and reduce flooding. But we are prepared for ice jams and the resulting flooding that may occur.

If you want to stay informed about ice jams, and track developments and warnings when the weather warms, there are two outlets on social media that you can turn to. One is the Mohawk Watershed Alliance Facebook page and the other is the Mohawk Watershed Twitter feed. Both will be updated frequently, especially at that critical time during breakup when the situation can change quickly. Finally recall that you can access the USGS Jam cam and ice monitoring page for live video and plots of river levels.

This and other Notes from a Watershed are available at: Mohawk.substack.com

Further Reading

[1] Reimagine the Canals Task Force Report. January 2020. Available here.

[2] Ice Jam mitigation panel report to the Reimagine the Canals Task Force. Released January 2020 (Available here).

[3] Garver, J.I., 2019. The 2019 mid-winter ice jam event on the lower Mohawk River, New York. In: Garver, J.I., Smith, J.A., and Rodak, C. 2019. Proceedings of the 2019 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March 22, 2019, Volume 11, p. 12-17. (Download paper here).

[4] Garver, J.I., 2018. Ice Jam flooding on the lower Mohawk River and the 2018 mid-winter ice jam event. In: Cockburn, J.M.H. and Garver, J.I., Proceedings from the 2018 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady NY, 23 March 2018, v. 10, p. 13-18. (Download paper here).

[5] Garver, J.I., Capovani, E., and Pokrzwka D., 2018. Photogrammetric models from UAS mapping and ice thickness estimated of the 2018 mid-winter Ice jam on the Mohawk River, NY, In: Cockburn, J.M.H., and Garver, J.I., Proceedings from the 2018 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady NY, 23 March 2018. p. 19-24. (Download paper here).

[6] Garver, J.I., 2014. Insight from Ice Jams on the Lower Mohawk River, NY. In Mohawk Watershed Symposium 2014. (Download paper here)

[7] Huang, F., Shen, H.T. and Garver, J.I., 2020, March. Numerical modeling of breakup ice dynamics in the lower Mohawk River. In Mohawk Watershed Symposium 2020 (p. 37). (Download paper here).

[8] 14 December 2020. Press release “Governor Cuomo announces new pilot program to improve resiliency along Erie canal and Mohawk River - Pilot Program Will Test Innovative Ice Breaking Methods this Winter as Part Of The Reimagine The Canals Initiative in Schenectady County”