Ice Breakers on the Mohawk

A new strategy aimed at mitigating ice jams in Schenectady

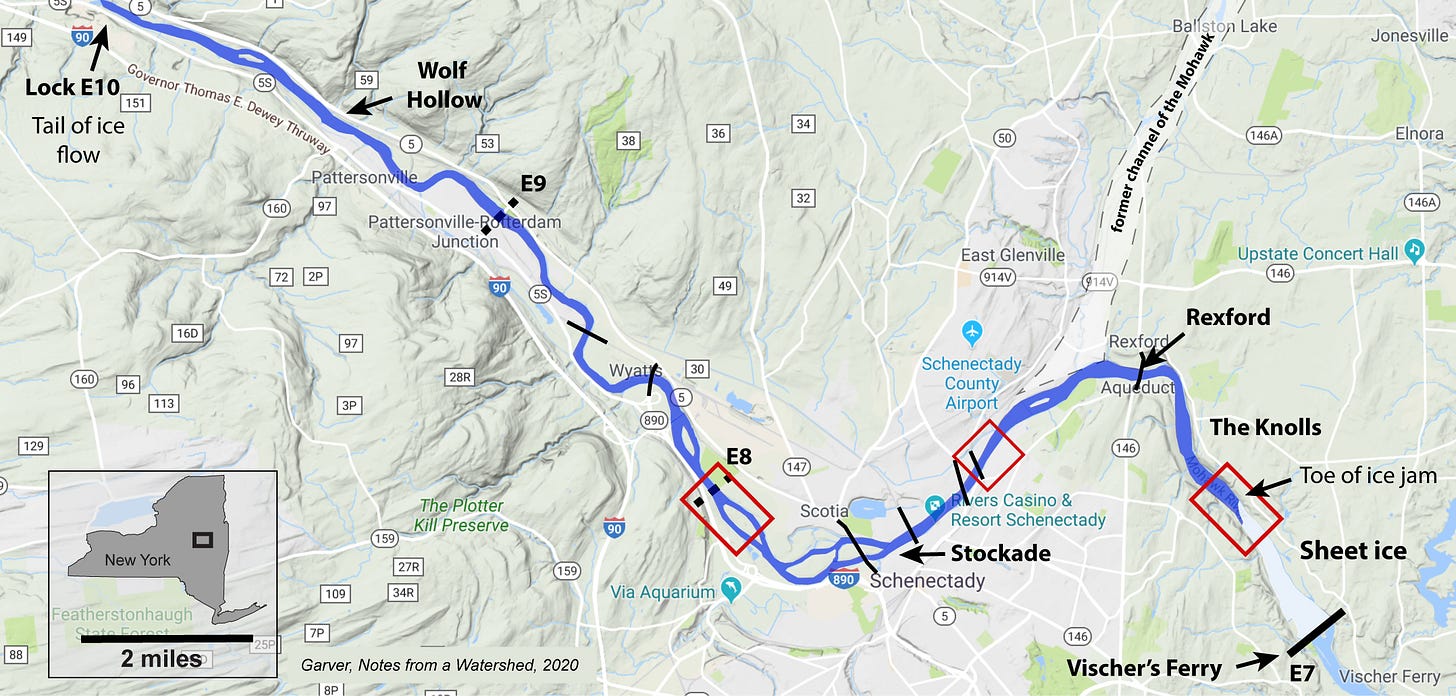

Chronic ice jams on the Mohawk River block the river and cause back-up flooding in local communities including the historic Stockade district of Schenectady. The 2018 ice jam was enormous and threatened communities for over a month, and the event turned the tide on mitigation efforts. In 2019 the Reimagine the Canals task force [1] coordinated with an Ice Jam Mitigation Panel at the NY Power Authority (NYPA) that looked into mitigation strategies for ice jamming on the lower Mohawk River [2]. The Panel focused primarily on the Schenectady pool, a section of the Mohawk between the Vischer Ferry Dam (and Lock E7) and the upstream Lock 8 in Glenville/Rotterdam. This section of the River has known chronic jam points that result in urban flooding, especially in the Stockade. One recommendation from that effort was the use ice breakers to break sheet ice upriver from the Vischer Ferry Dam (VFD) and a recent announcement from Governor Cuomo’s office indicates that we may see the first use of tugs to break ice in the winter of 2020-21 [16].

The 2007 ice jam on the Mohawk River backed up water that flooded the historic Stockade district in Schenectady (here Ingersoll Avenue). Can ice breakers alleviate ice jams in this chronically flooded area? (Photo: J.I. Garver).

I have studied ice jamming on the Mohawk since the colossal jam of 1996. Part of that work involves understanding the location of jam points that cause problems, and I have written a number of short papers about recent ice jam events, including the 2019 jam [4], the 2018 jam [5], and many others back to 1996 [see refs in 6]. Recently we did extensive studies on the enormous 27-km long ice jam of 2018, and this included understanding the formation, jam points, and release waves from that event [7]. I recently wrote a Watershed Note about our mapping of the toe area in the Rexford Knolls using drones and photogrammetric mapping, and from this work we developed a model of the ice jam and were able to estimate that the imbricated and thickened ice had thicknesses between 10 and 24 feet [7]. That work provided a critical framework for the next set of studies that were aimed at modeling ice using computer simulations, which were published in March (2020) [8].

Map of the 27-km-long ice jam in the Mohawk River in 2018. Those stretches of the River where ice jamming occurred in this event are in red. The toe of the ice jam was in the Rexford Knolls just upstream from the Vischer Ferry Dam. This is a chronic jam point and one of the primary targets for mitigation because jamming there causes back-up flooding in the Stockade [map modified from 5].

Reimagine Task Force. One facet of the Task Force effort was aimed at understanding ice jams and ice jam flooding in the lower part of the Mohawk, in particular in the Schenectady pool where ice jamming is chronic and damaging. Ice intervention options can be complicated and they vary dramatically depending on the specific geography of the river, nature of jam points, and tolerance for risk. The Task Force report had specific recommendations that were sent to Governor Cuomo in December 2019, and in January 2020 he announced that $65 m would be directed to ice jam mitigation in the Schenectady area.

In 2019, the Ice Jam Mitigation Panel evaluated nine possible interventions. These included ice booms, dynamite, ice retention, ice breaker and/or cutter, removal of obstructions, dam modification, and channel modification by sediment removal. Several of these were eliminated due to issues with river geometry, flow conditions, or safety. Blowing up the ice was eliminated from consideration, and in the end four primary strategies emerged that address ice in the channel. They included:

Ice breakers or cutters to physically break up ice in hotspot areas.

Obermeyer Spillway Gates on the Vischer Ferry Dam (at Lock E-7) to manage water flows, and potentially “flush out” ice jams.

River channel re-profiling that involves dredging and sediment removal to alleviate choke points.

Removal or modification of bridge abutments and potentially retrofitting existing bridges to help break up ice jams.

The history of ice jam mitigation on the lower Mohawk is littered with stories of exciting and dangerous strategies to break up ice jams. Dynamite was used to break up one of the biggest ice jams on the lower Mohawk in late March 1914 when the jammed ice was dynamited in Crescent, and the force of the explosion rocked nearby houses [9]. On 21 February 1954 an ice jam on the Mohawk in front of the Stockade district was dynamited in an attempt to loosen the ice and get it flowing; the explosions resulted in projectiles of ice chunks that landed in the residential area of Ingersoll Avenue and broke windows and damaged slate roofs [10].

Even more aggressive techniques have been used, but not without problems. An issue, of course, is that when ice jams form, the public puts pressure on officials to address the ice jam to alleviate flooding. Naturally when it comes to ice, we learn a lot from our friends in Canada. In 1951 a major ice jam on the South Saskatchewan River resulted in blockage and flooding in Fort McMurray. The Royal Canadian Air Force was summoned and they initiated Operation Wet Hat, which involved an ice-jam bombing campaign. Local residents next to the jam were asked to evacuate prior to the bombing run. The RCAF first dropped a 1000-pound bomb followed by eight 500-pound bombs; the ice jam did not break up [11]. Once you start bombing runs on the river, you know you have a problem.

Ice jam on the Mohawk in 2018, here in front of the Stockade (Riverside park to the right). This photo was taken on 14 January after the ice jam had lodged downriver in the Rexford Knolls (Photo: JI Garver, 13 January 2018).

Hazard mitigation involves doing things to lessen the impact of a hazard on life and property. We can mitigate ice before breakup, or we can try to deal with the ice jam after it has formed. As a full package, ice jam mitigation in multifaceted: it involves public education and warnings, numerous strategies to reduce back-up flooding in adjacent communities, and then breaking up ice before and after jams occur.

Let’s consider the latter issue, which involves dealing with the actual ice. In a typical winter, ice forms on the river and slowly thickens, which is obviously a function of temperature and a few other variables such as flow rate and snow cover. When warming occurs and discharge increases, we anticipate breakup of ice and ice-out events, which can include ice jams. At this point we go into high alert to monitor and watch for ice jams and flooding. So there are two periods we need to consider: The pre-break up thick ice that has formed in the winter, and the breakup and accumulation of ice in moving streams of ice chunks that may then get jammed. Thus we have a pre-jam condition and a syn-jam condition. The stories of dynamite and RCAF bombing are mitigation for syn-jam conditions: breakup has occurred and ice jams have formed and it's a complicated and intense period of assessment and evaluation by emergency managers. Bear in mind that breaking an already formed ice jam that is blocking water is dangerous because this typically occurs during flood stage and there is considerable pressure on the ice. This is not what ice breakers are for: these conditions are simply too dangerous for on-ice maneuvers.

You can imagine that we can get ahead of the hazard if we can use mitigation strategies that keep ice jams from forming in the first place – pre-jam mitigation. The Ice Jam Mitigation Panel looked into all mitigation options, but focused considerable attention on pre-jam mitigation. The overall strategy is to do things that will keep ice jams from forming in the first place, or at least reduce the size and severity of ice jams. Naturally if we moved everyone off the floodplain we will have much less of a problem, but that is complicated. Although difficult, this is in fact part of what is happening in the Stockade where options are being considered to either elevate homes in place or relocate homes to higher ground [14]. However, even if we were so somehow lift and move all homes off the floodplain, we still have considerable infrastructure that is in or adjacent to the river channel (locks, dams, bridges, etc.). But make no mistake: ice and ice jams are not going away on the Mohawk River. So we need a strategy to reduce their impact. This is where ice breakers come in.

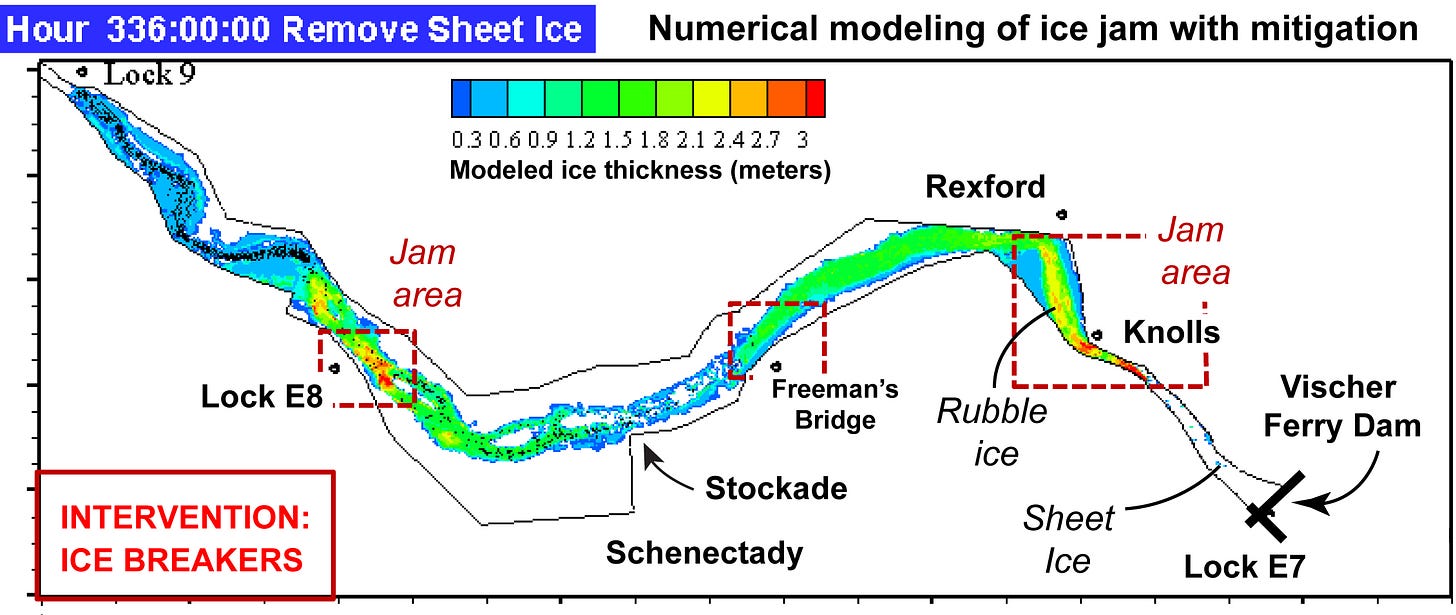

Computer model of ice jams: a game changer. Numerical modeling presented in the Task Force report showed that there was a potential benefit in breaking ice – a pre-jam mitigation strategy – that would lessen the severity and magnitude of ice jam formation at the Rexford Knolls. Based on this finding the committee recommended further study of four potential interventions that may alleviate ice jams in the Schenectady area.

Numerical modeling of ice jams on the Mohawk River. This diagram is modified from the Ice Jam Mitigation Panel Report entitled “Ice Jams in the Mohawk River Valley: Report to the Reimagine the Canals task Force” (Jan 2020 – see Figure 12a). This computer simulation shows that ice jamming will occur even with pre-break-up intervention with ice breakers, but that the ice jam at the Knolls is smaller than without intervention. The numerical modeling in the Task Force report was done by Fengbin Huang and Hung Tao Shen of Clarkson University [see 8].

In that study, the numerical model - a computer simulation of ice floes and ice jams - was used to assess the effectiveness of breaking sheet ice prior to an ice-out event. This means that ice is broken immediately prior to high discharge and natural breakup of sheet ice in a thaw. Historically, we know that in typical break up events we have several-day lead time where the onset of warm weather and possibly rain are forecast.

It is important to underscore that the numerical modeling is a major, historic, and spectacular breakthrough in understanding ice jams on the Mohawk. This pioneering work, done by Fengbin Huang and Hung Tao Shen of Clarkson University, will undoubtedly be a central piece of future ice jam mitigation strategies. For the first time ever, the dynamics of ice in this part of the Mohawk can be visualized and manipulated with a computer model and that model can be used as a “tool for studying the breakup ice jams in the Lower Mohawk River and assist the design of ice jam flood mitigation methods” [8].

That modeling, which first appeared in the Task Force report in January 2020, showed two things relevant to breaking ice upstream from the VFD in the Schenectady pool. The models showed that with the use of ice breakers: “There are significant improvements at Rexford / Knolls, as major segments of the ice jam break up earlier, allowing the Mohawk to flow past the bend in the river... [and] There are improvements at the Vischer Ferry Dam pool, which sees its sheet ice flushed out of the pool and over the dam crest” [see 2, p.19].

The Vischer Ferry Dam. The role that the Vischer Ferry Dam plays in ice jam formation has been a heated topic for about a decade. Jim Duggan, a former resident of the Stockade and retired architect, has worked doggedly to understand the relationship between the VFD, ice jam formation, and Stockade flooding. He has made significant progress. The announcement by Governor Cuomo last January of plans to address ice jamming was well received: Jim was “quite pleased” with the announcement that the situation will finally be addressed [15].

Another facet of the Task Force effort was an evaluation of flooding across the entire Mohawk and overall strategies to reduce flooding. This is relevant here because that study also considered the role that the VFD plays in flooding or the role a modified dam may play in reducing flooding. The Mohawk Flood Assessment (MFA), done by Bergmann and Associates and lead by Ken Avery, looked at ways to reduce flood damage by evaluating the benefits of mitigation options and the cost of those options [12].

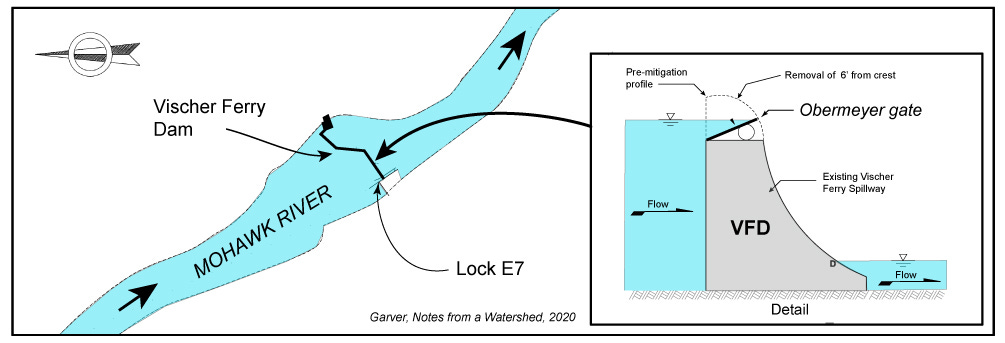

One mitigation option evaluated by the MFA is lowering of part of the crest of the VFD. The installation of Obermeyer gates (a crest gate with pneumatic lifts) would allow the dam crest to be lowered by six feet in the event of flooding. Those options have been presented [see 12, and 13], but not yet evaluated in the context of ice and ice jamming, but the MFA report to the Task Force noted that “This intervention would also have potential benefits to mitigate flooding caused by ice jamming.” [see 12, p. 18]. This is an important point, but we need to wait and see how that evaluation progresses.

The Bergmann Mohawk Flood study [12] suggested that lowering the crest of the Vischer Ferry dam (VFD) by six feet may provide a mechanism to control flood waters and indicated that the lower crest may also play a role in ice jam mitigation. The installation of an Obermeyer gate may allow reduction of the dam crest [modified from 12, their figure 1 of Appendix D].

Ice Breakers. Ice jams in the Schenectady pool are caused, in part, by the permanent VFD. The Schenectady pool is nearly static, and as a result significant sheet ice builds during the winter. But it also has a low gradient (nearly flat), so faster moving water from up river encounters this slow moving static pool and that causes large-scale slowing of the ice trying to get down the river [7]. Thus, this is where problems occur. Add a final twist with the naturally narrow channel or constriction in the Rexford Knolls (inherited from late-glacial river incision) and everything conspires to form a chronic ice jam point [I more fully discuss this in 7].

The location of this permanent dam is critical in understanding ice jam flooding on the lower Mohawk. On the main stem of the Mohawk, every dam upstream of the VFD is removable, and these removable dams get lifted out of the water in the winter, specifically because of the ice hazard. Thus during breakup events all the upstream ice flows downriver, but it tends to get caught in the pool in front of the VFD. It is this pool where the ice breakers are moored.

Two tugs, which will be used to break ice, are owned by the NY State Marine Highway Transportation Company of Troy. They are prepositioned at Lock E7, just above the Vischer Ferry Dam in the Schenectady Pool. The larger (right) is the steel hulled Margot (see the specifications and history of this boat here) and smaller is the Benjamin Elliot (Photo: David Truland, 4 December 2020. Used with permission. See this and other photos here).

Relief from ice jamming in the Schenectady area was one of the central pieces of the Reimagine the Canals effort, and ice jam mitigation was part of the first phase of funding announced by Governor Cuomo in January 2020.

View of the Margot moored above lock E7 in the Schenectady pool. Ready for freeze up. (Photo used with permission: J. Kalohn, Dec 2020).

The announcement was welcome news. Assemblyman Phil Steck (NY 110, which includes Schenectady and the Stockade) has been outspoken advocate for flood relief and ice jam mitigation. He said in a statement: "My constituents have been seeking a solution to the problem of ice-jam flooding in the Mohawk River since I first entered The Assembly in 2013. The Governor, Canal Corporation, and NYPA have responded by studying the issue and now putting the results of those studies into action. On behalf of my constituents, we are most grateful for their efforts. While this pilot program is exciting, flooding in the Mohawk River is a complex problem which may require additional work in the future, such as corrections to the Lock 7 dam.” Corrections in this context means lowering the crest by the method explored above.

The plans just announced by Governor Cuomo to mitigate ice jamming on the lower Mohawk River are an important first step in mitigating ice jams on the lower Mohawk River. The goal of these efforts is to break ice up and move ice more efficiently through the channel, especially in the problematic area between the Rexford Knolls and the VFD. If these plans are successful, there may well be a reduction in back-up flooding due to ice jams in Rexford, the lower parts of Scotia and Glenville, and in the Stockade neighborhood of Schenectady. However, efforts to break ice will not stop flooding in the Stockade, and therefore the ongoing efforts of the Stockade Flood Mitigation Project [14] should proceed because flood mitigation will remain a critically important step for that community.

This and other Notes from a Watershed are available at: https://mohawk.substack.com/

Further reading

[1] Reimagine the Canals Task Force Report. January 2020. Available here.

[2] Ice Jam mitigation panel report to the Reimagine the Canals Task Force. Released January 2020 (Available here).

[4] Garver, J.I., 2019. The 2019 mid-winter ice jam event on the lower Mohawk River, New York. In: Garver, J.I., Smith, J.A., and Rodak, C. 2019. Proceedings of the 2019 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March 22, 2019, Volume 11, p. 12-17. (Download paper here).

[5] Garver, J.I., 2018. Ice Jam flooding on the lower Mohawk River and the 2018 mid-winter ice jam event. In: Cockburn, J.M.H. and Garver, J.I., Proceedings from the 2018 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady NY, 23 March 2018, v. 10, p. 13-18. (Download paper here).

[6] Garver, J.I., Capovani, E., and Pokrzwka D., 2018. Photogrammetric models from UAS mapping and ice thickness estimated of the 2018 mid-winter Ice jam on the Mohawk River, NY, In: Cockburn, J.M.H., and Garver, J.I., Proceedings from the 2018 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady NY, 23 March 2018. p. 19-24. (Download paper here).

[7] Garver, J.I., 2014. Insight from Ice Jams on the Lower Mohawk River, NY. In Mohawk Watershed Symposium 2014. (Download paper here)

[8] Huang, F., Shen, H.T. and Garver, J.I., 2020, March. Numerical modeling of breakup ice dynamics in the lower Mohawk River. In Mohawk Watershed Symposium 2020 (p. 37). (Download paper here).

[9] NY Times, 30 March 1918. Big Ice Gorge Blown – Aqueduct and Canal Locks at Crescent, NY were in Danger. (Access through NY Times time machine)

[10] NY Times, 22 February 1954. Ice Jam Dynamited – Chunks fall into residential area of Schenectady. (Access through NY Times time machine)

[11] Slade, Gillian. 1 May 2020. Advice from Hatters to Fort Mac: Don’t Bomb the ice Jam. Medicine Hat News. Read that article here.

[12] Bergmann Task Force report on Flooding. Avery, K., and colleagues. Released Jan 2020. Mohawk Flood Assessment Report. 105 pages.

[13] Avery, K., and Juza, B., 2020. Reimagining the Erie Canal/Mohawk River as flood risk mitigation resource. In. Garver, JI., Smith, JA, and Rodak, C., 2020 Proceedings of the 2020 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady NY, March 20, 2020, v.12, p. 1-8 (paper in Abstract volume here).

[14] Irwin, M., 2020. Stockade Resilience: Feasibility analysis of flood mitigation alternatives and design of mitigation measures to protect Schenectady’s Stockade Neighborhood In Garver, J.I., Smith, J.A., and Rodak, C. 2019. Proceedings of the 2019 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March 22, 2019, Volume 11, p. 27-32. (paper in Abstract volume here).

[15] Foss, Sarah. 11 January 2020. Foss: State plan for Lock 7 dam at Niskayuna a breakthrough. Daily Gazette. (Article here).

[16] 14 December 2020. Press release “Governor Cuomo announces new pilot program to improve resiliency along Erie canal and Mohawk River - Pilot Program Will Test Innovative Ice Breaking Methods this Winter as Part Of The Reimagine The Canals Initiative in Schenectady County”

Great article John. I would agree that bombing is indicative of a problem...