A Stockade Solution

A hybrid plan to Retreat and Elevate may serve as a national model for flood mitigation in historic communities

Inundation from Hurricane Irene in 2011 was a catalyst for what has been a decade-long process for flood mitigation in historic Stockade district of Schenectady (NY). The first phase of an $8 million FEMA-funded project was initiated in 2018, and it is aimed at flood mitigation and building resilience into the community. The mitigation effort has been complicated and it has evolved slowly over a decade; the early history is covered in the first Stockade Watershed note here [1]. That history involved ideas as radical as moving all houses off the flood plain, or elevating all homes in place. Elevating a single home in 2017 was a important step in this process because it highlighted issues of historic preservation and the technical challenges of moving centuries-old houses [1]. Moving forward it appears that a hybrid approach will be used, and – if all goes forward - the first houses to be mitigated are those deepest on the floodplain. Once that move is accomplished, space will be created for subsequent phases of the plan.

Funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) aimed at flood mitigation started in 2018 when the first phase of the FEMA-funded project started with a community meeting. For the first time the City and local residents could see a realistic and exciting plan starting to crystallize. This phase of funding is focused on finding a solution, and with FEMA’s approval, the second phase would be funded, which is the implementation phase. But the pandemic got in the way and now a concern is whether there is the momentum and energy to moved this important ambitious and historic plan forward.

Map of part of the Stockade shows the floodplain and the focus of flood-mitigation efforts. This is part of the oldest section of the city of Schenectady, which has been continuously inhabited for over 350 years. Purple is the FEMA-mapped area with a 1% chance of annual inundation (“100 year floodplain”), and the turquoise is the area with a 0.2% annual inundation probability. Map modified from FEMA flood mapper, here.

My last post, which is a companion to this effort, covered the last decade of ideas about saving the Stockade from flooding [01]. There is an emerging consensus is that the mitigation solution needs to preserve historic architecture and streetscapes, and thus any solution is bound to be complicated. As we get closer to a solution, one other thing becomes clear: a hybrid solution is probable given the complexity of neighborhoods and the different types of structures on the floodplain.

The Stockade effort is a nationally significant undertaking and if it is successful, communities around the country will look to Schenectady for inspiration and guidance. Flood mitigation and building resiliency in historic areas is complicated because wholesale relocation is not possible and demolition is off the table.

The historical significance of the Stockade cannot be understated [02,03]. Settled by the Dutch in 1661, the Stockade is one of the oldest occupied neighborhoods in the United States. The US National Park Service has described the Stockade as "the highest concentration of historic period homes in the country," with over 40 houses older than 200 years [03]. Thus these mitigation solutions are partly aimed at preserving our national heritage.

FEMA funding for an integrated flood mitigation plan

In 2016, the City applied for FEMA funding for pre-disaster mitigation for homes on the floodplain in the Stockade. We can be assured that FEMA was (and is) interested in a broad long-term solution because they have paid out repeatedly for flood damage claims. This $8.6 m plan follows a two-pronged approach: first study the options, and then implement a solution – a similar approach to what was in the 2014 NY Rising plan [04, 05]. In September 2017 there were pressing national needs associated with Hurricane damage from Irma and Harvey, and thus FEMA delayed funding and decisions for long-term mitigation projects [06]. An RFP from the City for a flood mitigation plan was released in June 2018 with proposals due in July 2018 [07]. At the time the City had hired Margaret Irwin, Principal of River Street Planning and Development, to guide all project management services related to the proposal. The RFP called for all work for Phase 1 to be completed in one year (fall 2018 to fall 2019).

In the fall of 2018, the City of Schenectady announced that it had been awarded a FEMA grant through the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program through the NY Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Services (DHSES) to determine the best path forward with flood mitigation in the Stockade [08]. The City retained River Street Planning and Development (“River Street”) to lead the project along with Mesick Cohen Wilson Baker Architects, Place Alliance, and several other firms.

Kristin Diotte is the director of Development for the City of Schenectady and she has been a key player in moving this effort forward. She has a long-standing interest in climate change and building resilience into the City. In the initial press release about the FEMA funding she noted: “It has become a priority to address the Stockade Historic District's vulnerability to the longstanding issue of flooding which involves a diverse range of stakeholders. City staff and the design team that has been assembled are dedicated to working with residents in arriving at a comprehensive solution that will protect and preserve the character of this historic neighborhood for a resilient future.” [08]

She later wrote that the approach would include moving properties out of the floodplain. “It is a strategy we are referring to as 'adaptive preservation,' which allows for climate adaptation by relocating historic buildings out of floodplain while preserving their character, relationship to the street and ultimately the vibrancy of the Stockade” [09]. So it is wonderful to see that the City has a vision and a plan.

Mayor McCarthy, interviewed by WAMC in 2018, emphasized the importance of maintaining the historical character of the Stockade: “By virtue of it being a historic district, you want to maintain the integrity and character that exists there” [10]. This means preserving houses, but this approach may come at a considerable cost.

River Street and partners held the first public meeting for Phase 1 with Stockade residents and other interested stakeholders on 23 October 2018 [10]. This phase of the project, which was to continue through 2019, involved conducting a Comprehensive Mitigation Analysis to assess existing conditions, evaluate alternatives, and recommend a preferred mitigation solution to FEMA [11]. Phase 2, contingent on success of Phase 1, involves implementation of the approved plan.

2019 Charrettes in the Stockade: Mitigation options

One of the first public presentations of the emerging plan was at the Mohawk Watershed Symposium in March 2019 by Margaret Irwin of River Street. In her talk she explained that the project was going to be executed in two phases [11]. Phase 1, funded at $1.2 m, was the initial study and was to be completed by June 2020. Phase 2, with anticipated funding of $7.545 m, was the implementation phase and would be underway only after a successful Phase 1. At the time, the plan involved 56 single and multi-family houses that met the criteria for eligibility by being both on the floodplain and in the Stockade Historic District [see also 11].

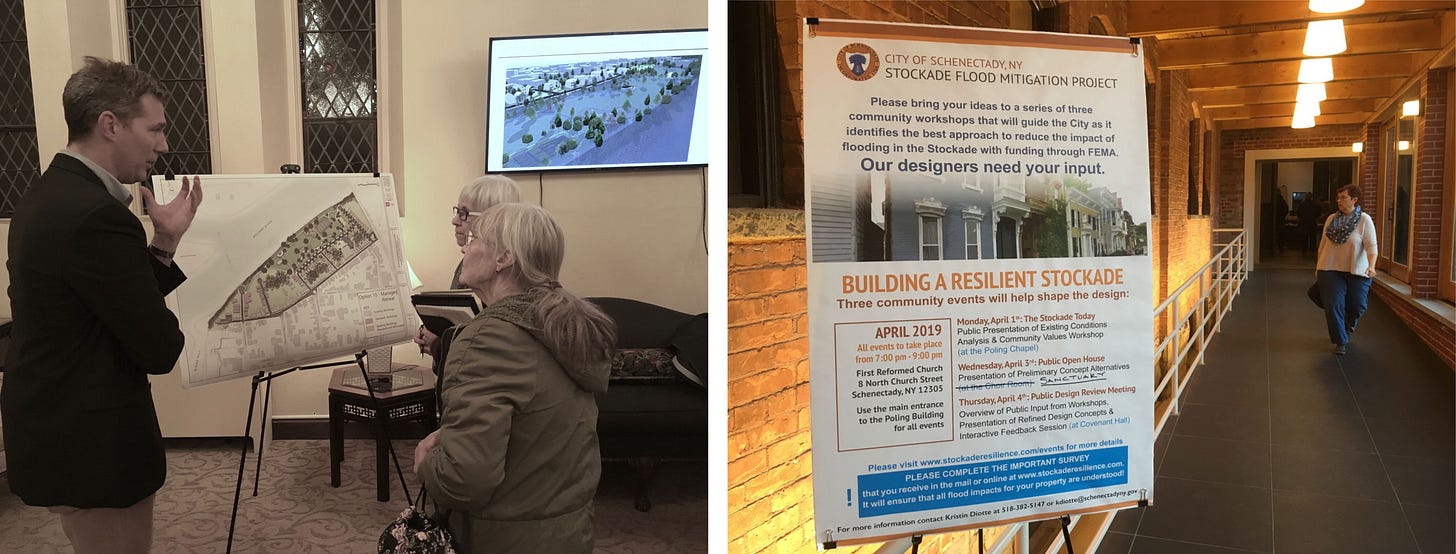

The real rollout of the planning process occurred in three meetings held in early April 2019 at the First Reformed Church in the Stockade. It was in these three days of meetings that the options were laid out and decisions were made about the project direction based on feedback from residents and others.

The April 2019 meetings were an important and significant step forward in the historical timeline of flood mitigation in Schenectady. Residents and the City were involved in an exchange of ideas and evaluated potential solutions that were bold, dramatic, and certain to have far-reaching effects on the Stockade. The meetings occurred over three nights and there was a well-organized progression and flow from beginning to end. I went to all three meetings because I was interested in seeing how the process unfolded and I am interested in flood mitigation.

The April 2019 meetings included charrettes with the different mitigation scenarios. The photo on the left shows Ian Law, Principal at PLACE Alliance Northeast, explaining the Retreat option where much of the focus is on moving houses on Ingersoll Ave to the high ground of the plateau. To the right is the poster for the sessions with Carol DeLaMarter, former president of the Stockade Association. Photos: JI Garver.

The first night (1 April) was the public presentation of existing conditions, analysis, and community values workshop [12]. Here we learned about ice jams, free-water floods, the basic issues of the Base Flood Elevation (BFE), and how the community has been affected by flooding. We also learned that work by James Woidt, then of Shumaker Consulting Engineering, revealed that the FEMA-determined Base Flood Elevation (or BFE) in the Stockade was too low because it failed to take into account ice jam flooding, which dominates flood events in the Stockade. This finding meant that the effective (or newly proposed BFE) was actually higher, 232’ up from 230’ – but this change would need to be approved by FEMA (determination is still pending – the map at the beginning of this post is 230’). Nonetheless, the two-foot increase in the BFE means that there are 75 homes – not 56 - on the floodplain and in the special flood hazard area. The Design Flood Elevation (DFE), would now be 234’.

The goal in this effort is to keep people safe and to protect property. The consulting team and local residents identified key values that would help guide the project. In this first evening session stakeholders were asked to rate what values were most important and what values were less important. Attendees evaluated five values: a) Views of the River; b) Access and utilization of Riverside Park; c) Historic preservation of architecture; d) Preservation of neighborhood fabric; and e) Long-term resilience. In this exercise participants rated each with a 1 (highest priority) to a 5 (lowest priority) – each person had five stickers and had to rank all five values from 1 to 5 [12].

The results of this exercise were posted at the project website. I recalculated the scores from the Values exercise using a weighting scheme that accounts not only for top vote getters, but also for those values that were middle-ranked and low-ranked. Of the five options, the value with the lowest score and therefore the highest priority was Historic preservation of architecture (score: 62) followed closely by Preservation of the neighborhood fabric and Building resilience (score for both: 65). The two lowest-ranking values were Access and utilization of Riverside Park (score: 76) and Views of the river (score: 87). Obviously these results may be biased because they are a sample of individuals who chose to show up to a meeting on building Stockade resilience, but nonetheless it seems clear that architectural preservation is important to many people in the Stockade, so flood mitigation should make this a central consideration.

The second night (3 April) was a presentation of the preliminary concept alternatives that were numbered 1-10 [12]. The first three involved river-specific options that would not be funded by FEMA, so we were left with Options 4-10. These flood mitigation options were: 4) Levee; 5) Wall; 6) Wall with private development; 7) Elevate; 8) Elevate with raised streets; 9) Elevate and relocate; and 10) Managed retreat. As you can see there is some overlap between options, and we can really boil these down to three basic ideas in increasing complexity and level of disturbance: a) Add a barrier, keep water out, but impair green space; b) Elevate homes and perhaps streets in place and let water come in; c) Move some or many home and elevate where its easiest to elevate and expand green space. The last option is most disruptive, but potentially the most effective because all homes are removed from the floodplain. The first option is least disruptive and has the potential to be an ideal solution for historic preservation because no homes need to be elevated nor moved.

The third night (4 April) was the public design review meeting where refined concepts were presented and the public gave feedback, in part during project-specific charrettes [12]. This last night was the most interesting and exciting because everyone participated and ideas had matured. In the beginning of the evening we were reminded of the progression of the 3-day process: 1) what is the flood problem; 2) what are possible solutions; and 3) what do we do?

The options were presented and there were seven stations where each option was presented and discussed. People moved from option to option to learn the details and discuss issues. Everyone was then given three stickers with #1, #2, and #3 to rank their top three choices. By the end of the evening the Managed Retreat option had received the most #1 stickers, followed by the Levee option: these are the yin and yang of flood mitigation options.

The Flood Mitigation Option Board with participant choices at the end of the evening on 4 April 2019 after the design charrette. Stickers with #1 choice are here circled in red (#3 in blue, and #2 green). By the end of the evening the top #1 choice was Managed Retreat, and then the Levee. Modified from a photo by JI Garver.

At this point it was up to the consulting team to work up costs, benefits, and logistics of the favored option and to then present this to FEMA by the beginning of 2020, and then this first phase would be completed by June 2020. Much of the energy and time was put into determining what a managed retreat would look like, and in any retreat scenario Ingersoll Avenue had to be front and center because it has the most houses that were located deep in the floodplain (low elevation and closest to the River). But recall that a common theme and important value was preservation and maintaining the historic integrity of the district.

2020-21 Pandemic

As we all know, when the pandemic hit NY in mid-March 2020, many things got derailed, including this flood-mitigation project. But as the pandemic dragged on, there was concern that the project might lose all of its momentum. For me the pandemic meant teaching Natural Disasters online, and a key module in that course is focused on flood mitigation in the Stockade. The Mohawk Watershed Symposium was scheduled for March, but was cancelled. Here we were supposed learn of the updated plan.

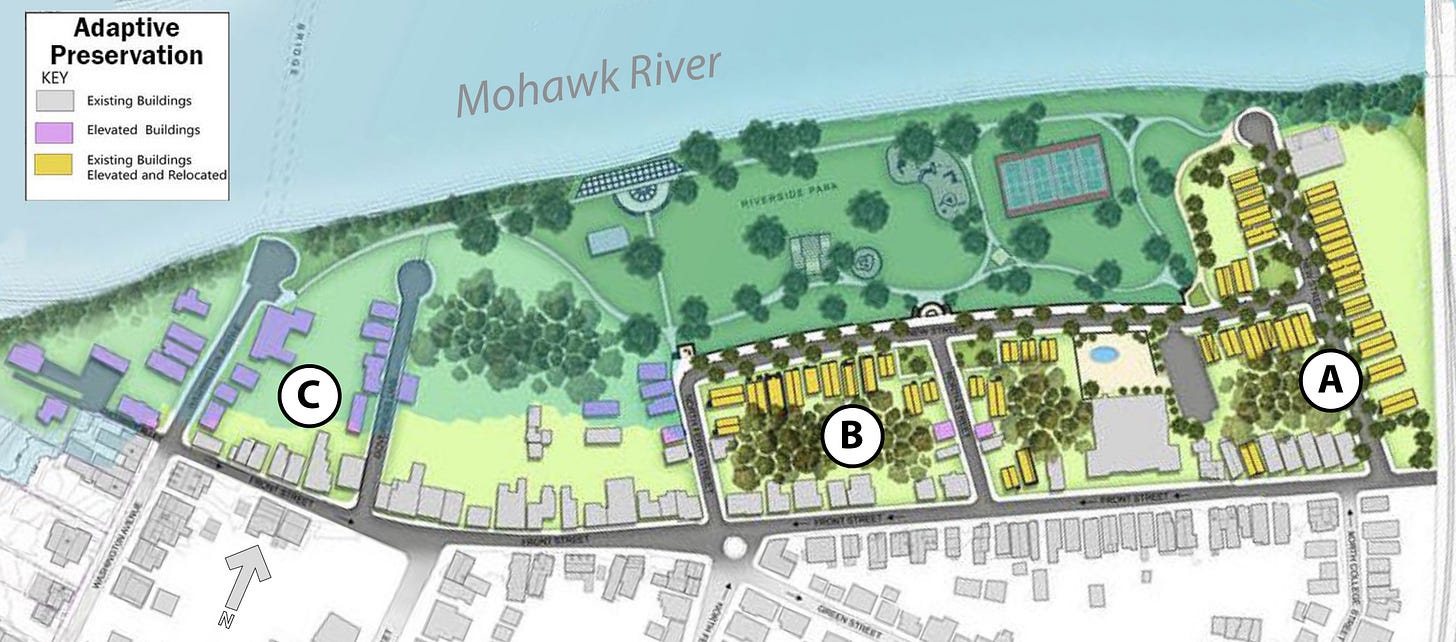

The hybrid Managed retreat and Elevate plan that was to be presented at the Mohawk Watershed Symposium in March 2020. Buildings in Yellow are moved to what would be higher ground, buildings in pink would be elevated in place. Gray buildings are above the BFE. The plan has three primary elements (A,B,C) and A must occur first. Both A and B occur on elevated land. This figure is modified from Diotte 2020 [09]. Details of the right side of this diagram are explored in the next figure.

In May 2020 I talked to Ian Law at Place Alliance to get an update on the mitigation effort. In this first conversation, he told me that FEMA has typically has two primary mitigation approaches that they like to explore first: one is buyout and demolition; and the other is elevation [raising houses]. Because the homes in the Stockade are historic, buyout and demolition, which is used across the country (and even in the Mohawk Watershed) is not an option. So we need to consider elevation or something more radical like moving homes. Because many of the homes would have to be raised so much (8-10 ft) a fix by elevating the house would require 20 stairs or more, which obviously impairs the livability of the home.

Ian told me that the effort had made tremendous progress since 2019 and an emerging plan involved moving houses on Ingersoll Avenue as a key first phase of what would now be a more protracted effort that is likely to extend past the initial idea to first study and evaluate, and then to implement a full plan for all homes on the flood plain. It is now looking more likely that the mitigation effort will first focus on relocating houses on Ingersoll Avenue to higher ground on what is referred to as the Plateau (see diagram). Let’s call this the Ingersoll Retreat. This plan essentially means moving all 21 homes on one block and retaining all adjacencies. The move would solve a critical piece of the mitigation puzzle by taking care of the largest number of adjacent homes on the floodplain. The plan would leave the remaining houses (in B and C), for now.

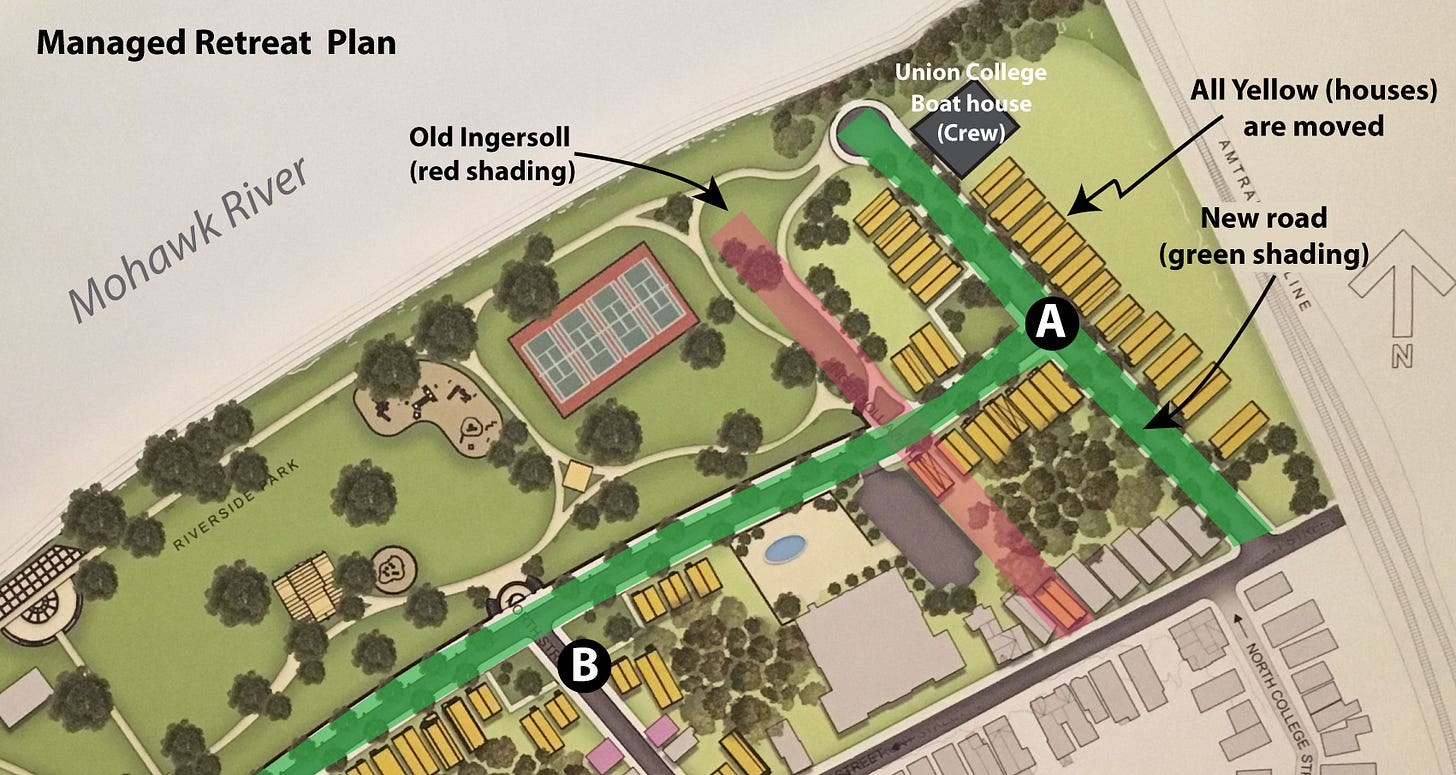

This early map shows a rendering of the Ingersoll Ave and North St parts of the Stockade. In this iteration, all yellow houses have been moved, and pink houses have been elevated in place. This version of the retreat plan was from April 2019, and the plan has since changed. However, an important aspect of this plan is that the entire Ingersoll move (A) has to occur first (to the “plateau”), and only then can the reconfiguration happen on North St and elsewhere (B). The position of the old Ingersoll Ave is shaded red. In latter versions of this plan the Union College Boathouse is removed and that space is used for more houses.

Natural Disasters meet the City

Let’s pause for a minute so I can tell you how I approach this problem with my students. For nearly two decades I have taught a course in Natural Disasters at Union College in Schenectady NY. Since I designed the course, students have had projects that address flooding and ice-jamming, and the effect of flooding in the Stockade. In the last two years I have expanded the focus on Mohawk flooding in a module I call “Stockade Solutions.” In this module, students learn about mitigation options, and then present the advantages and disadvantages of five alternative scenarios. These are not all mitigation scenarios, but mitigation is the theme. They are: a) Build a levee and keep water out; b) Elevate homes and streets in place; c) Retreat and move as many homes to a new location; d) Fix the river so it does not flood (or reduce flooding); e) Leave it the way it is (do nothing) and let residents fend for themselves. The final option - to do nothing – is certainly the easiest, and it effectively puts mitigation entirely in the hands of individual homeowners. This approach would result in a complicated mix of solutions including raising homes, purchasing flood insurance, and perhaps even house abandonment.

In class, we spend considerable time going over the background science of climate change, hydrology of the watershed, historic floods, and how ice jams pose a unique and challenging hazard in the Schenectady Pool of the Mohawk River. We also talk about how FEMA prefers to approach problems, and issues related to historic preservation. But the highlight of the module is interviews with local residents, scientists, and urban planners (please contact me if you are interested in participating). It is from these interviews that students get to see a divergence of opinions. Some students argue that managed retreat is the only real solution for the long-term flood mitigation and preservation of homes. Others argue that if preserving homes and the fabric of the historic neighborhoods is a central value, then a levee is the single best option because no one has to move, but that may include sacrifice part of Riverside Park (where the levee would be built).

Why don’t we just fix the river and keep it from flooding? This is a logical question that many ask, and students are especially interested in this facet of the problem. The answer is complicated and deserving of a separate post with a full analysis. The Stockade experiences two types of flooding and inundation from the Mohawk River: free-water floods and ice-jam floods [13, 14]. Free-water floods, like what happened in Hurricane Irene in 2011, tend to be driven by extra-tropical storms, and stalled frontal systems. In these events, significant rain results in lots of water and flooding. There is considerable evidence that the occurrence and severity of these events is increasing [15]. Ice-jam flooding is driven by accumulated ice during breakup that can be thick enough that it actually impairs river flow, thus causing backup and flooding. The majority of floods in the Stockade are caused by backup-flooding due to ice jams [13].

There are two main reasons that ice jams affect the Stockade. Part of the ice jam problem is due to the Vischer Ferry dam, just downstream, which is one of the few permanent dams on the lower Mohawk [16]. The pool of water in front of the dam impairs the flow of sheet ice and rubble ice from upriver, thus causing jams to form upstream from the dam [13]. Plans are underway to address these ice jams, as I recently wrote about here [17]. However it will be nearly impossible to eliminate ice jams from this stretch of the river because of a topographic fluke we inherited from the end of the Ice Age: the narrow, sharply-curved gorge of the Rexford Knolls, carved in the waning stage of deglaciation [13], acts as a natural constriction point in the River. The permanent bottleneck at Rexford Knolls traps and thickens ice floes as they move down the River during break up. So efforts underway now are designed to lessen the impact of ice jams – and also flooding caused by them – but they will not eliminate the hazard completely because the River will remain narrow in the critical spot just downstream from the Stockade. To a certain extent we are stuck with this problem.

What about doing nothing? We may end up here, but let’s hope not. In my opinion this would be an epic failure given how far we have come. In this scenario all homeowners have to deal with flooding on their own. But there are some hidden dangers that are worth considering if we end up going down this road. One of the interviews that helped my students navigate the problem was with Bill Nechamen, who was the State Floodplain Management Coordinator for the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) for over 20 years. He made some important points about the anticipated rising costs of flood insurance and how repeated floods damage houses, which may force demolition. His comments and ideas resonated with the students.

Damage to houses is serious and subtle because it is not immediately apparent. Three experts I talked to emphasized that repeated flooding typically results in decay and degradation of foundations and sill plates. In older historic buildings, timber sills make up the critical interface between a brick or stone foundation and the overlying wall framing and joists. Repeated wetting and drying due to flooding results in rot and decay, and repairs can be extremely costly. Margaret Irwin told me that FEMA-funded mitigation (i.e., elevate or move) requires that buildings are rebuilt as if new, and this would be a critical lifeline for a number of homes in the Stockade with impaired or partly impaired sill plates (especially timber/wood sills) and foundation issues. Here is the subtle danger if nothing is done: some houses may require repairs that are so expensive that demolition or abandonment become probable. Thus if you are interested in historic preservation, the do-nothing path is important to avoid because if decay takes root, house values in the entire district may fall.

A number of students wrote strong statements against doing nothing. One student, Leo Minami, wrote: “As flood insurance gets more expensive people, will be priced out of the neighborhood. Repeated flooding to the historic properties in the Stockade could lead to extensive damage. Both of these scenarios could lead to decay and blight in the area and could damage the integrity of the neighborhood... If nothing is done, the Stockade will continue to experience damaging flooding, which will cause blight and ruin the character of the neighborhood in the long run.”

Current Flood Mitigation status

The Pandemic appears to have derailed this mitigation effort, and it is time we get the effort back on track. When I started digging into this story in late 2020, I was surprised to find that the main website for the effort was offline (Stockaderelilience.com). I kept trying to access the site through the late fall, but had the same result: no such domain. Finally I called Margaret Irwin in late December (2020) and we talked about a number of issues, and the Stockade Resilience web site was one of them. She told me that she thought it had been taken down (or that the domain had expired). She also told me that the contract with her company has expired, and River Street was no longer on the project. Thus, from this perspective, the project seems to be in jeopardy. I started to worry that all this hard work might be for nothing.

In January 2021 I had a productive talk with Ian Law, from Place Alliance. Ian is directly involved in moving this project forward through the murky waters caused by the pandemic. Ian was upbeat and forward-thinking, but he warned that the FEMA extended the deadline to June 2021 (from June 2020), and that the clock is ticking.

I asked Ian if mitigation efforts like this have been done in other historic areas in the US. He said that this district was distinct and unique, and that FEMA appears to be very interested because this has never been done before in a historic district. This is one reason the project is so important.

Ian explained that the plan is now largely focused on the Ingersoll Retreat, and current thinking is that this is the critical first step in a more complicated multi-phased plan. I suspect that the details of this plan will emerge shortly, but it seems as if a primary focus is to move houses on Ingersoll to the Plateau – a slightly higher area immediately to the north (see map above). This step would take care of some of the most vulnerable houses, and it would free up space for subsequent efforts. In a sense this is like a giant game of chess: the movement of pieces depends on what is on the board, and there clearly has to be a strategy to make it all work.

It would appear that homeowners on Ingersoll are very interested in this plan. Any effort like this requires full voluntary participation, and eminent domain is not an option. It was remarkable to discover that 90% of property owners on Ingersoll understand what retreat means (moving their house), and have agreed to continue with the process. This number is significant: owners obviously recognize the importance of flood mitigation and presumably the benefit they get from increasing the structural integrity of homes and also reducing flood insurance rates, which are slated to increase sharply in the next few years.

There is, however, a catch that may hold up this plan. In order for the Ingersoll Retreat to work, property on the plateau owned by Union College needs to be acquired by the City for the effort. Land ownership on the plateau is in two primary parcels: one owned by the City (parking and pool) and one owned by Union College. The College property is the site of the Union College Crew facility, which is the home of men’s and woman’s crew, which is NCAA DIII varsity sport. Occupation of this site by the Ingersoll Retreat would require Union to find an alternate site with direct River access for these teams and the facility. This may be an important opportunity for the College because it might involve a new facility and more direct engagement with the River. This new facility would certainly involve crew teams, but perhaps it could also involve new educational opportunities focused on water quality, ecology, and hydrology. But given the financial downdraft associated with the Pandemic, the College may not be in a position to facilitate such a move.

Next steps

We are at a critical point in this effort. Only time will tell whether we can capture the momentum and not lose our last best chance at mitigating flooding in the Stockade - whatever the plan ends up looking like. It is time for the City, residents, and other interested stakeholders to re-engage in this important process that may well be a national model for flood mitigation in a historic district.

This and other Notes from a Watershed are available at: https://mohawk.substack.com/

Further Reading

[01] Garver, JI. 2021. Saving the Stockade from flooding: Approach to flood mitigation in a historic district in upstate NY: 2011-2018. “Notes from a Watershed” at: Mohawk.substack.com

[02] The Stockade Association. Website here.

[03] Wikipedia entry for the Stockade - Here.

[04] NY Rising – Schenectady Rotterdam, 2014.

[05] Crowell, SS. 2015. Accomplishments and status of NY Rising. In: Cockburn, J.M.H. and Garver, J.I., Proceedings of the 2015 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March 20, 2015, p.14. (This abstract and all abstracts from the 2015 MWS meeting can be downloaded here).

[06] Williams, S. 19 Sept 2017. Stockade FEMA mitigation funding on hold. Comes in wake of hurricanes Harvey, Irma. Daily Gazette.

[07] Request for proposals (RFP): Stockade historic district flood mitigation design guidelines, City of Schenectady NY Department of Development. January 2017. Document here.

[08] City of Schenectady Press Release, 2 October 2018. Community Meeting Scheduled for Stockade Flood Mitigation project: City will be working with River Street Planning and Development and Mesick Cohen Wilson Baker Architects (available here).

[09] Diotte, CM, 2020. Stockade Resilience: Adaptive preservation of the Mohawk River, Schenectady, New York. In: Garver, J.I., Smith, J.A., and Rodak, C. 2020. Proceedings of the 2020 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March 20, 2020, v. 12, p.14-15 (this abstract, and all abstracts from this meeting can be downloaded here).

[10] Willard, Lucas. 25 October 2018. Schenectady gathering input for Stockade flood mitigation. WAMC (here).

[11] Irwin, M., 2019. Stockade Resilience: Feasibility analysis of flood mitigation alternatives and design of mitigation measures to protect Schenectady’s Stockade Neighborhood. In Garver, J.I., Smith, J.A., and Rodak, C. 2019. Proceedings of the 2019 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March 22, 2019, v. 11, p. 27-32. (This abstract and all abstracts from the 2019 MWS meeting can be downloaded here).

[12] I attended all three workshops, took notes, and participated in discussions. The presentations for each of those sessions were available at StockadeResilience.com, but that web site is no longer active. Some of this information is from those presentations, including a few key figures that showed results and data. Some of this information is from my notes.

[13] Garver, J.I., 2014. Insight from Ice Jams on the Lower Mohawk River, NY. In Mohawk Watershed Symposium 2014. (Download paper here)

[14] Garver, J.I., 2018. Ice Jam flooding on the lower Mohawk River and the 2018 mid-winter ice jam event. In: Cockburn, J.M.H. and Garver, J.I., Proceedings from the 2018 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady NY, 23 March 2018, v. 10, p. 13-18. (Download paper here).

[15] Cockburn, J.M.H., Garver, J.I., Abrupt change in runoff on the north slope of the Catskill Mountains, NY, USA: Above average discharge in the last two decades. J. Hydrology: Reg. Stud. (2014). Download this paper here.

[16] Ice Jam mitigation panel 2020 report to the Reimagine the Canals Task Force. Released January 2020 (Available here).

[17] Garver JI. 2020. Ice Breakers on the Mohawk: A new strategy aimed at mitigating ice jams in Schenectady. Mohawk.Substack.com Link here.