Saving the Stockade from flooding

Approach to flood mitigation in a historic district in upstate NY: 2011-2018

Inundation from Hurricane Irene in 2011 was the catalyst for what has been a decade-long quest for flood mitigation in the historic Stockade district of Schenectady New York. Late in 2018 the first phase of an $8 million FEMA-funded project commenced, and it was aimed at flood mitigation and building resilience into the community. I started investigating ice jams in 1996, and I’ve been following and documenting flooding in the Stockade ever since. The mitigation effort has been complicated, and in some senses difficult to follow because it has evolved slowly and episodically over a decade. But along the way a number of key events have been pivotal in getting us to where we are today. I felt I needed to reconstruct the timeline so that I could better understand how we got here and where we may be headed. In organizing this post, I have tried to follow critical events in a chronological way; the ongoing FEMA-funded project - the last two years - is covered in a separate post.

The dramatic flooding associated with Hurricane Irene and then Tropical Storm Lee in 2011 resulted in the highest water levels in the Stockade District of Schenectady in nearly 100 years. Water at the crest of Irene nearly reached the elevation of the flood with a 1% annual probability, also known as the 100-year flood. While Hurricane Irene had profound impact in upstate New York in 2011, Hurricane Sandy did the same downstate in 2012. Thus in this two-year period, New York grappled with the enormous task of rebuilding. Part of the underlying theme for rebuilding was to build resilient communities that are poised to take on a changing climate. With federal funding, New York embarked on an ambitious plan with New York Rising, a program under Governor Cuomo’s Office of Storm Recovery. The New York Rising plan for Schenectady involved a number of mitigation solutions and was the first time we started to see an integrated plan emerge for that part of the Stockade that sits on the floodplain. In 2017, a single house was lifted and raised above the Base Flood Elevation (BFE), but this effort was complicated and drawn out due to issues with historic preservation. But raising of this house above the BFE was part of a process that involved thinking through how to address flood mitigation in a district with over 300 years of continuous inhabitation and where buyout and demolition is really not an option.

This is a nationally significant effort. In the United States we’ve been seeing an increase in flooding, flood-damaged properties, and concurrent mitigation solutions. There have been a number of important cases where entire towns have been moved to higher ground, and Valmeyer, Illinois, is probably the best example [1]. In this instance the whole town was rebuilt in a field well above the floodplain following the devastating Great Flood of 1993 on the Mississippi River. But the issue of flood mitigation in historic areas is complicated – wholesale relocation is not possible and demolition is off the table. Thus this effort in the Stockade seeks to preserve homes, many of which are several hundred years old, and also to preserve neighborhoods and streetscapes. In short, the plans involve mitigation solutions aimed at preserving our national heritage and thus this case study will be followed closely by other communities in a similar situation.

Historic homes

The historical significance of the Stockade cannot be understated. It was established well before the United States became the United States and before New York was a state. Settled by the Dutch in 1661, the Stockade is one of the oldest occupied neighborhoods in the US. The National Park Service has described the Stockade as "the highest concentration of historic period homes in the country," with over 40 houses older than 200 years [2]. The Stockade was New York's first local historic district [2] when it was recognized by the city council in 1962 [3]. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973 and its boundaries were increased slightly in 1984 [4][5]. The city and an active neighborhood association, the first founded in Schenectady, work to protect its historic character.

The Stockade has homes designed with Dutch Colonial, Georgian, Federal, and Victorian architectural styles [4]. It weathered the French and Indian War, the Revolutionary War, and events since, including major fires in 1690 and 1819 [3]. When George Washington visited and inspected the Stockade in 1795 during the Revolutionary War, the Stockade had already been a village on the Mohawk for over a century [5].

Hazard mitigation

The ongoing efforts build on over a decade of maneuvering and preparation to address the flood problem in the Stockade. The Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 (DMA2000), which amended the Stafford Act that addressed disaster mitigation, tied disaster mitigation to local and state pre-planning, and from this emerged the All Hazard Mitigation Plans (AHMP) at both the State and County levels [6]. With an AHMP in place, local municipalities, such as Schenectady, can apply to FEMA for disaster mitigation funding. Thus the Schenectady County 2006 AHMP that was marshaled forward by Jim Kalohn, then the City Planner, was a critical step in addressing hazards, including flooding. This was an critical first step in getting us to where we are now. DMA2000 requires that plans are updated every five years, the last plan for Schenectady County was released in 2016 [7] and the 2021 update is ongoing.

Irene flooding in the Stockade. The Mayor of Schenectady, Gary McCarthy, being interviewed by WNYT on 29 August 2011 during flooding associated with Hurricane Irene on Washington Street in the Stockade. This flood would initiate a decade-long effort to address flooding in the historic Stockade (Photo: JI Garver).

With a hazard mitigation plan in place, counties are eligible for grant funding for disaster relief and hazard mitigation. In the Schenectady County plan, the highest risk score for all evaluated hazards for the county is flooding, and the risk is highest for the municipalities of Schenectady, Rotterdam, and Glenville – all because they are adjacent to the Mohawk.

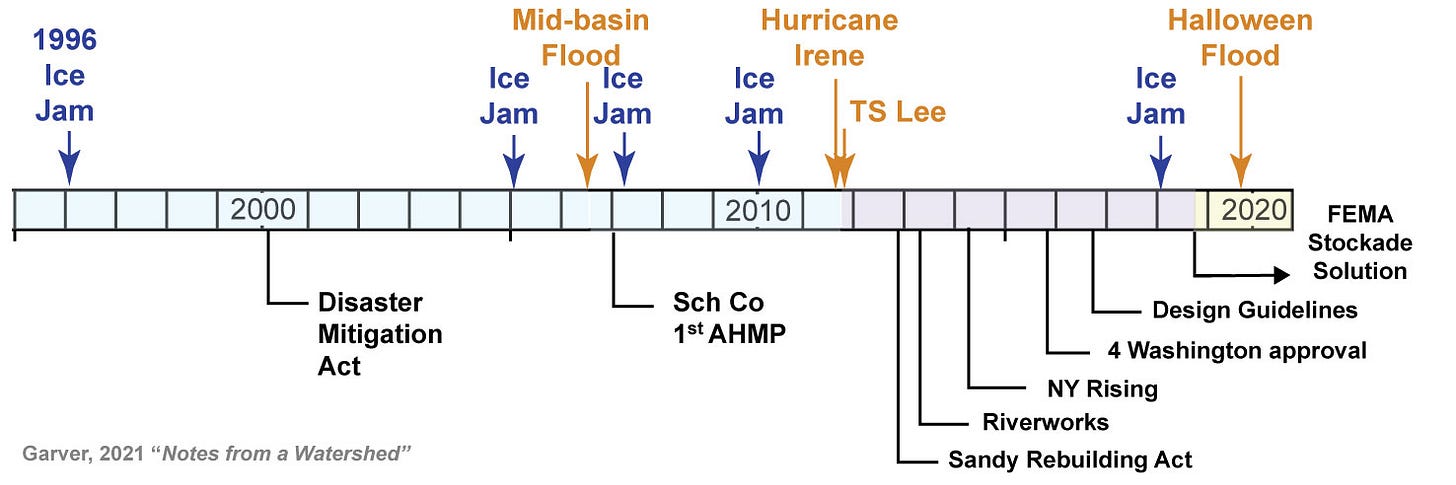

A timeline for flood mitigation in a historic district. The Stockade gets flooded by both ice jam floods (blue) and freewater floods (gold). Major freewater floods in the Mohawk Watershed are shown, and of these only Irene and Lee made a significant impact in the lower Mohawk and the Stockade. Key milestones on the bottom of the timeline are discussed below.

Some have said that this is the first - and last - best chance at getting a significant and effective mitigation project accomplished in the Stockade that will preserve the integrity of this historic district. If successful, the solution will be nationally significant because it can demonstrate how effective strategies can preserve historic areas that are flood-prone. We cannot condemn, buy out, and tear down our heritage, so this project may illuminate the path forward for historic preservation in other architecturally-significant locations in the US. So, with preservation as a guiding principle, how do we solve this problem?

2013 Riverworks

After Hurricane Irene focused a spotlight on flood mitigation, one of the first projects to emerge was Abovewater by Matt Donham and Rebecca Hill from RAFT landscape (NYC). The project examined how communities along the Mohawk River could approach solutions to flooding [8]. This was dramatic and bold. A central idea of Abovewater was integrating the River and river-proximal properties into a long-term forward-thinking plan that fundamentally addresses not only flood mitigation, but also urban planning and green space. Abovewater was released in 2013 and focused on large-scale solutions to urban flooding in a changing climate. The project was funded by the NY State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) and sponsored by The Architectural League of New York [8].

The primary product of the grant was a short video called Riverworks. The video, which can be seen here, took a simple and direct approach to flooding and large-scale community solutions. In part, Riverworks advocated for relocation and retreat from the river’s edge, while simultaneously increasing green space along the river, which would then become a central piece of the urban fabric. Riverworks focused on two communities in the Mohawk Watershed: Herkimer and Schenectady (the Stockade). In a summary, Donham and Hill note that the study “led us to believe that communities need to face the futility of flood repair in certain areas so they can imagine a longer-lasting, more effective solution [to flooding]” [8]. This comment about “the futility of flood repair” has resonated with me because that is where we are now, and it is not working.

The four-and-a-half-minute video follows “Bob,” a typical but hypothetical homeowner in the watershed. In some sense Donham and Hill took a pretty radical view: let’s move all the houses on the flood plain to vacancies elsewhere in the Stockade and completely free the floodplain. Bear in mind that only a faction of the Stockade is on the floodplain, and it has a considerable footprint above the floodplain. A major advantage to this large-scale relocation effort would be a new large river-proximal park that could be a star in the constellation of parks and green space in the City of Schenectady. The downside is that all homes on the floodplain need to be moved and thus established neighborhoods get broken up.

A frame from the “Riverworks” video shows a possible reconfiguration for the Stockade. In this diagram (which I modified with added text) the central idea is to move all homes off the floodplain (blue). These homes get placed elsewhere in the Stockade (red), and the new green space is added to Riverside Park [8].

Donham and Hill maintain that “River Works” are communities that utilize the river to enhance community assets, improve river access, build healthier environments, bolster the economy, and reduce future costs of flooding. This approach is seen as a way to help river-lining communities deal with the growing challenge of flooding related to climate change.

In 2014, Rebecca Hill wrote: “Context-sensitive solutions to flooding can increase the economic strength of neighborhoods while buffering homes and businesses from future damage. Traditional approaches to flooding, such as building a wall or raising buildings, are single-benefit and are neither economically productive nor flexible” [9].

2014 NY Rising

The NY Rising Community Reconstruction (NYRCR) Program was announced in April 2013 by Governor Cuomo as part of the Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery (GOSR) [10]. The $650 m effort allowed communities to plan and rebuild after flooding. A focus was on building resiliency, and that meant that plans needed to include some mitigation measures that would reduce flood damage in future floods.

The NY Rising plan emerged after the devastating flooding in upstate NY from Hurricane Irene and then Tropical Storm Lee in 2011, and subsequent flooding downstate in 2012 largely due to storm surge from Hurricane Sandy. The NY Rising community reconstruction plan for the City of Schenectady and the Town of Rotterdam was a year-long effort; the final report was released in March 2014 [11]. This plan was one of many in the State, and essentially the best proposals were competing across the State for a piece of the $650 m pie.

Sarah Crowell of the NYS Department of State, Office of Planning and Development, coordinated the effort. She has worked for sustainable and resilient development in the State, and in 2015 she wrote: “Through the bottom-up NYRCR planning process, NY Rising Community Reconstruction Plans (NYRCR Plans) were developed to identify projects and initiatives that incorporate and capitalize on local needs, strengths, and challenges to help communities to recover and become more resilient to future flooding.” [12]

Although NY Rising was a NYS program, funding was from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Community Development Block Grant – Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program. NY Rising Communities could request between $3 m and $25 m for eligible projects. One of the important outcomes of this effort was the prioritization of recovery and mitigation projects. So unlike the earlier AHMP, which identified problems, the NY Rising effort was focused on finding solutions. Those projects that did not receive funding did receive attention because they were viewed as a priority. So at this point it was important to get on the list - and the Stockade flood mitigation effort got on the list.

One proposed NY Rising project was entitled “Mitigation Measures to Reduce Flooding in the Historic Stockade and East Front Street Neighborhoods.” This proposed plan included evaluation of three options aimed at reduction of future flood damage in the historic Stockade [11]. The three alternatives for flood mitigation were:

1) Elevate homes in the 100-year floodplain

2) Demolish and elevate to partly preserve Stockade and widen Riverside Park

3) Elevate streets and homes

At the time it was appreciated that this was a complicated plan, so it was suggested that implementation be divided into two phases. The first phase was the evaluation phase, and it was budgeted at $500k to determine the path forward given the complexity related to the historic status of the Stockade. The second phase was the implementation phase, and that was not budgeted because it required selection of one of the alternatives. We will see that this approach parallels what actually happened four years later with the successful proposal to FEMA.

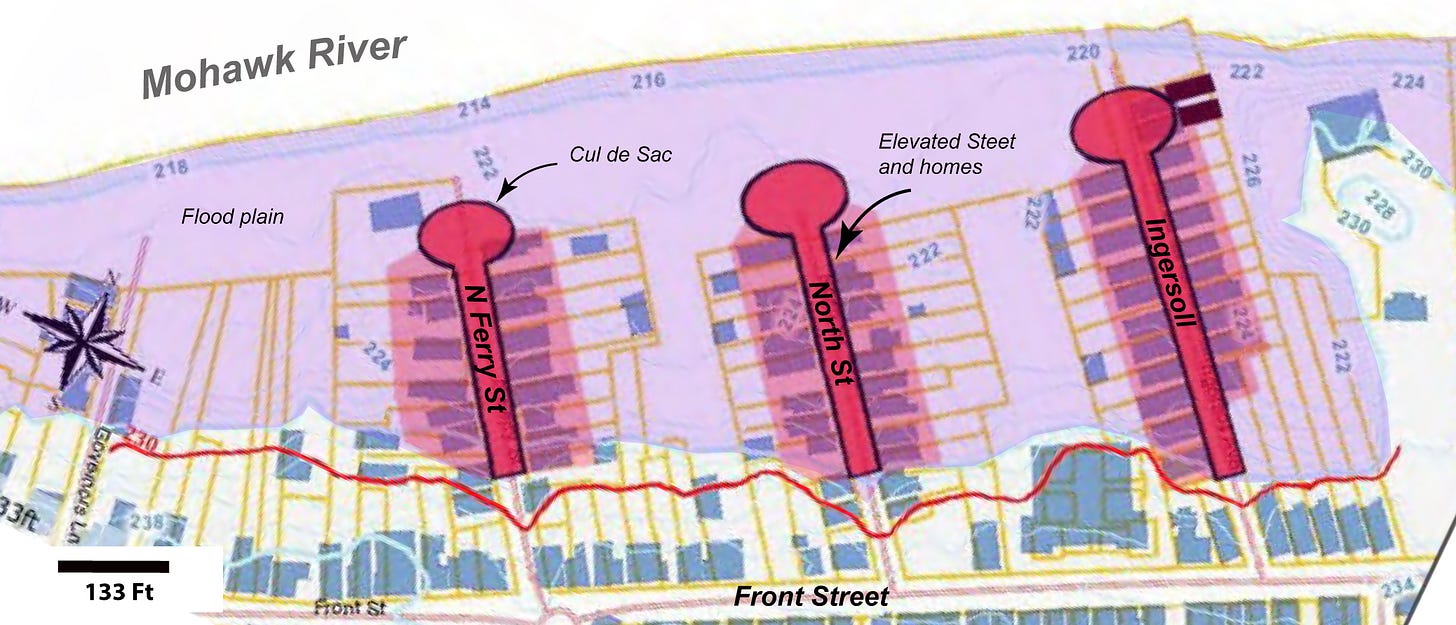

One key to understanding thinking at the time is Alternative 3 [11]. This is the plan to elevate both streets and homes that became known as the “Gilmore Plan” because it was the idea of Frank Gilmore, a Stockade resident and architect at Stracher, Roth, and Gilmore. A schematic of that plan was included in the NY Rising report (11 - see p. 116, but reproduced below). It was clear at the time that the Gilmore Plan was a bold, new, and different approach to addressing chronic flooding in the Stockade: elevate all the homes and many of the streets on the floodplain.

The Gilmore Plan for flood mitigation in the Stockade: elevate homes and streets. This plan advocated by Stockade resident and architect Frank Gilmore appeared in the NY Rising document released in March 2014. Red streets are elevated as are homes and adjacent land (shaded). This was one of the first dramatic plans to address flooding. A major advantage is that the plan preserved the historic integrity and neighborhood fabric (figure modified from p. 16 of NY Rising) [11].

A number of other mitigation items made the first cut in the NY Rising plan as either Proposed Projects or Featured Projects, and the Stockade mitigation “study” was one of the Proposed Projects. Several flood mitigation projects did not make the first cut, and these ended up as “Additional Resiliency recommendations,” and one of them was a study of the role that the Vischer Ferry Dam plays in flooding, especially in the Stockade. Inclusion of this project was advocated by Jim Duggan, a longtime resident of the Stockade who was on the NY Rising committee. The document states that “The purpose of this study is to evaluate the effect of the dam on flooding, and investigate a possible engineered adaption of the [Vischer Ferry Dam]” (see 11 - p. 156). The proposed budget for investigating the VFD: $30k, an insignificant amount in the big picture. It was not funded.

Preserving Historic Integrity. As explained, the Stockade is New York State’s first historic district. The oldest structure in the Stockade is the Yates House (not on the floodplain), built in c. 1725 [11] and reputedly the oldest home in the City. The mix of homes in the Stockade has evolved over three centuries, and thus it is a unique neighborhood in the US and worth preserving. “Rooted in Dutch and English precedents, the Stockade District is a collage of architectural styles from pre-Revolutionary structures to Georgian, Federal, Greek and Gothic Revival through late-Victorian and early twentieth century residences.” [13]

Framers of the NY Rising plan appreciated the historic nature of the Stockade, and they understood the complexity that this designation presents for flood mitigation. They note that the best plan for flood mitigation will “...consider the preservation of the integrity of the entire neighborhood. Because of the historic significance, it is possible that State and Federal funds could become available that are in excess of the direct value of the sum of the individual values of each home” [11 - p.113]. This is an important point: preserving one of the oldest and longest-occupied neighborhoods in the US will be expensive if it is to be done right. The framers continue, and obliquely explore who will bear the costs:

“This is a complex plan. It involves the relocation of utilities, coordination of effort of all homeowners, approvals by numerous agencies... historic preservation review... and costs that would exceed the value of the sum of the homes. Since the homes would be preserved and increased in value, homeowners could be expected to assist in defraying some costs” [11 p 115]. This last point is important yet complicated. Most dramatic mitigation schemes really require 100% participation, and thus there is the potential for a tug-of-war between homeowners and those doing the reconstruction.

2015-17 First home elevated above the BFE

Consider what is involved to move and elevate a 200-year-old brick house. The David Heatsey house on Washington Street, which is on the 100-yr floodplain, provides a critical case study for this exercise. This house has late-Federal architecture and was flooded to the first floor in Hurricane Irene [13]. With a grant from the Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery (GOSR), the homeowner, Meredith Anker, approached the Schenectady Historic District Commission about the move, which would result in moving the house back off the street 15-20 ft and up 6.5 feet [14].

That increase in elevation would put the house to the Design Flood Elevation (DFE), which in NY State is two feet above the Base Flood Elevation (BFE). In common parlance the BFE is the 100-year floodplain, but technically it is the elevation of the water in a flood that has a 1% annual probability. Note that if the house were simply elevated in place there is no room for the required stairs to get to the first floor (you can see in its original position it is very close to the sidewalk). Thus in many plans for elevating houses, the house needs to be moved back from the street to accommodate stairs or else the street must be elevated as well. Recall that this latter approach – elevating both the street and the houses - was central to the Gilmore Plan.

The Anker home in the Stockade – the only historical house on the floodplain that has been raised to an elevation above the Base Flood Elevation (BFE). The BFE is the elevation of water in a flood that has a 1% annual probability (aka “100 year floodplain”). In NY State the Design Flood Elevation (DFE) is the BFE + 2 ft. Photo to left (before elevation) from the City Flood mitigation guidelines [13], and to the right (after elevation) in the Spring of 2019 (photo: JI Garver).

In June 2015 Meredith Anker was interviewed by Pete DeMola of the Schenectady Gazette about the potential of elevating her home above the 100-year floodplain (or BFE). In this interview she revealed the stress of living on the floodplain, especially after Irene: “For a long time I thought I would sell my house because I can’t handle the strain of whenever it rains. It’s just too much. It’s too aggravating. It’s too scary. But I don’t know that I could ever sell my house because the flood insurance is astronomical. And every time the water rises, and it rises every year, you never know if it’s going to come through. It used to be we just worried about ice jams, but recently with the hurricanes coming up the coast, I just can’t handle the anxiety” [15]. Undoubtedly there are others in the Stockade who have similar feelings.

Getting permission to move and elevate the house was an ordeal, partly due to following strict guidelines for the Stockade aimed at maintaining historical integrity. She petitioned the Schenectady Historic District Commission in June 2015, and the Commission finally agreed to allow her to move and elevate in November 2015 [16]. In an interview with Haley Viccaro of the Daily Gazette she had clearly been frustrated by the delay: “I found them not to be supportive or cooperative but obstructionist-minded. They didn’t want it from the beginning and kept bringing up negative things. To have to fight so hard to save my house is very frustrating.” [16]. Imagine if every homeowner on the flood plain had to go through this.

The Commission voted 6-1 to allow her to raise her home. The lone vote cast against the move was by Marilyn Sassi who at the time felt that steps would be taken to prevent flooding on the River. She was quoted at the time: “I feel that from everything I’ve investigated that a lot of improvements have been made with the dams in our area and the locks....We had about four days warning with Hurricane Irene. There was such horrible destruction, I cannot believe it could ever be allowed again” [16]. We hear this misconception about river flooding regularly, but the stark truth is that flooding of the River is common and in this setting it cannot be controlled with hard structures like dams. Flooding in the Stockade will happen again.

The move of 4 Washington Street was made in September 2017. A local Stockade resident, Holly Van Voast, watched the house move and was quoted as saying “To me, this is cooler than putting someone on the moon... They just picked up this little brick house. I’ve never seen anything like it” [17]. The cost of the move has not been made public, but the Daily Gazette reported that the total cost of the move was ~$300k [18], and it was funded in large part by a grant from the NY Rising Community Reconstruction program, part of the Governor's Office of Storm Recovery (GOSR) [14]. If we consult Zillow, an online evaluator of home prices, we discover that the cost to elevate that historic home is greater than the assessed price of the home, but there is no doubt that the value of the home increased significantly because it is no longer on the flood plain so the insurance burden is much lower.

While 4 Washington Street was being elevated and rehabilitated, a steering committee presented specific guidelines for homeowners thinking about flood-proofing their homes in the Stockade [19]. This effort resulted in the Stockade Historic District “Flood Mitigation Design Guidelines” [13], which was the next critical piece of the puzzle.

2017 Flood Mitigation Design Guidelines

A Request for Proposals or RFP is a common way to outline the specific criteria for funding and the bounds and limits of specific projects. The City put out an RFP in January 2017 for bids to develop guidelines for flood mitigation projects. The effort was funded by New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation (OPRHP) [20]. The timeline was tight: proposals were due in early February, and the selection and award occurred by early March, and then delivery of the guidelines was required by August 2017. In the RFP, the City noted “The intent of the guidelines is to protect the historic character of the properties and the district as a whole when houses are elevated or otherwise modified to protect against flood loss.” [21]

In August 2017 the Flood Mitigation Design Guidelines were completed. The plan was led by Mesick Cohen Wilson Baker Architects who specialize in the historic preservation of culturally significant buildings. The final product is an amazing document. It details the requirements for mitigation projects in incredible detail...down to the specific house. It is carefully crafted to preserve streetscapes, historic integrity, landscaping, and neighborhood feel.

When elevating homes there is considerable work to do with the front porch, stairs, and other elements related to a change in the front of the house. We can see this in the example at 4 Washington Street. An example of the detail in the RFP is the requirement for new building elements, where the Guidelines document states: “All new building elements at the main street elevation such as windows, stairs, landings, foundations, and porticos shall be designed to be contextual with the design style and materials of the original building and traditional building design principles while not conveying a false sense of historical development, in accordance with the Secretary of the Interior Standards.” [13, p. 32].

Specifics of landscaping were also required. An excerpt, here simplified: “Landscaping should complement the architectural elements of the residence. Species selection should reflect historic character of the Stockade. Plants, such as arborvitae, that are in contrast to the character of the Stockade Historic District, shall not be used. Invasive species such as barberry and burning bush are prohibited. Some good examples of foundation shrubs include: hydrangea, lilac, viburnum, fothergilla, roses, yew, holly, daphne, deutzia, red osier dogwood, and boxwood” [13]. What we learn from this interesting document is that the RPF is detailed, thorough, and squarely focused on historic preservation.

2018 FEMA funding for an integrated flood mitigation plan

In 2016, the City applied for FEMA funding for pre-disaster mitigation for homes on the floodplain in the Stockade. This $8.6 m plan was a two-pronged approach: first study options, and then implement a solution – a similar approach to what was in the NY Rising plan. In September 2017 there were pressing national needs associated with damage in the southern US from Hurricanes Irma and Harvey, and thus FEMA delayed funding and decisions for long-term mitigation projects [18]. Given FEMA funding and preservation guidelines, an RFP from the City was released in June 2018 with proposals due in July 2018. At the time the City had hired Margaret Irwin, Principal of River Street Planning, for all project management services related to the proposal. The RFP called for all work for Phase 1 to be completed in one year (fall 2018 to fall 2019).

In the fall of 2018 The City of Schenectady announced that it had been awarded a FEMA grant through the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program through the NY Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Services (DHSES) to determine the best path forward with flood mitigation in the Stockade. Thus the final step, which is ongoing, is the best opportunity to address flooding in the Stockade.

The FEMA funded effort since 2018 is the subject of a following post. It is important to bear in mind at this point that the ongoing mitigation effort has a history with an interesting evolutionary timeline that has undoubtedly resulted in a stronger plan.

This and other Notes from a Watershed are available at: https://mohawk.substack.com/

Further Reading

[01] Elam, S.E., 17 July 2019. A flood forced this town to move. It could be a model for others hit by the Climate Crisis. CNN. Link HERE.

[02] Wikipedia entry for the Stockade - Here.

[03] The Schenectady Stockade in Spring. Life as I see it photography. Blog post here.

[04] The Stockade Association. Website here.

[05] Schenectady Stockade, Schenectady NY – Revolutionary Day. Webpage here.

[06] Schenectady County All Hazards Mitigation Plane – 2006. (plan no longer on internet)

[07] Schenectady County All Hazards Mitigation Plane – 2016. Plan here.

[08] Protecting the past from a watery future. Project web page here.

[09] Hill, R. The Resilient neighborhood: Flood mitigation as an Economic engine. In Cockburn, J.M.H. and Garver, J.I., Proceedings of the 2014 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March 21, 2014. p. 23.

[10] Governor’s Office of Storm recovery (GOSR) - Website here.

[11] NY Rising – Schenectady Rotterdam, 2014.

[12] Crowell, SS. 2015. Accomplishments and status of NY Rising. In: Cockburn, J.M.H. and Garver, J.I., Proceedings of the 2015 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March, 20, 2015, p.14.

[13] Stockade Historic District Flood mitigation design Guidelines, 2017. City of Schenectady Planning document. (aka RFP 2017)

[14] Nelson, P. 16 November 2015. Panel Oks plan to elevate Schenectady home above flood zone; Months after request, board allows shift away from Mohawk River. Times Union.

[15] Demola, P. June 6 2015. Owners want to elevate Stockade home. Meredith Anker wants to raise her home 6½ ft to better protect it from the Mohawk River. Daily Gazette.

[16] Viccaro, H., November 16 2015. Homeowner allowed to raise, move Stockade house. Approval could set precedent. Daily Gazette.

[17] Samuels, B. 13 September 2017. After months of prep, crews move Stockade house on wheels; 'This is cooler than putting someone on the moon,' one resident said. Daily Gazette.

[18] Williams, S. 19 Sept 2017. Stockade FEMA mitigation funding on hold. Comes in wake of hurricanes Harvey, Irma. Daily Gazette.

[19] Samuels, B. 30 August 2017. Committee to submit Stockade flood-mitigation guidelines Consultants: Flood mitigation efforts could bring quality-of-life improvements. Daily Gazette. Article here.

[21] Stockade historic district flood mitigation design guidelines, City of Schenectady NY Department of Development. January 2017. Guidelines here.