Stop the invasion: barriers needed between the Mohawk and the Great Lakes

Recent capture of the Round goby in the Hudson River highlights the need to address invasive species in the Erie Canal Corridor

In July 2021 the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation (NYS DEC) announced that the invasive Round goby, a small omnivorous fish from eastern Europe, had been captured in the Hudson River downriver from the confluence of the Mohawk River [1]. These fish are the latest in a parade of invasive species to use the Erie Canal Corridor (ECC) to jump from the watershed divide between these two different and distinct ecosystems. Since this announcement I have written several opinion pieces (in Schenectady Daily Gazette here and in the Buffalo News here) that note that the need for a barrier in the ECC is critical and long overdue [10,11].

The particular fish is forgettable, but its invasion is remarkable. River life will adapt, but it will be forever changed, with likely impacts on striped bass, sturgeon, and other iconic river species. The invasion was predicted, and even inevitable, because we haven’t taken one of the most important actions to promote the health of not only the Hudson, but also the Great Lakes: build invasive species barriers in the Erie Canal corridor.

For several years now progress of the Round goby has been monitored by netting and eDNA surveillance, and there was a hope that this invader would be restricted to the upper Mohawk watershed. I recently wrote about the progress and range expansion of the Round goby here [2]. The USGS and the NYSDEC have been monitoring the advance of these invasive fish for years, and it is well known that they entered the Mohawk from the western end of the Erie Canal. The simplest explanation of this recent finding that the Round goby are now in the Hudson River is that they successfully navigated the length of the Mohawk and continued into the Hudson. In fact the eDNA monitoring along with capture has uniquely demonstrated the progression and path of this invasion out of the Great Lakes along the ECC and into the Hudson. Thus these scientific data demonstrate that the ECC was used by this invasive species to cross the watershed divide.

In the discovery announcement (here) the NYS DEC noted that “These fish are voracious feeders and compete with native species for food and spawning habitat. Their diet includes small invertebrates, mussels, and the eggs of native species and popular sportfish such as smallmouth bass and walleye. They also can be a nuisance to anglers.” [1] Thus there is concern that this development may harm the sport fishery in New York. The detrimental effects of these fish have just started.

While range expansion of the Round goby was monitored by the DEC and USGS, there was nothing that could be done to stop, slow, or otherwise affect the progress of the invasion front. All we can do is monitor and watch as these invaders arrive and damage the ecosystem. We need a new approach to stopping invasive species, especially in the ECC, which is a raceway for dispersal and range expansion. Since the ECC was established, very little has been done to control or regulate invasive species and fish passage in the Mohawk corridor that links different ecosystems on either side of the watershed divide.

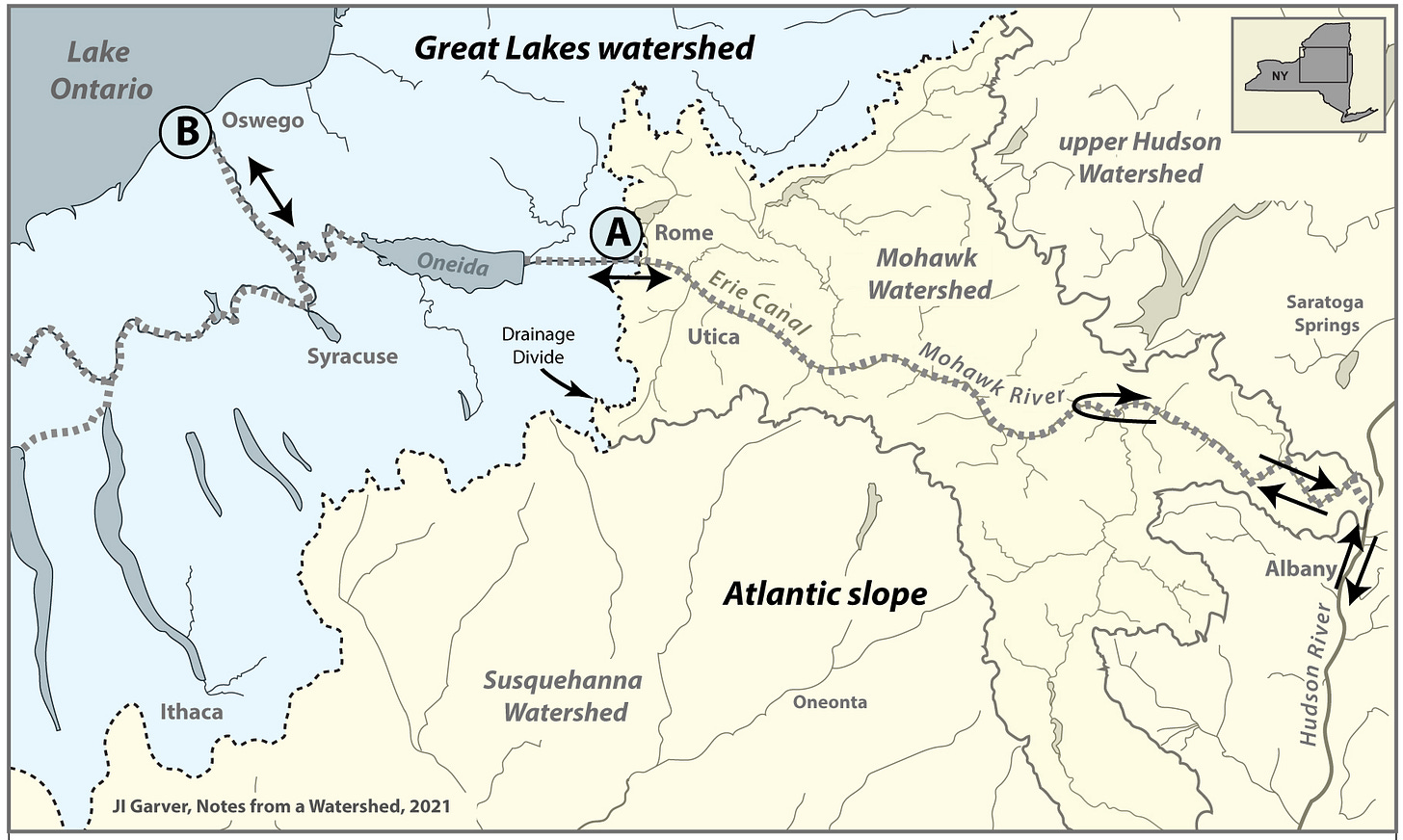

The Mohawk Watershed, part of the Hudson-Mohawk drainage on the Atlantic slope, occupies a natural topographic low exploited for construction of the Erie Canal. For nearly 200 years fish and aquatic invasive species have used this connection for range expansion. Much of the detrimental activity, especially in the last century, involves connection between the watershed and the Great Lakes (at “A”). Planning for invasive species also includes interrupting connections directly into the Great Lakes (“B”) at Oswego and also near Buffalo (not shown). Some fish, like River herring, enter the Mohawk through the Waterford flight, and then return to the Hudson (see arrows), but some of them have continued across the divide.

Fish. Fish in the Mohawk watershed are native, introduced, or invasive. The current assemblage of fish has been profoundly affected by the establishment of the Erie Canal, which for nearly 200 years allowed a direct connection between the Mohawk-Hudson and the Great Lakes watersheds [3]. Construction of the ECC altered the nature of the watershed framework and allowed for two connections that were otherwise barriers: one at the confluence of the Mohawk and the Hudson and one at the drainage divide (A in diagram) in the uppermost part of the watershed.

Thus, from the beginning, canal connections have facilitated range expansion of non-migratory fish and other invasive species. This has been especially true in the last ~110 years, when the Mohawk River was employed directly for canal operation; since this latest phase of the ECC, completed in 1916-18, aquatic connections across the divide have been simpler and more direct. As an additional complication, the establishment of the St Lawrence Seaway in 1959 has opened the Great Lakes to a series of ecological challenges, especially those related to invasive species introduced from contaminated ballast water in trans-Atlantic ships [4].

Fish have used the ECC corridor to cross the drainage divide near Rome to move either east or west. Norm McBride of NYS DEC Fisheries division noted that fish that have moved west include Sea lamprey, Alewife, and White perch [3]. Fish that have moved eastward include Smallmouth bass, Gizzard shad, and Freshwater drum, which were first documented in 1990 at Lock 7 and are now everywhere in the River [3]. Given the recent success of the Round goby, and the threat of Asian carp (Bighead and the Silver carps - discussed in a recent post here), perhaps it is time to rethink this connection and focus on environmental sustainability and ecosystem health.

Reimagining the future of the Erie Canal Corridor (ECC). A goal of the 2020 Reimagine the Canals effort [5] is centered on bringing the Erie Canal into the 21st century, and this means transitioning from a transportation artery to a recreational and historic corridor. Thus it is worth thinking about possible changes that can be made to limit or stop the spread of aquatic invasive species (AIS) while simultaneously enhancing and protecting the fishery. The Reimagine the Canals task force appointed by Governor Cuomo looked into methods to address aquatic invasive species along the ECC (read the task force report here).

The corridor has been referred to as the “Invasive Superhighway” because the canal is a direct connection between the Mohawk-Hudson and Great Lakes watersheds. Many, but not all, invasive species started in the Great Lakes and migrated through the canal to the Hudson watershed. Many detrimental and problematic aquatic organisms have been accidentally introduced into the Great Lakes, with Zebra mussels and Round goby among them. But the list is long and invasion occurs from west to east (e.g., Zebra mussel, Freshwater drum, Round goby) and from east to west (i.e. White perch, Sea lamprey, Alewife).

Early in the Reimagine the Canal effort, participating stakeholders along the length of the canal indicated that controlling invasive species should be a top priority [5]. The Task Force commissioned a study to evaluate options for addressing a broad range of Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) along the ECC corridor [6]. In the report, the consulting firm advocated an “All AIS species” approach, which means mitigation solutions for both “unassisted dispersers” (such as White perch, Asian carp, Sea lamprey, etc.), and others that cling or attach to boats that are essentially “hitchhikers” or those that are assisted by transport by boats (such as Eurasian watermilfoil, Hydrilla, but also those that lay eggs on vegetation, such as the Round goby). AIS experts interviewed for the AIS study agreed on several principles or overarching ideas that need to guide mitigation approaches.

Two guiding principles emerge from this analysis: 1) The NYS Canal system poses a risk of spread of invasive species to the majority of inland water bodies in NYS; and 2) the Great Lakes watershed and the Mohawk-Hudson watershed need to be separated [6]. In the final report, the consultants recommended the Watershed Divide alternative, which aims to prevent spread of AIS from the Great Lakes.

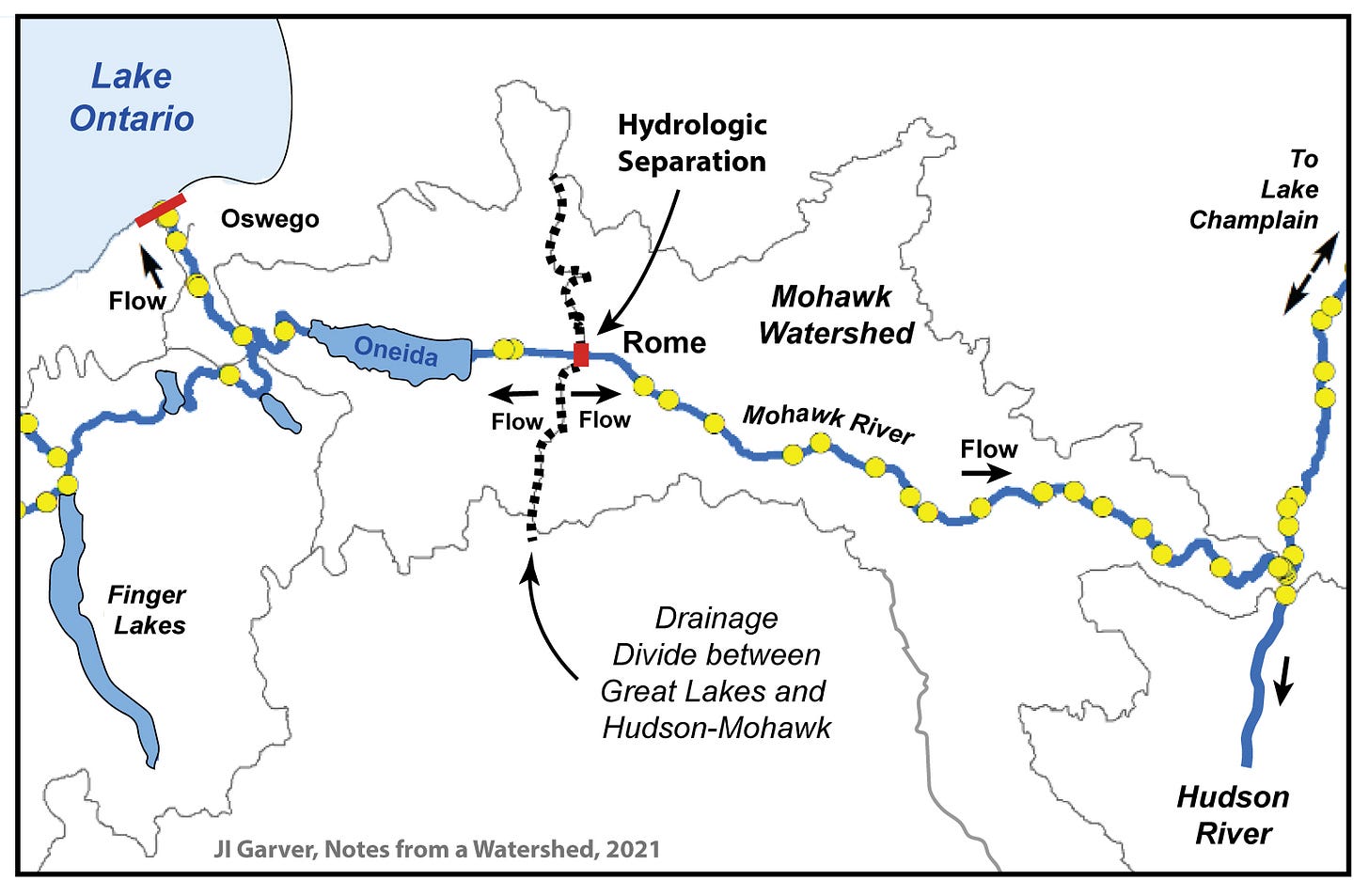

One primary component of this preferred alternative is hydrologic separation at Rome to protect the Mohawk Watershed and the Hudson from the invasive species entering from the west. Hydrologic separation means installing a barrier in the water that effectively separates water on either side of the barrier. There are many options for a barrier that range from deterrents in the water (electricity, sound, light) to filling in a short section of the canal. In any scenario, a primary goal would have to be maintaining boat traffic.

The location of the possible interventions in the ECC aimed at stopping invasive species, here showing the eastern two of four total options. Figure modified from [5]. Yellow dots are locks, and red lines are possible locations of barriers.

Great Carrying Place. There is considerable history in the Mohawk corridor that predates the Erie Canal, and one of the most notable is the Great Carrying Place near Rome, New York. A key theme in this history is the protection and fortification at the drainage divide, because this area has been a strategic pathway for centuries. In the early to mid 1700’s the Great Carrying Place, was critical for trade, especially for the Six Nations fur trade by natives of the Iroquois confederacy [7]. In 1762 Fort Stanwix was built at the Oneida Carry, the 4-8 mile portage between the Mohawk and Wood Creek that eventually leads to Lake Ontario (the length of the carry varied depending on water levels). The National Park Service notes that “the Oneida Carrying Place was one of the most critical points on the route to the Great Lakes…” [8]

The construction of Fort Stanwix by the British was partly to protect the Mohawk valley from invasion from the west where the French had a number of successes in the Great Lakes and the St Lawrence corridor. Today the reconstructed Fort Stanwix is a US National Monument that highlights this rich history. As noted by the National Park Service: “For centuries, the Oneida Carrying Place, a six-mile portage connecting the Mohawk River and Wood Creek, served as a vital link for those traveling by water from the ocean to the Great Lakes. When Europeans arrived, nations fought for control of the carry, the homelands of the Six Nations Confederacy, and the rich resources of North America.” [8]

Given the current urgency of addressing aquatic invasive species on the Erie Canal Corridor, and the importance of watershed separation, perhaps this may be an opportunity to highlight the pre-canal history of this critical area. Hydrologic separation and the infrastructure to transfer boats across the barrier at Rome could be a vehicle to celebrate that history. Hydrologic separation may involve a carry that takes boats a short distance up and over the divide.

With innovative engineering, this facility could be an attraction that could highlight not only the importance of the aquatic separation but also the historical significance of this historic area. If done correctly the new “Great Carry” or the “Stanwix Carry” would add almost no additional time to a typical boat journey on this canal, and it may well take the same amount of time as a typical lockage.

Pathway forward. For nearly two centuries the ECC has been an invasive pathway between the Mohawk-Hudson and the Great Lakes; the result has been an ecological disaster. We need to invest in barriers to invasive species, especially at the drainage divide, to protect and restore ecosystem balance. With innovative engineering that dovetails with the unique historical setting, the hydrologic separation may well be a local attraction that would result in minor disruption to boat traffic. The new “Great Carry” could highlight the important pre-canal history of this area, which involves both Native Americans and early colonists.

This effort matters to all of us who are stakeholders in the basin, especially those who fish and boat in the watershed. We will all benefit if we are successful in stemming the tide of invasive species. At this point, we need to embrace a plan that relies on modern engineering solutions that can take on the invasive challenge while simultaneously maintaining the historic integrity of the Erie Canal and boat passage.

In a recent online conversation entitled “Science for the Future of the Hudson River” aquatic ecologist Stuart Findlay of the Cary Institute noted that “...the cheapest and most effective thing we can do is keep out the next set of invasive species. The ones we are really worried about now are these invasive Asian carp….[which are] extremely damaging ecologically... Right now they have a wide open back door into the Hudson, and that’s the Erie Canal.” [10].

Let’s close that door.

This and other Notes from a Watershed are available at: https://mohawk.substack.com/

Further reading

[01] NYS DEC announcement Here on the capture of four Round Goby in the Hudson River in 2021.

[02] Garver, JI, 2019. Invasion of the Round goby: Benthic predator threatens sport fishery but eats zebra mussels. Notes from a Watershed. (Note this post was fist written in Dec 2019, but then updated in 2021.) (link here)

[03] McBride, N. 2009 – Lower Mohawk River Fisheries. In Cockburn, J.M.H. and Garver, J.I., (Eds), Proceedings from the 2009 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady NY, 27 March 2009. p. 51-54. Link here.

[04] Egan, D., 2017. The death and life of the Great Lakes. WW Norton & Company.

[05] Reimagine the Canals Task Force Report. January 2020. Available here.

[06] R2 Resource Consultants Inc., 2019. Erie Canal Aquatic Invasive Deterrent Study. 296 pages. Report to the Reimagine the Canals task force. Available here.

[07] National Park Service, “The Oneida Carry and Its Early Fortifications: 1755-1757 Link here.

[08] National Park Service. Fort Stanwix: History, Historical furnishing, and historic structure reports. Construction and Military History 1758 to 1777 1. The Oneida Carrying Place and its early forts. (link here)

[09] Findlay, S. 2021. Science for the future of the Hudson River. (Interview) https://www.caryinstitute.org/news-insights/lecture-video/science-future-hudson-river

[10] Garver, J.I., 5 August 2021. Containing invasive species critical to Erie Canal. Opinion. Buffalo News, Buffalo NY.

[11] Garver, J.I., 19 August 2021. Address Erie Canal invasive species now. Opinion. Daily Gazette, Schenectady, NY.

What a great readable mix of science, ecological awareness, Indigenous history, eco-tourism, engineering, and imaginative problem-solving. You have my vote!