Asian Carp have not made it to the Erie Canal, but we are at a critical juncture where decisions that we make now may well affect our ability to keep these and other invasive species out of the Canal and Mohawk watershed in the future. Asian Carp are well-established in the Mississippi watershed, and complex and costly efforts are ongoing to keep them out of the Great Lakes. A large fraction of that effort and money is focused on barriers in the Chicago Area Waterway system (CAWS) that connects the headwaters of the Illinois River to Lake Michigan.

There are two primary routes for invasive species to jump watersheds in and out of the Great Lakes. One is CAWS, which connects the Great Lakes to the Mississippi watershed, and one is the Erie Canal Corridor (ECC), which connects the Great Lakes to the Mohawk-Hudson River Basin. Both connections were engineered in the nineteenth century to facilitate boat traffic across watershed boundaries. Both have become a focal point for the role they play in allowing invasive species to move from one watershed to another. Mitigation efforts are intense at CAWS, while they are not at the ECC. This situation needs to change.

In his book Overrun, Dan Reeves writes that the “North American collaborative approach to managing the Asian carp crisis has become the largest cooperative ecological endeavor undertaken on the continent” [3].

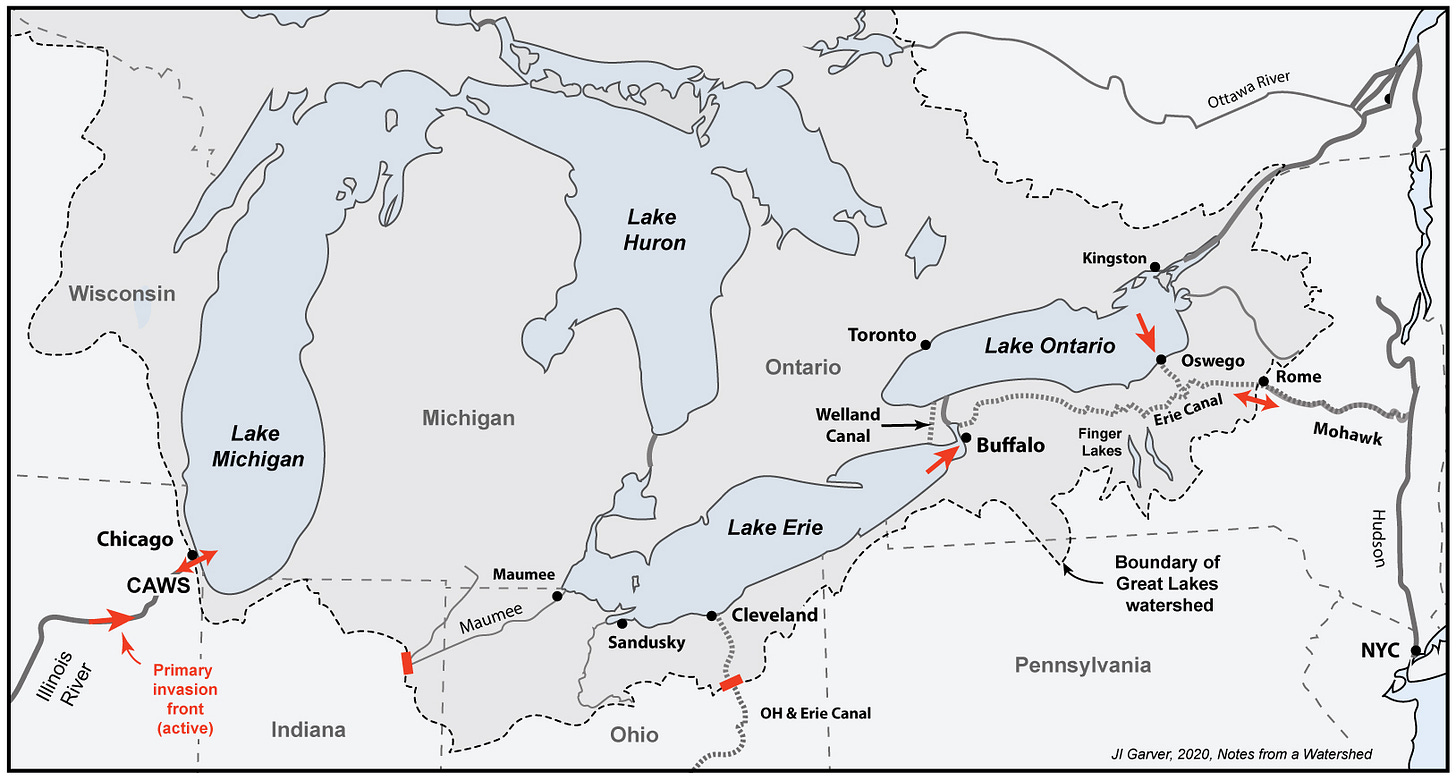

Map showing the Great Lakes watershed with pathways into and out of the basin. The invasion front of Asian Carp is primarily in the Chicago Area Waterway System (CAWS), but projects have addressed ephemeral connections to the Maumee and the Ohio and Erie Canal in Ohio. From the perspective of the Erie Canal Corridor (ECC), the entry points of concern are at Buffalo and Oswego. The last line of defense for the Mohawk is at Rome NY.

If this is a war on Asian Carp, the current battle is focused on the primary invasion front at CAWS and on possible pathways in Ohio. However, future battle plans are now being considered for the eastern theater – the fight aimed at keeping invasive species out of the Erie Canal so they do not eventually end up in the Finger Lakes and Mohawk-Hudson watershed. Many people are worried about this possibility, and some would suggest that the clock is ticking and we need to start planning for this eventuality now to prevent an ecological catastrophe. Invasive species have already been successful in using the Erie Canal to invade the Mohawk Hudson River Basin (MHRB) from the Great Lakes, and I recently wrote about two successful invaders: Zebra mussels and the Round Goby [1,2] – both transited from the GLB to the MHRB. But the list of invaders is long and from a ecological perspective one could argue that the ECC has been a disaster.

This note is not about the history of introduction nor the profound ecological impacts of the four species of Asian carp that threaten our waterways and native fishery. For that I recommend the highly readable, thoroughly researched, and engaging book entitled “Overrun: Dispatches from the Asian Carp Crisis” by Andrew Reeves (see that book here) [3]. Instead I am interested in thinking about how the current war on Asian Carp might play out in the eastern front over the next decade. If these fish breach the primary line of defense in CAWS and make it into the Great Lakes, including Lake Erie, it will be an ecological catastrophe. But what if they continue and the invasion front enters the Erie Canal in NY? Do we have any chance of stopping these fish? What can we do now to pre-position? There are many Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) of concern in NYS, and most steps we take now to address Asian Carp will also slow or stop other species of concern, so this is really about stopping invasive progress and isolating watersheds.

There are four species of introduced carp from Asia: Bighead, Silver, Black, and Grass carps. The two species of high concern are the Bighead Carp (Hypophthalmichthys nobilis) and the Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix), which are collectively referred to as “Bigheaded carps” (BHC) in the literature [i.e. 4].

USACE and CAWS

Asian Carp have invaded much of the Mississippi watershed, including the Ohio River. A large breeding population is present in the Illinois River, and this is connected to Lake Michigan by the Chicago Area Waterway System (CAWS). CAWS includes the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (CSSC) and several other waterways, and part of the original usage was to facilitate barges and boats for commerce [5]. It is now a complex system used for commercial traffic, recreational boating, and storm water conveyance. Without continued intervention, this is the primary pathway that Asian Carp will take into the Great Lakes. Thus it is the focal point of considerable mitigation efforts.

Up to this point the main line of defense has been operation of the Electric Dispersal Barrier System (EDBS) in the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal (CSSC) by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) [6], but the effectiveness of the EDBS has been questioned because apparently fish can get through [32, 33]. Some have advocated full hydrologic separation. Jerry Rasmussen and colleagues wrote a 2011 paper entitled “Dividing the waters: The case for hydrologic separation of the North American Great Lakes and Mississippi River Basins.” In that article they are clear in their message: “Hydrologic separation is the only option which closes the aquatic connection between the two basins and does not require continuous operation and maintenance of various technologies that have some risk of failure.” [33].

A 2014 report released by the USACE had six alternatives to stop the invasion front and keep Asian Carp out of the Great Lakes. The plans included structural and non-structural changes to prevent spread of Aquatic Nuisance Species (ANS) from leaving the Mississippi watershed and entering the Great Lakes [8]. In August 2017, the “Tentatively Selected Plan (TSP)” was the Technology Alternative – Acoustic Fish Deterrent with Electric Barrier. In late 2018 the decision was made at the USACE to fully embrace the Technology Control method (i.e., Alternative 4 in the 2014 report) [9]. This decision meant that alternatives that embraced hydrologic separation were, essentially, rejected. The favored option includes installation of an acoustic fish deterrent, water jets, a newly engineered channel, and an electric barrier at the Brandon Road Lock and Dam [34]. For passage of boats it includes a flushing lock and new boat launches [10]. Based on a composite of expert opinions, it is estimated that even after mitigation there is still a 10-17% probability that Asian Carp will invade the Great Lakes [10]. The plan will cost ~$830 m, and will cost $12.3 m to operate annually [11]. In July 2020, the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee passed legislation that authorized construction of the project [12].

There are other possible avenues that Asian Carp can take to get into the Great Lakes. The USACE appears not only to have identified them [14], but also to have begun actively working to close them [13, 3]. The most recent closure, completed in 2020, involved a multistep process to isolate waters on either side of the drainage divide on the Ohio-Erie canal that connects Lake Erie with the Ohio River, where Asian Carp are now present. The Ohio & Erie Canal Aquatic Nuisance Species Barrier Project involved the installation of screens, fences, and improved bank height near Barberton OH to reduce the possibility of invasion into Lake Erie during floods [13,14].

Robert Hirschfeld, water policy specialist at the Prairie Rivers Network, who has been involved with efforts on the now-infested Illinois River, has an an ominous warning in the film Against the Current. “For far too long the threat of carp was not taken seriously, and by the time it really was on the radar of decision makers, carp were everywhere” [30].

Habitat in the Great Lakes and Lake Erie

Obviously a major concern is that Asian Carp get into the Great Lakes and then continue to spread from there. We are not at that point, but how close are we? How do we monitor their progress? There appears to be widespread agreement that the best and most effective surveillance technique is environmental DNA (eDNA) from surface waters to detect the presence of specific species. While considerable work has gone into eDNA research in the CAWS and Lake Michigan, what about Lake Erie?

The Maumee, Sandusky, and Grand Rivers, which drain in to western Lake Erie, are most likely to support spawning of Asian Carp because their ecosystems are suitable - these rivers have the right temperature and flow conditions [15]. Marc Gaden of the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, said: "There's nothing in the Great Lakes right now that leads us to believe that Asian carp won't find good feeding and spawning grounds. The lakes will be welcoming to these fish if they get in" [16].

Perhaps the most significant eDNA surveillance finds have been from western Lake Erie where small populations of Grass carp appear to have been established, but evidence also indicates that Bighead and Silver carp have been present in these waters. In 2013, Christopher Jerde, then from the Environmental Change Initiative at the University of Notre Dame, published results with colleagues from eDNA surveillance using samples taken in 2011 and 2012 [17]. Samples with positive eDNA from BHC were taken from Sandusky and Maumee Bay where six of the samples were positive. It is possible the these fish were introduced to Lake Erie in the early 1990’s based on otolith dating, and that they were not likely migrants from CAWS [17]. Nonetheless, these results are concerning.

In 2014, Chris Wilson at the Aquatic Research and Monitoring Section of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources published results with colleagues from 948 eDNA analyses from the entire length of the Canadian side of Lake Erie, including western Lake Erie, with no indication of Bighead, Silver, or Grass carp [18]. At the same time (2014), Andrew Tucker at the Nature Conservancy and colleagues were sampling in Buffalo Harbor and elsewhere in the western part of the ECC [19]. I contacted Andrew and he told me that results from the study were not published, but they had not detected Bighead or Silver carp in the surveys, including from Buffalo Harbor.

PRISM in NYS

Detection and intervention of AIS in NYS is not new, and there is a network in place to address threats, and identify and address problems. Part of that effort is the Partnership for Regional Invasive Species Management, or PRISM [20]. The PRISM partnership is with NYS DEC, and the objective is to monitor and track invasive species in the eight PRISM districts in NYS. Three PRISM districts are the gatekeepers to the MHRB (although may have a different perspective). The SLELO (Saint Lawrence and Eastern Lake Ontario) includes the western Adirondacks, but also monitors the Oswego River and Canal that is a direct link from Lake Ontario. The Western New York PRISM monitors a large region that includes the gateway between Lake Erie and the western part of the Erie Canal [20]. There is a Capital Mohawk PRISM, but one can imagine that if they detect Asian Carp (BHC), it’s too late.

The Coordinator for the Western NY PRISM is Andrea Locke at Buffalo State University. For the Western NY PRISM, Bighead carp and its allies are a “Tier One species of concern.” This means it is “not-present/ approaching region,” and tier one is the highest level of early detection efforts. I wrote Andrea and asked her about BHC monitoring efforts. She noted that they list Bighead and Silver carp species as Tier 1 in part to support federal partners, and they “recognize how important it is that they are kept from entering the system. We do also include them in our education and outreach efforts and help disseminate information as needed or requested.”

She explained that the status of Grass carp is different, partly because they are used to control aquatic vegetation, including Hydrilla (an invasive aquatic plant). An issue that she points out is that “triploid sterility isn’t as absolute as promoted.” This means that diploid fish, capable of reproduction, are inadvertently being released in NY State (as triploid, which are unable to reproduce). Thus Grass carp are a more difficult species to control because attempts to identify an invasion front are complicated by legally-released individuals.

The Coordinator of the SLELO PRISM is Robert Williams with The Nature Conservancy. He told me that the SLELO PRISM is actively using eDNA qPCR techniques to monitor Tier 1 species. The SLELO PRISM has several published reports with results of eDNA studies that targeted Round Goby, Northern Snakehead, and four Asian carp species [21,22]. In 2016-17 they analyzed 180 water samples from four rivers on either side of the first “impassible barrier.” Round Goby was widely detected, Northern Snakehead was detected in Oswego, and Grass carp was detected in Oswego. Bighead and Silver carp were not detected anywhere in their study area.

Capital Region PRISM is hosted by the Cornell Cooperative Extension of Saratoga County and coordinated by Kristopher Williams. He told me by email that they were not actively monitoring for carps in the Mohawk, but he was aware of the problem and funding possibilities to support monitoring efforts.

ReImagine the Canals and Invasive species in the ECC

It is a good time to consider how to mitigate the ECC invasive pathway because efforts are underway to reimagine what the Canal will look like in the future. In 2019 the Reimagine the Canals task force (herein Task Force) looked into the future of the Erie Canal and one major focus area was invasive species [G3]. The Erie Canal has been referred to as the “Invasive Superhighway” because the canal is a direct connection between the Hudson and Great Lakes watersheds, and since its establishment a number of species have used the canal to spread. Most, but not all, invasive species started in the Great Lakes and migrated through the canal to the Hudson watershed [G3]. Many detrimental and problematic aquatic organisms have been accidently introduced into the Great Lakes, with zebra mussels and Round Goby among them. The invasion of the Round Goby is ongoing and surveillance indicates it successfully crossed the watershed divide and invaded the Mohawk watershed between 2014 and 2019; it is presumably working its way downstream to the Hudson.

Stakeholders along the Canal are well aware that invasive species are a problem. Early in the Reimagine the Canal effort, stakeholders were asked about key concerns in Community Engagement sessions. These sessions, hosted by the Rockefeller Institute, were held at different locations along the Erie Canal Corridor as part of the Reimagine effort. In both the central and western sections stakeholders clearly indicated that controlling invasive species was a top priority. The report on these stakeholder meetings noted: “Participants were universally concerned with the spread of invasive species and the effect that these species have on both ecosystems and water recreation...” [24].

The Task Force commissioned several studies from outside consultants, and these included detailed investigations into ice jamming, flooding, fishing, irrigation, wetlands, reconnecting tributaries, and invasive species. The invasive species study, released in January 2020, is titled “Erie Canal Aquatic Invasive Deterrent Study” and it was conducted by R2 Resource Consultants in Redmond, Washington [25]. While the report was aimed at a broad range of Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS), it specifically considers mitigation and prevention of Asian Carp, one of the priority species of concern.

The report advocated an “All AIS species” approach, which means that mitigation solutions for both “unassisted dispersers” (such as Asian Carp), and others that cling or attach to boats that are essentially “hitchhikers.” So it is possible that they would have come up with other strategies if they concentrated only on invasive fish, but the all AIS approach is the right approach. Experts in AIS management who were involved with discussions for the study agreed on a few guiding principles: 1) the Canal poses a risk of spread of AIS; 2) both real and avoided costs need to be considered in mitigation efforts; 3) the Great Lakes and the Mohawk-Hudson watershed need to be kept separate; and 4) efforts need to focus on the most destructive species. This last point is where Aquatic Invasive species (AIS) narrows to Aquatic Nuisance Species (ANS) [25].

In the evaluation, they advanced six different mitigation strategies, some related to stopping only hitchhikers (pressure washing, steam washing, etc.). Other strategies were focused on stopping unassisted dispersers, which we will herein refer to as fish (although there are others in this group). These fish-stoppers include Screens, Bio-acoustic fish fences (BAFF), and Hydrologic Separation [25].

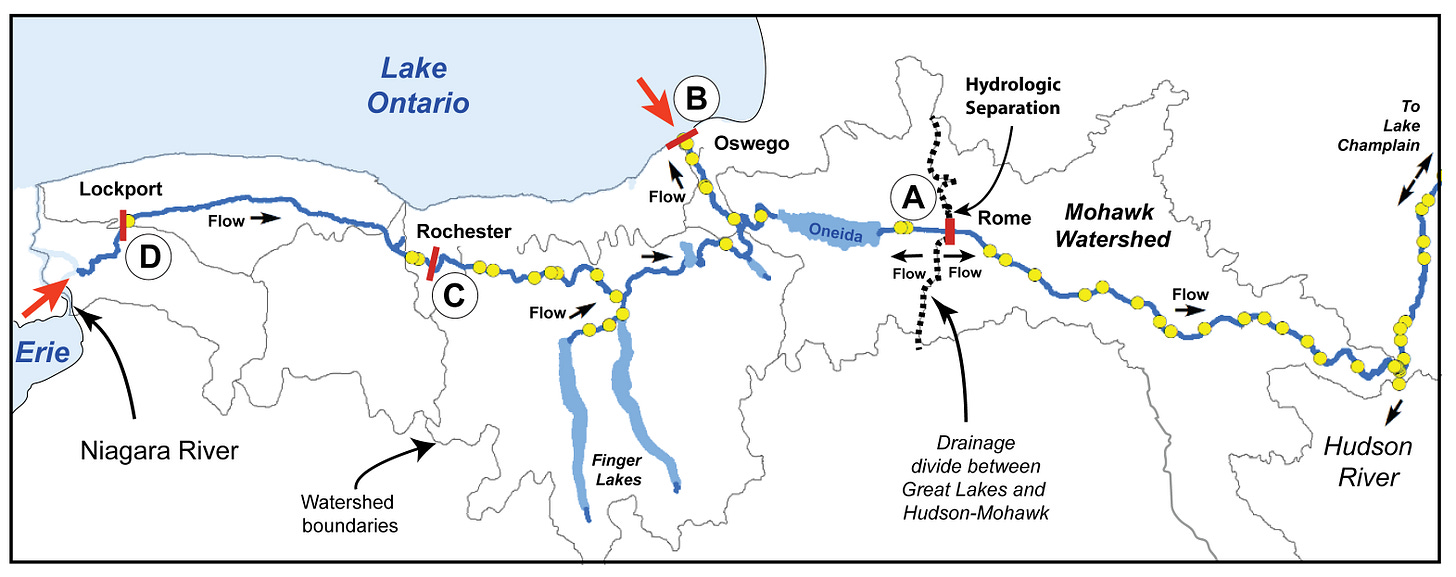

The consultants recommended their Alternative 2 – Watershed Divide, which aims to prevent spread of AIS from the Great Lakes to the Finger Lakes, Oneida Lake and the Hudson watershed. The suggestion was driven by consideration of cost and of effectiveness. The approach would result in barriers or hydrologic separation at four key locations, each with a strategy. They include: A) Hydrologic Separation at Rome to protect the Mohawk Watershed and the Hudson from the canal to the west; B) Boat Lift at Oswego to prevent transit from Lake Ontario to the canal; C) Hydrologic Separation at Rochester to protect the Finger Lakes and Oneida from the western canal; and D) Bioacoustic Fish Fence at Lockport to deter Asian Carp that leave Lake Erie through the Niagara River. Bear in mind that there are two primary routes from the Great Lakes into the ECC: from the Niagara River into the western Canal (D); and from Lake Ontario into the Oswego (B).

The location of the four possible interventions in the ECC aimed at stopping invasive species. Figure modified from [25].

Two of these four strategies target the front doors of invasion from the Great Lakes. The boat lift at Oswego would result in a hydrologic separation between the Erie Canal and Lake Ontario. The BAFF in Lockport would be a biologic gate between the western Erie Canal and Lake Erie. The consultants asked experts to rank how the different strategies satisfied project criteria, and not surprisingly hydrologic separation (filling in part of the Canal) scored the highest (100 on a normalized scale of 100). Bioacoustic fences scored 70 on the same scale, presumably partly because the technology is relatively new: it is currently being tested at the Barkley Dam near Grand Rivers, Kentucky [26]. The estimated cost of the watershed divide alternative (Alt 2) would involve initial capital costs between $8.5 m and $18.2 m and annual operating costs of ~$1.4 m.

In the final analysis, the Task Force recommended that the options for invasive control be studied further, and this suggestion emerged from the Governor’s plan in January 2020. The announced plan focused on repurposing the Canal to develop and grow regional tourism, reduce flooding in Canal communities (especially in the Mohawk), improve irrigation and expanding fishing opportunities in the western ECC, and restore wetlands in the central ECC [27]. Invasive species control was not on the list of action items.

Closing the canal?

It is incorrectly assumed that hydrologic separation at the watershed divide means stopping boat traffic. If we embrace interesting and exciting engineering solutions, a boat lift may be the highlight of crossing the watershed divide. The Elblag Canal in Poland has five sections where boats are lifted and moved overland [31]. The system uses a trolley lift and then track and rail to move the boats between canal sections. It can handle boats up to 24 m long and the longest transport is ~250 m. In the US, the Morris Canal in New Jersey included such a system nearly 200 years ago where inclined planes were used to move coal-bearing boats.

Today, the Big Chute Marine Railway on the Trent-Severn waterway in Ontario is an inclined plane that lifts boats from the Severn River into Georgian Bay [35]. This boat lift functions, in part, to prevent migration of invasive species. It was originally built as a temporary solution in 1914, but in 1976-78 this cradle-on-track system was enlarged to stop the invasion of the Sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) [36]. It can carry boats up to 30.5 m, and it not only moves boats but it has become a tourist attraction. A boater recently wrote on Trip Advisor: “What an experience going through the Big Chute Marine Railroad. We brought our boat through two months ago and what an experience. The men manning the Big Chute Railroad are well organized and had us through in short order. Earlier than expected really.” This system is fast, efficient, and interesting, and it has stopped invasion of lamprey.

The old Big Chute Marine Railway on the Trent-Severn waterway, Ontario. The new upgraded lift can be seen at the Parks Canada website, here (Photo: Creative commons, credit here).

A well-crafted hoist and transfer system could be a highlight of the ECC and an interesting tourist attraction. Let’s think outside the box and solve this 19th-century problem with 21st-century engineering solutions.

Carpe Diem

The idea of closing part of the canal by hydrologic separation is not popular. While the Task Force evaluated different reports and options, the R2 Aquatic Invasive Deterrent study was leaked to the press and its findings were evaluated without context. In August 2019, the Buffalo News (and others) published pieces critical of the process [i.e., 28]. However, later that fall (October 2019), the Buffalo News published an editorial that was thoughtful and deliberate. In this editorial, they stated:

“The question is how much that history [of the Erie Canal] should influence thinking about how to shield the [Great] lakes from environmental degradation... What is undeniably important today is the need to protect Lake Erie and its sisters from the destructive influence of invasive species....If cutting the flow of water through the canal plays a critical role in preventing that [environmental degradation], then Buffalo and the rest of upstate should be open to the possibility” [29].

For nearly 200 years the Erie Canal has served as an invasive pathway between the Mohawk-Hudson and the Great Lakes. One could argue that this experiment has been an ecological disaster. It’s time the Canal enters the 21st century with the rest of us. We need invasive species barriers to protect the delicate balance in the ecosystems that have evolved in that time. Taking on invasive species is going to be a complex and involved process. One of the first things we need to do is understand and appreciate how ecosystems suffer when new species are established.

Preparing now for Asian Carp should only be part of a more integrated plan that addresses the threat of all aquatic invasive species across watershed boundaries in New York State. The success of zebra mussels and ongoing invasion of the Round Goby and the imminent threat of the Northern Snakehead remind us how easily species migrate across the watershed divide. Thus this is not just about Asian Carp, it’s about protecting our watersheds, protecting our ecosystems, and supporting the valuable sport fishery in the state of New York.

George Jackman is Senior Habitat Restoration Manager at Riverkeeper and thus well-qualified to assess the impact that Asian Carp would have on the MHRB. I contacted him to get his sense of the damage if Asian Carp get into the watershed. He told me that “if Asian carp were to enter the Hudson River, the dynamic equilibrium of the ecosystem would be upended, causing a cataclysmic environmental impact. Currently, all of the most iconic, native fishes of the Hudson River Estuary are in decline and most are already suffering from depleted populations. The introduction of the Asian carp… would be catastrophic, as they would potentially collapse the ecosystem forming an alternative stable state that would be nearly impossible to overturn.”

The clock is ticking and lack of any barriers on the Erie Canal has already resulted in major ecological transformations in the ECC and the Mohawk-Hudson watershed. We need a plan, and we need to embrace new engineering solutions, and it is probably best if this plan emerges from stakeholders in New York. But, we need to get started on this effort now to avoid this potential future cataclysmic impact on the ecosystem.

This and other Notes from a Watershed are available at: https://mohawk.substack.com/

Further reading

[01] Garver, JI, 2019. Invasion of the Zebra Mussel: They took the canal expressway across NY State in 1991-92. Link here.

[02] Garver, JI, 2019. Invasion of the Round Goby: Benthic predator threatens sport fishery but eats zebra mussels. Link here.

[03] Reeves, A., 2019. Overrun: Dispatches from the Asian carp crisis. Toronto, Ontario: ECW Press.

[04] Alsip, P.J., Zhang, H., Rowe, M.D., Rutherford, E., Mason, D.M., Riseng, C. and Su, Z., 2020. Modeling the interactive effects of nutrient loads, meteorology, and invasive mussels on suitable habitat for Bighead and Silver Carp in Lake Michigan. Biological Invasions, 22(9), pp. 2763-2785.

[05] EPA - Chicago Area Waterway System / Chicago River. Available here.

[08] Great Lakes and Mississippi River Interbasin Study. Available here.

[09] Flesher, John, AP. Cost of keeping Asian carp from Great Lakes nearly triples. Available here.

[10] Executive summary of final report (The Great Lakes and Mississippi River Interbasin Study – Brandon Road Final Integrated Feasibility Study and Environmental Impact Statement – Will County, Illinois). Available here.

[11] Eaton, Sabrina. 2019. Army Corps estimates Asian carp containment measures will cost more than $830 million, new report says (cleveland.com) May 25 2019. Link here.

[12] Cass, Andrew, 21 July 2020. Project aimed at keeping Asian carp out of Great Lakes passes U.S. House committee. News Herald. Link here.

[13] USACE, Oct 2020. Ohio & Erie Canal project complete, Project Team to host webinar. Available here.

[14] USACE Great Lakes Mississippi River Interbasin Study (2014). Available here.

[15] Kocovsky, P.M., Chapman, D.C., McKenna, J.E., 2012. Thermal and hydrologic suitability of Lake Erie and its major tributaries for spawning of Asian carps. J. Great Lakes Res. 38, 159–166. Available here.

[16] Daniel Cusick, 8 July 2020. Warming Could Lower One Barrier to Invasive Fish Reaching Great Lakes- Mussels in the lakes, themselves invasive species, may not be able to outcompete Asian carp for food, as previously thought. In: Scientific American. Available here.

[17] Jerde, C.L., Chadderton, W.L., Mahon, A.R., Renshaw, M.A., Corush, J., Budny, M.L., Mysorekar, S. and Lodge, D.M., 2013. Detection of Asian carp DNA as part of a Great Lakes basin-wide surveillance program. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 70(4), pp.522-526. Available here.

[18] Wilson, C., Wright, E., Bronnenhuber, J., MacDonald, F., Belore, M. and Locke, B., 2014. Tracking ghosts: combined electrofishing and environmental DNA surveillance efforts for Asian carps in Ontario waters of Lake Erie. Management of Biological Invasions, 5(3), p.225. Available here.

[19] Pignataro, T.J., 2014. Environmental DNA pinpointing Buffalo Harbor invasive species. Buffalo News. Link here.

[20] NYS DEC PRISM in NY State. Link here.

[21] Williams, R.K., and Bengtsson, Z.A, and Fedrizzi, N., 2017. USEPA-Great Lakes Restoration Initiative Project Final Technical Report. Available here.

[22] Williams, R.K., and Bengtsson, Z.A, 2020. Using environmental DNA (eDNA) and underwater video as early detection tools for invasive fish in four Eastern Lake Ontario tributaries. SLELO Whitepaper. Available here.

[23] Reimagine the Canals Task Force Report. January 2020. Available here.

[24] Fox, S., Schultz, L, and Turner, R., 2019. Reimagine the Canals Community engagement report. Sept 2019, Rockefeller Institute of Government. 23 p. Available here.

[25] R2 Resource Consultants Inc., 2019. Erie Canal Aquatic Invasive Deterrent Study. 296 pages. Available here.

[26] Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee, Feb 2020. 2020 Asian Carp Action Plan. Available here.

[27] Cuomo Press release, 6 January 2020. Governor Cuomo Announces 29th Proposal of the 2020 State of the State: $300 Million Plan to Reimagine the Iconic Erie Canal. Available here.

[28] Prohaska, T.J., 12 August 2019. Stakeholders wary of Cuomo’s plans to ‘reimagine’ state’s canal system. Buffalo News.

[29] Editorial News Board, Buffalo News, 20 October 2019. Editorial: With the Erie Canal, it’s history vs. the environment.

[30] GLN editor. October 2020. “Carp Advance: Real and potential impacts of invasive fish throughout the Midwest,” which features the film “Against the current” and an interview with Drew YoungeDyke who made the documentary. Available here.

[31] The Elblag Canal in Poland with its unique boat-lift-and-transfer can be seen and read about Here and Here and this Daily Mail article Here.

[32] Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee, Feb 2020. 2020 Asian Carp Action Plan. Available here.

[33] Rasmussen, J.L., Regier, H.A., Sparks, R.E. and Taylor, W.W., 2011. Dividing the waters: The case for hydrologic separation of the North American Great Lakes and Mississippi River Basins. Journal of Great Lakes Research, 37(3), pp.588-592.

[34] Final USACE report and Brandon Road project. Available here.

[35] Parks Canada - Trent-Severn Waterway National Historic Site (web site here).

[36] Marsden, J.E. and Siefkes, M.J., 2019. Control of invasive sea lamprey in the Great Lakes, Lake Champlain, and Finger Lakes of New York. In Lampreys: biology, conservation and control (pp. 411-479). Springer, Dordrecht.