Sale of the Stony Creek Reservoir

Liquidation of this water asset will force reliance on the Mohawk River for the Town of Colonie

In the Capital District of NY State, the Latham Water District (LWD) is poised to sell the Stony Creek Reservoir (SCR), which has been part of its raw water supply since 1953. This sale may be short-sighted because the District will lose a key source of water that is isolated and protected. Removal of the SCR from the raw water portfolio means the LWD will always need to rely on the Mohawk River for its raw water needs. During typical operations, this is not a problem. However, if - or when - there is an emergency or catastrophe on the Mohawk, the District would be at the mercy of adjacent communities for their water. Sale of the SCR - a unique and dedicated source of municipal raw water - may be ill-advised because river water has the potential to be a problematic water source.

Currently the Latham Water District (LWD) can obtain raw water from three different sources: the Mohawk River; the Mohawk View well field; and the Stony Creek Reservoir. The Colonie Dam that forms the SCR was completed in 1953, and the reservoir was used as a source of water up to about 2004 when it was sidelined in favor of the more direct supply of water from the Mohawk River. Since that time, however, NYS State has adopted new dam safety regulations that put greater responsibility for safety on dam owners.

The LWD includes 82,000 people in the Town of Colonie, and typically the population of the LWD consumes about 10 million gallons a day (MGD). In the late summer that demand may be as high as 20 MGD. Thus the supply of raw water needs to support this range of usage (8).

Map showing the Stony Creek Reservoir and Colonie Dam in relation to the Mohawk View Water Treatment Plant, the central hub of raw water for the Latham Water District. Historically, water is drawn from the Stony Creek Reservoir, and then transported by pipe across the river and along River Road to the treatment plant (base map: Google terrain).

A reliable source of municipal water is critical to a functioning society. Many consumers of municipal water take that water for granted and may not fully understand the complexity of the process that takes water from a source and eventually delivers it to the tap.

In municipalities in the Mohawk Watershed, raw water is drawn from three primary sources: rivers, reservoirs, or groundwater. The Latham water district currently has all three. Raw water is then filtered, purified, and chlorinated, and the “finished” water is then distributed and consumed in the community. Regardless of raw water source, chlorination is required to control bacteria and it is added before distribution. In the lower part of the Mohawk watershed, Colonie and Cohoes rely on raw water from the Mohawk.

Raw water for the LWD is processed and purified at the Mohawk View Water Treatment Plant (MVWTP) on the south bank of the Mohawk River. It is at this site where the three water sources converge and treatment of the raw water occurs. Today, raw water is derived primarily from the Mohawk River and is commonly blended with lesser quantities of well water from the five onsite wells (Mohawk View Well Complex). The wells alone do not provide a sufficient quantity for the LWD. The SCR is now reserved as an emergency raw water source but the Town reports that this emergency source has not been used since 2004 (2,8). Abandonment of the SCR was due to rising levels of total organic carbon (TOC), but water in the reservoir has not been tested since 2004 (8).

Reservoir sale and public meeting. The Town of Colonie had a public information meeting on 20 April 2021 where Superintendent John Frazer Jr. presented the current situation of the Latham Water District, including details of the SCR. In that meeting, he noted that the recent renovation of the MVWTP allows for maximum pumping from the Mohawk at 30 MGD. He also noted that the average use by the water district is 10 MGD and maximum use in 2020 of 23.2 MGD. In 2005 the LWD successfully petitioned NYSDEC to draw 31.5 MGD from the Mohawk River.

Because the SCR has never been used as a primary water source, the LWD considers it to be obsolete, and hence the Town is poised to liquidate it (the RFP for bids is here). The Town will entertain a minimum bid of $5.1 m. Sale of the reservoir, dam, and surrounding land would save money for the LWD because there are significant costs associated with maintenance, inspections, and insurance. The sale is opposed by the local advocacy group Save Colonie (15), in part because they note that the sale has lacked transparency.

Three primary issues stood out at the April 2021 meeting. The first is that the LWD now has an interconnect agreement with the Albany Water Board, which means they can obtain finished water in an emergency. The second is that a cited reason to sell the SCR is that the dam that holds up the reservoir - the Colonie Dam - is expensive and a liability. The third is that the sale would mean the LWD would have to rely on the Mohawk River for its raw water needs, and in the event of an emergency the raw water from the Mohawk would be turned off and the interconnect from Albany would be turned on. Let’s take a look at these three issues.

1) Interconnected municipal water. It is typical for adjacent municipalities to connect distribution systems to ensure a continuous supply of finished water in case of emergency or maintenance. An “interconnect” allows connection and sharing of finished water between districts, but this is not a free service: districts enter into agreements that have financial obligations if water is delivered. Recent interconnects between the LWD and Albany have allowed for purchase and use of water from the Albany Water Board in case of emergency or shutdown of the Latham treatment plant on the Mohawk. These interconnects are perfect for short-term disruptions, but some municipalities use them for continuous purchase agreements (for example Niskayuna buys finished water from Schenectady, and Ballston and Charlton buy water from Glenville).

The interconnect agreement between the LWD and the Albany Water Board is a 10-year contract. The physical connection (interconnection) was a $3.2 m project that involved a connection at Albany-Shaker Road and one on New Karner Road (2). In an emergency these interconnects can supply about 10.4 MGD, at a cost. That agreement is exactly what water districts need - across the Capital District - to ensure a continuous supply of finished water for everyone in the district. Based on an April 2021 estimate, the cost of water from Albany would be $5,727 for a day, $43,000 for a week, and $235,000 for a month for 13.2 mgd (8). Thus a months-long crisis would be expensive.

2) Dam safety. The Colonie Dam, which is a NYS Class C (high hazard) dam, is the barrier that created the SCR from a pre-existing natural drainage. Ownership of this high-hazard dam may be a major reason the Town is interested in selling the property. The Town estimates that the annual cost of the reservoir is $224,000 per year (14). A major issue is the liability and insurance costs for the Colonie Dam.

The dam is an earthen embankment with a concrete core wall built and put into use between 1952 and 1953 (8). Classification of a dam in NY State is an indication of the consequences of dam failure rather than the current status or condition of the dam: Class A dams are low hazard, Class B dams are intermediate hazard, and Class C are high hazard. Classification includes an estimate of loss of life and property damage in the event of failure.

Ownership of a high hazard dam (NYS Class C) in New York comes with tremendous responsibilities, both practical and legal. If the Town of Colonie does sell the Stony Creek Reservoir, the Colonie Dam comes with it. Class C dams have the strictest regulations in the State. NY State Dam Safety regulations require annual safety inspections, engineering assessments, maintenance plans, and an Emergency Action Plan or EAP (11). One requirement of the annual safety inspections is an evaluation of the outlet works (reservoir drain) - this was added in the 2009 regulations (12). The required low-level outlet on Class C dams, which requires annual testing, allows for drainage of the water behind a dam in case of an emergency or crisis. There have been issues with the Colonie Dam in the recent past. In the April 2021 informational meeting, John Frazer, supervisor of the LWD, noted that the 2002 failure of the spillway cost nearly $1 m to repair (8). NYS regulations require a low-level outlet for Class C dams, so the idea of “capping the outlet pipes” at the time of sale is not an option if those pipes are the only way to draw down the reservoir.

Dams do fail, and that’s why the State has strict regulations. The 2005 failure of the Hadlock dam - an earthen dam near Fort Ann NY - was an expensive, costly, and damaging event. The replacement cost of the dam was $4.3 m, and the legal settlement with the town was $3.8 m (9). The final settlement with property owners was finally reached in 2017 for an undisclosed amount (10). Perhaps the Colonie Dam is a candidate for removal, which would allow for restoration of the Stony Creek drainage to its original state before the dam was built.

3) Impairment of Mohawk River water. If the Colonie Dam and SCR are sold, the Mohawk River will be the primary future source of raw water for the LWD because the well field alone does not have the capacity to meet water needs for the district. What happens if for some reason the river water in the Mohawk becomes unusable? I teach a class in natural disasters, and one of the things I've learned is the need to expect the unexpected. There are a number of possible threats to water quality in the Mohawk River, and they can be considered as problems that are legacy, chronic, or catastrophic.

Legacy problems are primarily related to our industrial past, but also due to poor planning or less stringent regulations. I recently wrote about radionuclides in the river sediment that were discharged from Knolls Atomic Power Laboratories (KAPL - see map), just upstream from the Vischer Ferry dam (link here - see 19). Research by geologists at RPI show that radionuclides in river sediment get stirred up and remobilized during flood events (including Sr-90 and Cs-137, but also isotopes of Pu - see 19). Poorly cited landfills along the Mohawk River may also be a source of long-term and ongoing contamination of the river. Riverkeeper showed that leachate from the Colonie landfill (just down stream - see map) had elevated per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and there is concern that these compounds may get into water supplies (20, or go here).

Chronic problems may include unintentional releases of sewage from leaky pipes, salt from roads, or permitted industrial discharges. Catastrophic problems are more complicated, but they include potential derailment of trains with hazardous material or an industrial accident that includes a release of chemicals into the River. It may be useful to walk through a few scenarios to better understand the magnitude of potential threats.

In recent history, unexpected things have happened to the Mohawk that have compromised the supply of Mohawk water to Colonie. In the early 1990s, untreated glycol used to deice planes at the Albany International Airport flowed down Shaker Creek to the Mohawk, where it eventually contaminated the raw water supply for Colonie. For a time Colonie stopped drawing from the Mohawk and relied only on raw water from the wells and the SCR (3). This problem was remediated, but only after implementation of a costly and involved system for the collection and processing of glycol at the Airport.

A subtle issue here is that the water intake from the Mohawk is in the middle of the Crescent pool. The Crescent pool is an impoundment on the River that sits between the Crescent Dam (downstream) and the Vischer Ferry Dam (upstream - see map). This geography becomes important during low-flow conditions because the pool can be nearly static, a condition that typically occurs in the summer. The Crescent Dam is fixed in place and permanent, so in the unlikely event of a spill, there is no easy way to “open the gates” and flush water through the system to recharge the pool with uncontaminated water from upstream.

Sewage: chronic and catastrophic. A major ongoing challenge for water quality in the Mohawk is sewage, either from mishaps or from the day-to-day leakage of old sanitary sewer pipes that need to be replaced. Some of the sewage issues are related to catastrophic events or system failures. For example, on 1 May 2021 a pump failure in Amsterdam (up river) resulted in an estimated spill of 1.1 millions gallons of raw sewage being dumped directly into the Mohawk (4).

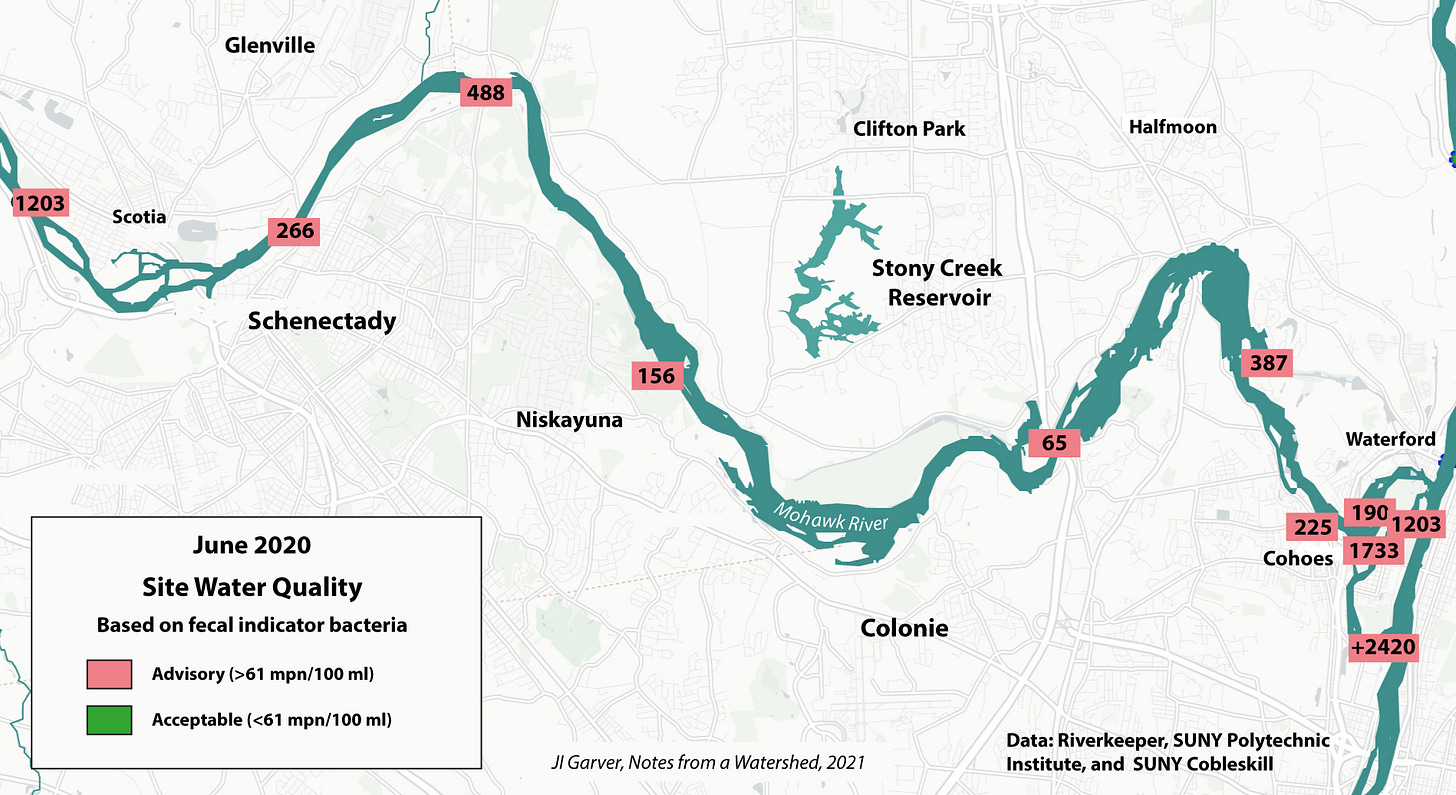

Perhaps even more worrisome are chronic issues related to a leaky and impaired infrastructure, which includes sanitary sewer lines (i.e., 6). Since 2015 Riverkeeper and academic partners at SUNY Cobleskill and SUNY Polytechnic have been testing river water samples for Enterococcus, a fecal indicator bacteria (FIB) commonly related to sewage (see data and reports here). They test 35 sites along the river about six times a year, generally from May to October. If we look at the data from a year ago (2020; see map) we see a grim snapshot of poor water quality on the lower Mohawk River (5). Recall that last summer was unusually hot and dry with low rainfall, and these conditions may have exacerbated this particular event.

Map of the lower Mohawk River showing the results from water testing of fecal indicator bacteria (FIB) done by researchers at Riverkeeper, SUNY Cobleskill, and SUNY Polytechnic (Utica) in June 2020. In this sampling round, every single sample on the lower Mohawk failed to meet the EPA criteria for water quality. This testing has been conducted since 2015, and the June 2020 round was one of the poorest reports we’ve seen on this part of the River.

The poor FIB numbers in the early summer of 2020 are almost certainly related to sewage from leaky infrastructure, combined with low flow on the Mohawk (generally less than 2000 cfs due to semi-drought conditions). Sewage contains nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus that can promote harmful algal blooms (HABs) given the right conditions (16). Those conditions appear to have been met in early July when a short rainfall event was followed by low flow and warm weather. This slug of nutrients combined with warm water, low flow, and sunlight resulted in an algal bloom in the Schenectady Pool (above Vischer Ferry dam) between 8 and 10 July.

Algal blooms are stressful to the aquatic ecosystem and present major challenges for communities that use the Mohawk as a source of water because some algal blooms contain toxins. This is one of the reasons the NYSDEC is in the process of developing a plan to monitor and reduce the amount of phosphorus across the entire Mohawk Watershed (see 17). This process of regulating the Total Daily Maximum Load (TMDL) is focused on both point sources and nonpoint sources of phosphorus, including sewage from leaky pipes. HABs are a specific concern of the NYS DEC (web page), and addressing them is a focus of the water quality component of the Mohawk Basin Action Agenda (here).

There are also possible catastrophic events on the Mohawk that would impair water quality, and foremost among them is derailment of trains carrying hazardous material. The Mohawk has a long history as a transportation corridor. I recently wrote about the frequency, volume, and scale of crude oil transport by rail along the Mohawk (see this post). Volatile and explosive oil is still making its way down the Mohawk Valley on a daily basis. Derailment is not uncommon, and we need to learn from disasters that have occurred along rail transport lines. The 2013 Lac-Mégantic rail disaster in the Province of Québec resulted in a spill of 100,000 liters (22,000 gal) of oil in the Chaudière River, which forced closures of a number of water intakes (7). A year later the 30 km stretch of the river was still contaminated with oil despite the $16 m (cdn) cleanup effort (18).

Water quality on the Mohawk has improved significantly over the past half century. But we can learn from the past.. Whether potential issues are legacy, chronic, or catastrophic, we need to expect the unexpected and develop redundant systems that can continue to function in the event of impairment. Given this outlook, it would seem wise to maintain the Stony Creek Reservoir as a municipal water supply.

Summary. Municipalities across the Mohawk watershed use raw water sources that include river water, reservoirs, and/or groundwater. Given the potential complexities and threats to river water, it seems prudent to maintain and protect alternative sources when possible. Thus there is a practical argument that Stony Creek Reservoir should not be removed from the water portfolio of raw water for the Latham Water District. In any event, dam safety is critically important, and proper maintenance and investment in that Colonie Dam will be the ongoing responsibility of its owner unless the dam is removed

This and other Notes from a Watershed are available at: https://mohawk.substack.com/

Further Reading

1) Latham Water Department website. Website here.

2) Franco, J., 2020. Stony Creek is “Obsolete to Colonie” Spotlight News. Link Here.

3) Dumas, Patricia, 28 March 1990. Glycol problem crops up again. The Spotlight, page 3.

4) Onyon, Ashley, 7 May 2021. Failure at Amsterdam pump station dumped over one million gallons of sewage into Mohawk. The Recorder. Link Here.

5) Riverkeeper, Water quality summary for the Mohawk River. Web site here.

6) Willard-Bauer, E., Smith, J.A, Garver, J.I., Goldman, D., Newcomer, B., 2020. Enterococci levels in the Hans Groot Kill and Mohawk River, Schenectady, NY. In Garver, J.I., Smith, J.A., and Rodak, C. 2020. Proceedings of the 2020 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March 20, 2020, Volume 12, p. 63-68 (Link to paper here).

7) Lac Mégantic derailment disaster (summary)

8) Town of Colonie, Stony Creek Information meeting, Town Hall 20 April 2021. (link to past meetings, including this one here).

9) Office of the NYS Comptroller, 2018. Dam Infrastructure: understanding and managing the risks. (Pdf here).

10 ) Nearing, B., 2017. Hadlock dam legal battle ends after dozen years: 12 years after collapse, 80 property owners reach secret settlement. Times Union. Article here.

11) NYS DEC Dam safety regulations (DEC website here).

12) NYS DEC requirements for annual safety inspections for NYS Class C and B (High hazard and intermediate hazard) dams. (PDF here)

13) Garver, JI., 2020. Derailment: Rail corridor along the Mohawk River poses a special risk in the watershed. Notes from a Watershed. Link Here: https://mohawk.substack.com/p/derailment

14) The Department of public works, Division of Latham Water maintains a web portal HERE that has documents and FAQs about the Interconnect and the Reservoir.

15) SAVE COLONIE is a partnership for planning run by active concerned citizens. They have dedicated web pages HERE that are entirely focussed on the Stony Creek Reservoir. These pages include the RFP for the sale, and a number of news stories about the potential sale of the reservoir.

16) NY State Water Resources Institute, 2021. Harmful Algal Blooms (web page here).

17) Schnore, M, and Conine, A, 2020. Mohawk River Watershed modeling in SWAT. In Garver, J.I., Smith, J.A., and Rodak, C. 2020. Proceedings of the 2020 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March 20, 2020, v. 12, p. 52 (Link to paper here).

18) CBC News, 12 May 2014. Lac Mégantic rail disaster oil remains in the Chaudiére River. Web site here.

19) Garver, JI., 2020. Radioactive Fish 2: KAPL discharges of radioactivity well represented in sediment cores. Notes from a Watershed. Link here: https://mohawk.substack.com/p/radioactive-fish-part-2

20) Garver, JI, 2020. Leaking Landfill: Issues with the Town of Colonie Landfill on the banks of the Mohawk. Notes from a Watershed. Link here: https://mohawk.substack.com/p/leaking-landfill