Leaking Landfill

Issues with the Town of Colonie Landfill on the banks of the Mohawk

The Town of Colonie Landfill has been at the center of controversy for the last several years because it is close to the river, it has a toxic legacy, it is expanding, and it is being run by an out-of-state company. In 2011 the Town signed a 25-year contract with an out-of-state waste management company to run the landfill, and part of that deal involved expansion. Controversy surrounded the application process partly because the landfill has the potential to impair water quality in the Mohawk River.

The Landfill currently accepts municipal waste, but decades ago it accepted toxic waste that included solvents, hydrocarbons, and other waste from electroplating and car manufacturing industries. This material was dumped in an unlined part of the landfill, which is now leaking. Contaminants in groundwater are flowing into the Mohawk in the subsurface. Just as the permit was given for expansion in 2018, the discovery of PFOA in leachate complicated the picture. The latter point is important because the City of Cohoes, directly downstream from the landfill, takes its drinking water from the Mohawk. So this is the story of a landfill adjacent to a major waterway and the complications related to permitting and groundwater contamination.

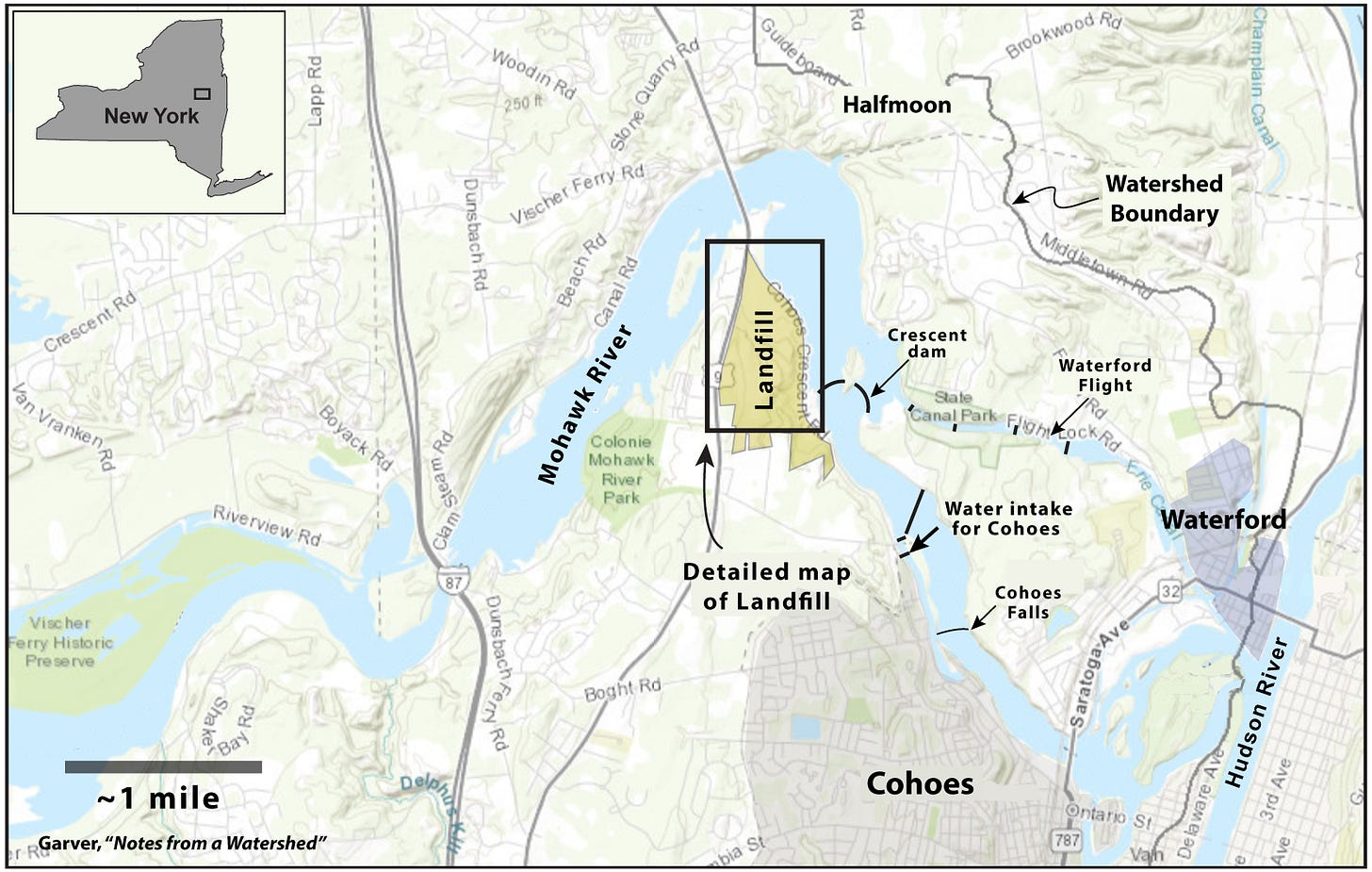

Location map of the Town of Colonie Landfill adjacent to the Mohawk River.

From a geological perspective, it is hard to imagine a worse place to site a landfill than the setting of the Colonie Landfill. The landfill is in loose unconsolidated glacial sediments that sit on fractured bedrock just a road’s width away from the Mohawk River. Both surface water and groundwater flow from the site to the River.

I had been aware of this developing story for years, but I found the issues tremendously complicated. Enlarging the landfill and the associated permitting process came to the forefront in early 2018 when the application for expansion was awaiting a decision by the DEC. Like many ongoing environmental stories, a stream of piecemeal information was linked by significant events such as applications, hearings, and lawsuits. I found I didn’t have a synoptic view of the situation, and so when new information emerged I didn’t have a framework to fit each piece into the bigger picture. Thus I felt the need to sit down and work out the geography, geology, a timeline, and central contamination issues to better understand the problem and how it pertains to water quality in the Mohawk River.

The privatization and expansion of the Town of Colonie Landfill is complicated because there are several interwoven issues. It involves different landfill cells (current or previous permitted working sections), groundwater contamination, and logistical and practical issues. There are thousands of pages of engineering reports, applications to the NYS DEC, hundreds of letters about the process, and lawsuits. So there is little chance that I can do the whole package justice. There are three underlying themes to bear in mind before we get started.

The first theme is the financial pressure of running local municipal landfills and the increase in privatization of those facilities. Landfills, drinking water, and wastewater are part of the central nervous system of municipal operations. Privatization of these systems – through contract or outright sale – may provide operational and financial relief, but there can be loss of control and an uncertain destiny when privatization decisions get made. The highest bidder and the community may have different goals that could be mutually exclusive, and this is where the danger lies in this process. At the end of 25 years, the contractor leaves but the Town owns the land, the waste, and future problems.

The second theme is dealing with toxic legacies and past practices in landfills. Landfill design has changed dramatically in the past few decades, in part due to well-designed liners (below the fill), capping material (above the fill), and collection systems for landfill gas and leachate. There is also a better appreciation for what should and shouldn’t be dumped into the ground; this is reflected in the permitting process. One can wonder: What were they thinking when they dumped liquid toxic waste in an unlined pit in loose sediment next to the River? One can only wonder what they will be thinking of our modern practices some 50 or 100 years in the future.

The third theme is centered on the larger question of total permitted landfill space regionally, which in this case would be the Capital District of New York. Note that the landfill equation in NY State has changed dramatically in the last few decades. In 1988 there were 227 municipal solid waste landfills in NY. Today there are only 27 [23]. Thus space in landfills has become valuable. The most useful landfills are close to municipalities, while also out of the way in geologically and geographically appropriate settings. But the equation that includes tipping fees and trucking costs means that in some cases it is cost-effective to move waste great distances if landfill space is not available locally. Thus there may be competition between municipalities with disappearing landfill space downstate (NYC) and the more rural cities and towns of Upstate New York [11]. As rural as Upstate is, we still have active municipal landfills that are in urban settings. This landfill space is valuable to local municipalities, and conflict may arise if that space is consumed by others with deep pockets.

Privatization of the Colonie Landfill in 2011

For decades the Colonie Landfill appears to have been run by the Town of Colonie in a normal way: trash was collected, tipped in the landfill, and the wheels turned. In the early years (1968-1972), toxic waste was dumped in what is now an inactive part of the landfill (now considered a cell) that was capped in 1983. Although the Town’s operating permit extended to December 2017, financial issues prior to 2011 forced the town to look at privatization as a solution.

The landfill privatization agreement was finalized in 2011 with Waste Connections, a private contractor that now runs and profits from landfill operations [see Further Reading 4]. At the time the privatization was a 25-year deal that resulted in the town getting $23.8 m upfront and then $33.5 m over 25 years. Incentives were included to get NYS DEC permission for expansion [5]. This expansion requirement was important for both parties (and it’s hard to see how the privatization agreement could have worked without expansion).

The privatization deal changed the equation for the landfill. From the mid 1990s to 2011 – when the Town ran the landfill - annual tonnage was reported to be between 150,000 and 200,000 tons annually. After the 2011 Waste Connection agreement, tonnage more than doubled to over 400,000 tons a year [5].

There is a lot of money in trash. Waste Connections (NYSE - WCN) is in the waste management sector. They have annual sales of $4.92 billion and operate widely in the US and Canada. They collect, transfer, and dispose of waste, including municipal trash. The also have recycling services [1]. Earnings are currently expected to grow by over 15% annually, but the company has a high level of debt [2]. Company headquarters are in The Woodlands, Texas, and Vaughan, Ontario [3]. Waste Connections has a subsidiary named Capital Region Landfills that is handling the daily operations of the Colonie Landfill.

One strategy that has been successful for the company is taking on waste management for municipalities under contract. Under some privatization schemes companies are contracted to collect waste and operate landfills that are owned by municipalities. In this sort of arrangement, one potential issue is that the out-of-state contractor may not have the same environmental perspective as local towns and villages near landfills. Another potential issue is that once contracts are over, the company can close up shop and leave town, but the local municipality owns the landfill, its contents, and any future problems.

Landfills charge by the ton, and “tipping fees” have risen dramatically. The Environmental Research & Education Foundation (EREF) maintains a database of tipping fees and trends in the US [10]. Their last summary shows that fees continue sharp year-over-year increases (3-5% annually), but it also shows regional fee rates and variation in these fees. Nationally the average tipping fee is $55/ton. But rates vary dramatically: the most expensive tipping fees in the country with large population centers are in the Northeast (average of $67/ton), with Rhode Island, Delaware, and New Jersey leading the way (fees between $82 and $110/ton). Alaska leads the nation at $155/ton [10].

Recall that there has been a steep drop in landfill space in NY State; this is related to the increase in tipping fees. The average reported tipping fee in NY State in 2018 was $68/ton, but this fee varies widely even across the state [10]. The spatial variation of tipping fees and the high total cost in the US has lead to garbage arbitrage: railcars and trucks move trash to low-fee landfills. This happens every day in the Mohawk Valley as trains carry trash westward. If you are looking for cheap landfill space, look no farther than Kentucky where you can unload for an average of $29.82 a ton.

Geology and old landfill issues

The engineering report for the expansion reveals that both surface water and groundwater drain to the Mohawk River [22]. The site is underlain by glacialacustrine silts and clays, with glacial till sitting on bedrocks of sandstone and shale. The till has discontinuous permeable sand layers that are as thick as 5 ft. The engineering report identifies three water-bearing zones in this sequence (upper, intermediate, and lower). Groundwater in all three layers flows eastward to the Mohawk River. The upper zone is unconfined, and the lower two are confined [22, p. 11].

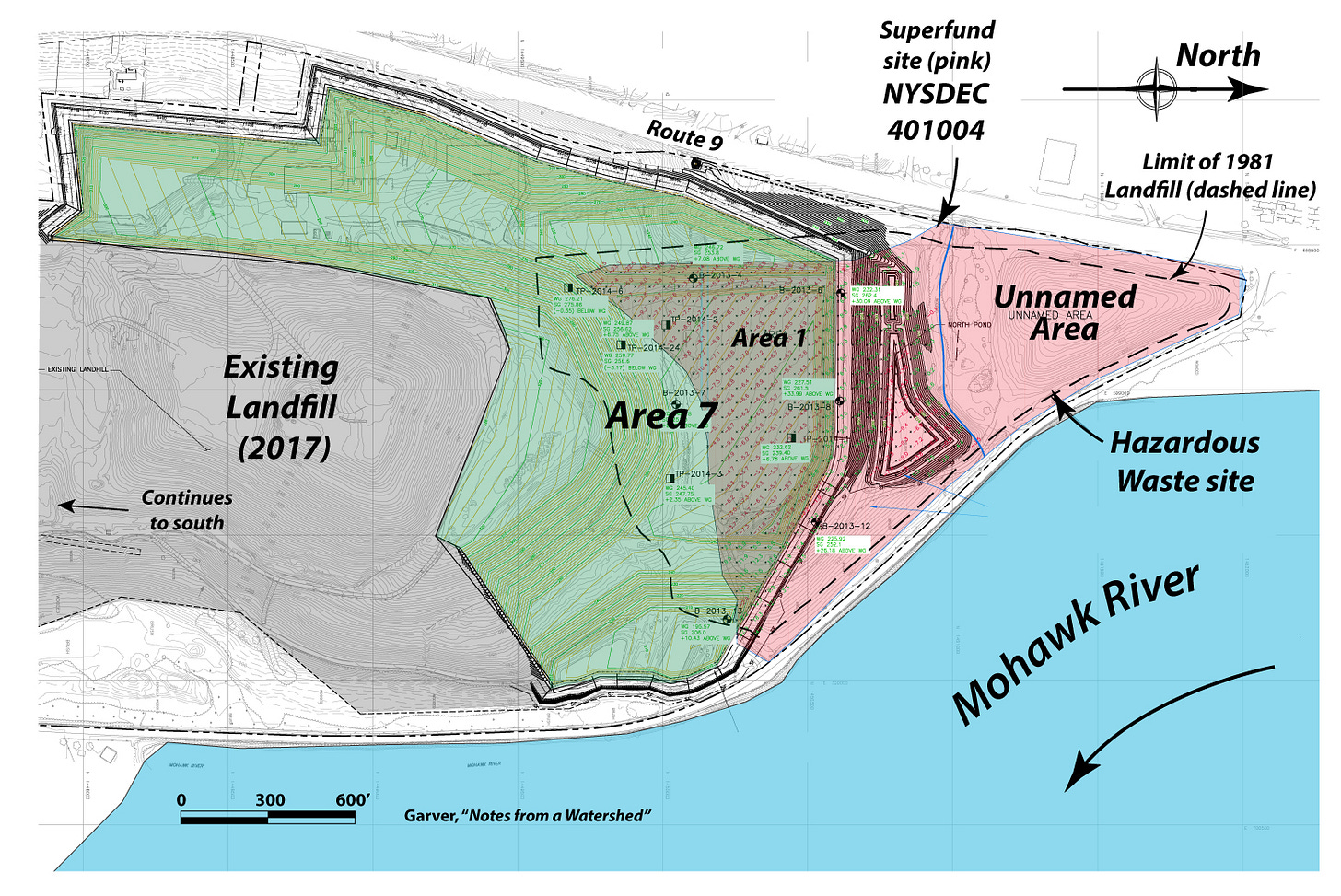

Map of the landfill area showing the active existing landfill (as of 2017), the expansion of Area 7, and the unnamed area (#401004). Note that the NYS DEC Superfund site includes the Unnamed Area and Area 1 (both pink above). Area 7 as proposed above (what was permitted was slightly different) would sit on top of part of #401004. Map is modified from the 2017 Area 7 Development application (this is from Figure 1-2 made by Cornerstone Environmental) [13].

“Unnamed Area”

An old closed part of the landfill is a major problem because it is leaking. This unlined part of the landfill has a buried toxic legacy that qualifies it as a NY State Superfund (site #401004). This site is a ~50 acre parcel on the northern end of the landfill complex, and its consists of several parts, but the unnamed area has some of the toxic chemicals that are a major concern. The unnamed area is referred to as the unnamed area so often in technical documents it is remarkable that no one has yet named it. It will henceforth be referred to as the Old Unlined Toxic Landfill. But there appears to have been confusion as to the extent and boundaries of the hazardous waste site.

In the Final EIS (FEIS), this issue is clarified and the early mistake was acknowledged: “It was Town’s initial understanding that the areal extent of the Class 3 inactive hazardous waste site was limited to the Unnamed Area. The 1.9(g) Report [see ref 13 below] identifies the limits of the Class 3 Site. These limits are based upon NYS GIS inactive hazardous waste site information, which appear to be consistent with historical reports and landfill plans, and include the Unnamed Area and a portion of Area 1.” [see p. 19 in 14]. This matters because Area 1 is part of the Class 3 site and this capped fill is to be overlain by expansion fill of Area 7.

Old Unlined Toxic Landfill received toxic waste mainly between 1968 and 1970, and this area and Area 1 were capped and closed in 1983 after a Consent order from the DEC [21]. Recall that part of that area (Area 1 in map above), is slated to be covered by new waste in the expansion plan (Area 7). The toxic waste of concern came from the Watervliet Arsenal, Norton Company, Ford Motor Company, and Troy Belting and Supply. About 85,000 tons of additional municipal waste was also dumped in the site [13].

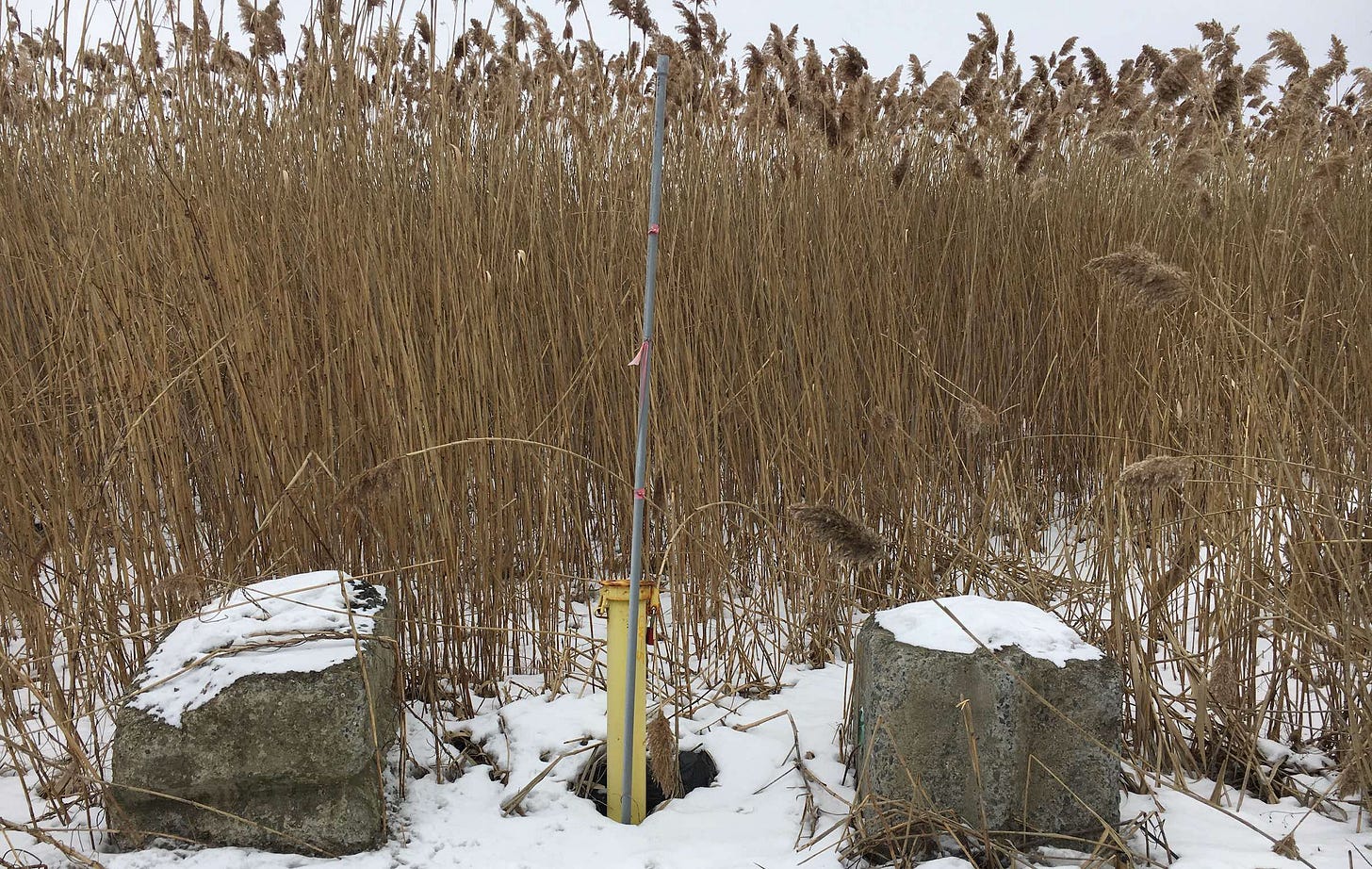

The first line of defense between the Old Unlined Toxic landfill and the Mohawk River: the monitoring well. This and other monitoring wells along the old landfill are used to sample contaminated groundwater adjacent to this part of the unlined landfill, now capped and overgrown (Photo JA Smith, 16 Feb 2020).

Material dumped include: chromium hydroxide sludge; solvent-based phenolic and urethane sludges; spent paint with waste and solvents; and trichloroethylene [21]. Some of this material has leaked and is in groundwater, and if the engineering reports are correct, that contaminated plume is drawn into the Mohawk. The monitored groundwater contains hydrocarbons and heavy metals, and the primary contaminants of concern found in the groundwater are benzene, toluene, xylene, lead, and chromium [21]. One thing missing from the dumped inventory and from the groundwater monitoring is PFOA. The DEC notes:

“The inactive portion of the landfill is impacting local groundwater with levels of hydrocarbons and heavy metals, but the contamination is not conclusively attributable to the hazardous waste that was disposed at the site. The site is currently monitored as part of the Town of Colonie’s solid waste facility operation's permit. [21].

Groundwater is not the only concern. In December 2015 surface water with leachate reportedly ran off the site and into the Mohawk River. The NYS DEC issued a Notice of Violation (NOV) and a $40,000 fine for the violation related to stormwater quality and reporting requirements [25].

Expansion – Area 7

In 2014 the application process was initiated and expansion into Area 7 was proposed. The expansion (see green area in Landfill map) would allow for 20-25 years of additional landfill life by significantly increasing permitted space. Area 7 makes efficient use of space by partly covering or dovetailing with older parts of the landfill, including recently permitted areas as well as old capped areas (Area 1). The application and the process were complex, but there are a few critical issues. One is that the proposed expansion would increase the height of the landfill considerably, a second is that new fill would be located close to the Mohawk (~100 ft), and a third is that some of the area would cover Area 1, part of the Class 3 Hazardous waste site. Naturally there were broader issues at stake in the application process, including the suitability of the siting of this landfill on the banks of the Mohawk, odors and noise of an urban landfill, damage to the viewshed, and questions about privatization.

By mid 2016 the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) was released for comments, and in the Spring of 2017 the process was well underway and the 1.9(g) Report was released [13]. §360-1.9(g) is a State requirement for landfill permitting that requires discussion of impacts on adjacent (150 ft) inactive hazardous waste disposal sites [24], which in this case was central to the expansion plan (it was partly going on top of an inactive hazardous waste site).

Public comment on DEIS

The Draft Environmental impact Statement (DEIS) for the Proposed Area 7 Development, the engineering studies, and other information about the expansion were up for public comment late in August 2016 with comments due in October. The amount of material submitted as part of the application was enormous – stakeholders had to deal with over 3500 pages of material in short order. The comments themselves are nearly 1000 pages.

Kevin Tollison, Town supervisor of the Town of Halfmoon (across the River from the landfill), wrote: “The voluminous application and supporting documentation is too cumbersome to review and analyze within a thirty-day period” [see p. 29 of 14]. While the letters cover a number of topics, most are against expansion and they focus of issues of odor, noise, traffic, and effects on the Mohawk River.

A significant number of comments are focused on the Inactive hazardous site and the effect that the expansion might have on contamination from that site. The EIS notes that the inactive site is a NYSDEC Class 3 site, which therefore does not pose a significant threat to the environment or the public. But, as noted, it requires constant monitoring. If that site becomes a Class 2 site, which would pose a threat to public heath and the environment, then the expansion plan would hinder remediation.

A good way to evaluate the comments and the response is by combing through the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS), in which comments and responses are parsed into specific topics [15]. Let’s take a look at a few key comments that relate to groundwater and the River (letters are ascribed to individual “Commenters” and they are numbered). One noted:

“Taking an inactive hazardous waste site that currently is classified a Class 3 site due to undocumented exposure pathways and handling it in this way in this environment will expose public health and the environment to unnecessary risks with the almost certainty that it will become a Class 2 site as a threat to public health and the environment.” [p. 18 of ref 15, commenter 51].

In addition, that comment added:

“Even the original DEIS [Draft Environmental Impact Statement] has firmly established at this point that groundwater under the active landfill portion as well as the inactive hazardous waste site portion of the landfill is contaminated above standards, all the subsurface water bearing units below the landfill and hazardous waste site flow into the Mohawk River. On top of this, the additional studies recommended in the 1992 URS Phase II Investigation Report the magnitude and potential impacts to the Mohawk River were never conducted.” [15 see p. 13, commenter 51].

There were many comments about contaminated groundwater and how that groundwater may affect the River. The response was that the new landfill cover will reduce infiltration and hence ground water, and that no contamination had been detected in the Mohawk River.

How might the new landfill layer (north part of Area 7) affect the underlying contaminated site (Area 1)?

“The groundwater within the unlined old waste mass, its placement on the highly permeable alluvial layer, and the probable communication with the nearby Mohawk River is an environmental disaster, which is preventable. The additional load of the new waste over the unlined waste mass will cause immediate increase in pore water pressure within the old unlined waste. This increased pore pressure will dissipate by drainage through the alluvium layer and ultimately into the river. This will occur for years as the weight of the new waste mass increases.” [15, commenter 41].

Finally, two commenters (53 and 102) asked why there had been no PFOA testing of the contaminated groundwater. The response in the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) was, frankly, a little unsettling. In the FEIS it is noted:

“There is no evidence that Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) was disposed of at the site. Historic waste disposal areas (i.e., waste deposited prior to current regulations) at this facility and others are monitored for known contaminants to determine if remedial actions are necessary to protect human health and the environment.” [see p. 53 in ref 15].

In addition, it is implied in the PFOA response (in the FEIS) that if there were a PFOA problem, the City of Cohoes would have discovered elevated levels of PFOA in their drinking water because they take water directly from the river, downstream of the landfill [15]. The City tests its water quarterly, and in general PFOA in not detectable. However, a water sample from Cohoes taken in March 2016 had PFOA levels of 2.3 ppt (parts per trillion): the EIS noted this sample was well below the limit of 100 ppt (at the time) [15, p.53]. But the regulatory environment surrounding PFOA and PFOS has been evolving rapidly and dramatically in the past few years.

New York State has been at the forefront of advancing tight regulation of PFOA and PFOS in drinking water, in part in response the problems at Hoosick Falls. In 2019 NYS signaled that is was poised to lower the PFOA/PFOS limit in drinking water to 10 ppt, which will be the lowest in the nation [see ref 16, 20]. Late in 2018, the Drinking Water Quality Council (under NY DOH) recommended Maximum Concentration levels (MCL) of 10 ppt for both PFOA and PFOS and 1 part per billion for 1,4-Dioxane [A].

In July 2019 these recommendations for the MCL of PFOA, PFOS, and 1.4 Dioxane were accepted by NY Health commissioner Howard Zucker [16]. Clean water advocates like Julia Li of the Natural Resources Defense Council suggest that the combined MCL of PFOA and PFOS should be as low as 2 ppt [19]. But there is a more important issue here about PFOA/PFOS monitoring at the landfill: if we wait until it is detected in the Cohoes drinking water supply, we have failed in a spectacular way.

PFOA in leachate – early 2018

Late in 2017, Riverkeeper joined Waterford and Halfmoon in opposition to landfill expansion [8]. Leading the effort for Riverkeeper was John Lipscomb, Captain of the Riverkeeper patrol boat and environmental advocate. At the time Lipscomb noted that monitoring of leachate and stormwater from the landfill was an important objective and that emerging contaminants are a concern.

In 2018 opposition to expansion of the landfill was strong, and the permits related to expansion were being considered by the NYS DEC. In March of 2018, Lucas Willard of WAMC reported that the towns of Waterford and Halfmoon had partnered with Riverkeeper to analyze runoff from the landfill and water samples from the Mohawk for contamination [6].

Water samples were taken for analysis by the town of Waterford, Town of Colonie, and Riverkeeper. Water taken from storm drains between the landfill and the River and stormwater outfalls had elevated concentrations of PFOA (68 to 519 ppt), which were much higher than those reported from the adjacent Mohawk (1-3 ppt). As noted, the level of these cancer-causing contaminants in the River is critical to the City of Cohoes, which draws its water from the Mohawk just downstream from the landfill [6].

Expansion Approval – April 2018

Early in 2018 the operating permit for the landfill had expired, but reduced operations continued under an extension granted by the NYS DEC [17]. In April 2018, four years after initial request, the NYS DEC granted the Town of Colonie approval to expand the landfill in Area 7. As planned, this expansion allows for another 20 years of use (until 2038) [23]. The permit had a number of requirements for environmental monitoring, and it required a 500 ft setback from the Mohawk River [9]. The permit allows dumping of ash residue from incineration of municipal waste from facilities that have NYS DEC permits, and thus it would seem that out-of-state ash wastes are not permitted.

Waterford town supervisor Jack Lawler was quoted by the Troy Record at the time [9] as saying:

“The DEC’s decision places the Mohawk River at great risk of pollution and contamination from PFOA (Perfluorooctanoic Acid) runoff from the landfill. We intend to initiate litigation in the very near future to reverse the denial of the request for an adjudicatory hearing and the issuance of the permit itself.” [9]

Lawsuit and Legal Limbo

In May of 2018, The towns of Waterford and Halfmoon filed a lawsuit challenging the DEC decision because their request for an adjudicatory hearing on the review process was denied. The suit named the NYS DEC, the Town of Colonie, and Waste Connections [18]. Concerning the lawsuit, Kevin Tollison, town supervisor for Halfmoon was quoted at the time by WAMC as saying:

“You know, there’s a lot of technical arguments of why this shouldn’t be. And if this was a new application for a landfill near a river, it wouldn’t even be considered because the regulations say that you can’t do that any longer.” [18]

In January 2019 the lawsuit was dismissed with a ruling that Halfmoon and Waterford did not have standing – in part because they lived more than 500 feet from the landfill. Spotlight news, who first reported the ruling, noted that:

“Acting Supreme Court Judge Debora Young, in her one-page ruling, said that according to the New York State Environmental Quality Review Act, for a party to have standing it must allege “specific environmental injury which is in some way different than the public at large.””

Jack Lawler, supervisor of Waterford, has been vocal in his opposition to the Landfill. At the time of the decision in January 2019, he is quoted [12] as saying:

“It’s pretty obvious we would strongly, respectfully, disagree with Judge Young’s rationale. It’s hard to understand how the people who can see the landfill, and smell the landfill and hear noise from the landfill, have less standing than the general public who don’t experience any of those things.”

In early 2019 the decision that Waterford and Halfmoon did not have legal standing was appealed by the plaintiffs. However, since then the story seems to have dropped of the news feed, so I contacted Jack Lawler and asked him where the case stands, nearly a year after appeal.

He told me that the final paperwork for the appeal was submitted in late August, and the initial deadline for the State was 20 November 2019, but the DEC was granted three more months to submit a succinct brief, and the final deadline for submission is Tuesday 25 February 2020.

Perhaps we will have a sense of the legal situation some time in 2020. Meanwhile careful and continuous monitoring is critical to ensure that the water quality in the Mohawk is not compromised.

This and other Notes from a Watershed are available at: https://mohawk.substack.com/

Further Reading

[1] NYSE: WCN - Waste Connections Stock Price, Forecast & News, Feb 2020.

[2] Simply Wall Street – Summary of Waste Connections.

[3] Waste Connections, summary. Wikipedia

[4] https://wasteconnections.investorroom.com/quarterly-results?item=10

[5] Rick Karlin, Times Union. July 2019. “Colonie landfill operator buys nearby property”

[6] Lucas Willard, WAMC, 22 March 2018. “Opponents seek further testing as DEC considers Colonie landfill application.”

[7] First report of PFOA from water samples in Times Union, but covered by WAMC in Nov 2017.

[8] Lucas Willard, WAMC, 25 October 2017. “Riverkeeper Joins Neighbors To Fight Landfill Expansion”

[9] Glenn Griffith, The Troy Record, 10 April 2018. “DEC gives town of Colonie approval to expand landfill”

[10] EREF 2019. Analysis of MSW Landfill Tipping Fees, April 2019 (revised October 2019). Environmental Research & Education Foundation (EREF).

[11] Robert Downen, Times Union, Feb. 19, 2017 (Updated: Nov. 15, 2017). “Waste materials from outside region increasing at Colonie landfill - Town of Colonie's privately run landfill takes thousands of tons of "alternative" material and ash from beyond region”

[12] Spotlight news. 30 January 2019. “Judge tosses lawsuit against Colonie landfill expansion (updated w/appeal forthcoming).”

[13] 19g Report. Town of Colonie Landfill. Area 7 Development application.

[14] Area 7 – FEIS Appendix K – Comment letters

[15] Final EIS for the Colonie Landfill including response to comments.

[16] AP news, 8 July 2019, “NY Sets PFOA limit”

[17] Brian Nearing, Times Union,2 Feb 2018. “As Colonie dump close to full, waste diverted to Rensselaer - But Rensselaer dump has own opposition; Colonie waiting for decision to keep Route 9 landfill open”

[18] Lucas Willard, WAMC, 18 May 2018. “Capital Region Landfills Under Scrutiny”

[19] Allison Dunne, WAMC, 5 Feb 2020.“Activists Pan A Proposed NYS Provision For Recommended PFOS, PFOA Levels”

[20] Amendment of Subpart 5-1 of Title 10 NYCRR (Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs)

[21] NYS DEC Environmental Site database for the State Superfund Program. Site #401004

[22] See Section 2.4, Site Geology in Area 7 Engineering Report Revision – July 2016 by Cornerstone Environmental - Document available from “Area 7 Documentation” from the Town of Colonie Landfill main website. here:

[23] 2018 Office of the NY State Comptroller, December 2018 “Local Governments and the Municipal Solid Waste Landfill Business”.

[24] Chapter VI - Solid Waste Regulation (from Knauf Shaw Law)

[25] Spotlight News, 3 March 2019, “DEC fines Colonie, landfill operator” .