Rebeavering the Mohawk

History of beavers and how they are reclaiming their role in the Mohawk Watershed

Throughout the history of the Mohawk Watershed, our relationship with beavers has been complex, but it may be time to recognize their role as "eco-engineers" capable of mitigating the impacts of climate change on watershed hydrology. Beavers have long influenced the evolution and history of the Mohawk Watershed, but the growing human population and high global demand for beaver pelts led to the near-extinction of beavers by the mid-1800s. Loss of beaver dams and wetlands caused rapid and dramatic environmental changes that altered hydrologic flow and sediment pathways. It was not until the early twentieth century that this trend began to reverse, and today New York State has more beavers than at any time in the past 300 years. Rebeavering the Mohawk Watershed - and New York State generally - has brought significant challenges due to human-beaver conflicts, but it also provides us with a golden opportunity to harness beavers’ natural ability to slow water flow and trap sediment at a time when extreme precipitation and erosion have disrupted the balance of rivers and streams.

Beavers build dams and wetlands that slow water flow and capture sediment, and thousands of these dam complexes across the Watershed could reduce the impact of flooding and improve water quality. Perhaps no one has done more to elevate the modern profile of beavers than author Ben Goldfarb in his 2018 book “Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter,” which is a story of the movement to “rebeaver” America, in part driven by a better appreciation of beavers as ecosystem engineers, especially when it comes to water and wetlands [1]. “They’ve turned seasonal trickles into perennial streams, revived trout populations, and captured contaminants better than many wastewater treatment plants. They’re the ultimate keystone species, stout miracle workers that can address an array of environmental ills.” [2].

Encouraging beavers to build more wetlands could offer sustainable solutions for "slowing the flow" in response to extreme precipitation and drought - the weather whiplash we’ve seen over the past few years. These industrious animals and their dam complexes could become central to climate action strategies aimed at preserving freshwater ecosystems and managing the effects of climate change [3].

This watershed note explores the historical role of beavers in the Mohawk Watershed of NY State. This topic is involved because beavers have long been central figures in the history and economy of NY and the Northeast [4]. We are in an interesting time because beaver populations are increasing, as are total rainfall and extreme rainfall events. However, more beaver dams mean problems associated with flooded private lands, especially agricultural lands. It also means we need to develop some tolerance to the inconvenience of flooding, and outburst floods from failed beaver dams if we are going to coexist happily with beavers.

Here we start at the beginning to frame the overall population of beavers in NY and how they modified the landscape following deglaciation, and then how they have recovered from near-extinction in the wake of trapping and the fur trade of the Beaver Era (c. 1600-1800) [7]. A previous post examined modern land use changes and how beavers are already well established and doing their part to transform the watershed and that much of their effort and population growth appears to be on less productive farmlands that are slowly being reforested (here - [5]). Let’s dig into the history of beavers in the Mohawk Watershed.

Part of the cover image of “Black Gold: The story of the beaver in New York State”by Gardiner Bump and Arthur Cook (here) [6]. This sketch was made by Clayton Seagears, who illustrated most of that bulletin. By 1940, beavers were well enough established in NY that the Division of Game actively managed them for fur harvesting, but this still included statewide relocation efforts with the “Beaver Bus” that transported live-trapped beavers to other less populated parts of the State.

Historically, beavers have played a key role in the development and economy of the Mohawk Watershed. Early in the Colonial Era they were targeted for the fur trade, then the Mohawk became a central avenue for trade, and much of that trade involved the transport corridor for beaver pelts from the west. To get a sense of perspective, let’s start before the Colonial Era - sometimes referred to as the “Beaver Era” (c. 1600-1800) [7]) and try to get an idea of the natural setting before the onset of European-driven trapping and the eventual near-extermination of beavers in NY.

Prehistoric beavers. There is direct evidence that beavers have been in the Mohawk Watershed since the end of the ice age, and those early beavers advanced to the edge of their ecological comfort zone as continental ice sheets retreated and vegetation was reestablished. In North America, the fossil record indicates that the family Castoridae first appeared in the Late Eocene, the genus Castor first appeared in the Late Miocene at about 7 Ma (Castor californicus), and our friend Castor canadensis (modern North American beaver) first appeared in the late Pleistocene [8]. Thus dam-building and watershed alterations by this genus have likely been ongoing in North America for the last 7 million years - before, during, and after the repeated advances and retreats of ice sheets [8]. Full glaciation and ice scour means that in NY, we really have a possibility of seeing the paleontological record and landscape modification only since ice retreat following the Last Glacial Maximum at ~25,000 years ago because earlier records have been mostly scraped away by the most recent ice advance.

Giant Beavers (Castoridae ohioensis), which were swamp dwellers rather than dam builders, co-existed with Castor canadensis before Giant Beavers disappeared in the late Pleistocene megafauna extinction about 10,000 years ago [9]. There is an interesting connection here with the last of the Giant Beavers and the Mohawk Watershed. Fossils of Pleistocene Giant Beavers are common in deposits of that age around the early meltwater-affected Great Lakes [10]. A nearly complete skull of a Giant Beaver was excavated in 1845 in the canal works in Clyde NY (between Cayuga Lake and Lake Ontario) and the deposit also contains gnawed wood that is thought to have been from Castor canadensis [11,12]. James Hall, who first described the occurrence, suggests that the deposit was at the same position as “Ridge Road,” which represents deposits along the shoreline of Glacial Lake Ontario (Lake Iroquois); the glacial lake was 150-200 feet higher than the modern lake in this location [11].

In general the youngest dated fossils of the Giant Beaver are from Ohio and New York, and the youngest dated sample is the specimen from Clyde NY, just to the west of the modern Mohawk Watershed [10, 9]. However, at the time of deposition, this site was part of the much larger Iromohawk watershed, so in a way it is still part of the early history of the Mohawk Watershed. The Clyde skull was recently dated at ~11,750 cal yr BP and is recognized as the youngest dated Giant Beaver in the fossil record [9,10]. Recent analyses of stable isotopes from the bones of Giant Beaver confirm that they relied on aquatic vegetation for food, and that they did not use trees for nutrition, food, and construction as their smaller dam-building cousin, Castor canadensis, does [9].

The oldest direct evidence of modern beaver (Castor canadensis) activity in the Mohawk Watershed comes from deposits in the city of Cohoes along the lower Mohawk River (near the confluence with the Hudson River) where deep potholes in the former river channel filled with organic material and provide a record of major drainage reorganization and rapid environmental change during deglaciation. In 1871, the Cohoes Mastodon (Mammut americanum) was discovered in a deep, mud- and muck-filled pothole in an old riverbed above the modern Mohawk during the construction in 1866 of a building for Harmony Mills [13]. The excavation was overseen by James Hall (the same person involved with the Giant Beaver fossil), then the NY State Paleontologist, who noted that the mastodon remains were buried along with fragments of beaver-gnawed wood [13].

More recent study of similar material from those potholes was undertaken by Norton Miller of the NY State Museum and Carol Griggs from the tree-ring laboratory at Cornell [14]. They discovered a beaver-chewed 40-year-old balsam fir log that was then radiocarbon-dated at 12,470 ± 95 cal years BP, making this the oldest definitive evidence of the establishment of modern beavers in the Mohawk Watershed. This log is about 400 yr younger than the date of the Cohoes Mastodon, and slightly older than the Castorides ohioensis from Clyde NY (the Giant Beaver discussed above). Given the paleoecology of the deposits - including the Mastodon remains - these beavers were initially living in a boreal forest environment dominated by white spruce, balsam fir, pine, and tamarack that had just been established following retreat of the ice front from in this area [14,15].

These ancient beaver logs were deposited during the Younger Dryas cold reversal (~12,900 and 11,700 cal yr BP) that followed the catastrophic release of meltwater from Glacial Lake Agassiz, although the cause of the abrupt period of cooling remains controversial [16]. The catastrophic release of Glacial Lake Iroquois, the larger and earlier version of Lake Ontario, which drained through the Iromohawk River into the Hudson, occurred slightly earlier at ~13,300 cal yr BP. Regardless of the specific timing, these beavers apparently were active in the Cohoes Falls area following the drop in Glacial Lake Albany while a boreal ecosystem had been established. Fossils of mammoths, mastodons, musk ox, and caribou have also been recovered from similar deposits in this part of the state. Pollen records from deposits of this age suggest that the environment was not ideal for beavers because the ecosystem lacked alder, aspen, willow, and other herbaceous vegetation that beavers prefer [14]. Nonetheless, from the paleontological record of these important deposits, Norton Miller concludes: “Beavers were a part of the Younger Dryas ecosystem” [17], and thus beavers have worked and caused change in the landscape of the Watershed for the ten millennia since.

Pollen records in deposits in the lower Mohawk Watershed show that vegetation transitioned quickly after the Younger Dryas and that the environment likely became much more advantageous and preferable to the beaver diet [14]. Undoubtedly this environmental change ushered in a wildly successful period of beaver proliferation and dam-building that modified the landscape by trapping sediment and building fertile flatlands in the network of tributaries that fed the Mohawk in this now ice-free landscape.

The long-term effect of landscape modification and sediment accumulation in post-glacial and pre-colonial beavers dams in the Mohawk and Hudson watersheds was profound. This impact was recognized in the early to mid 1930’s by Rudolf Ruedemann and WT Schoonmaker of the NY State Museum while mapping geologic quadrangles in the Cohoes, Troy, and Schuylerville quadrangles in the Capital District of NY State [18]. They suggested that a number of broad alluvial plains, now valuable and productive farmland, resulted from the timeless work of beavers building dams that captured sediment and filled valleys over thousands of years. Hence they argue that beaver dams are “geologic agents,” and conclude that over the millennia since deglaciation, beavers “have accomplished an enormous amount of aggrading work and are important physiographic agents” [18]. In this instance, aggrading is accumulation and build-up of sediment over the entire Holocene in what are now broad, flat fertile plains across the landscape - areas now covered with roads, villages, and farms. So many of our most productive farmlands were created by beavers. This process would all come to an end in the seventeenth century with the arrival of Europeans and the fur market.

Fur Era or the “Beaver Era”. Widespread beaver activity changed with the arrival of the Europeans in the 17th century, led in part by the arrival of Henry Hudson in 1609. In his book Fur, fortunes, and empires: the Epic History of the fur trade in America, author Eric Jay Dolin noted that “The dawn of the seventeenth century was a horrible time for beavers” [7]. Dutch merchants were granted trading rights in 1614, and in 1618 they had established a treaty with the Iroquois on the Norman’s Kill near Beverwijck (translated as “Beaver District” - now the City of Albany), which was soon a key fur trading post [19,20]. This marks the onset of the Beaver Era and of profound changes to the landscape in the Watershed. Perhaps this time should be called the “end of the Beaver Era".

Once trapping and trading were established, the increase in the annual take of beaver was rapid and dramatic. Dutch author Vanderdonck wrote in 1642: "That in the New Netherlands, and in the adjacent country, about eighty thousand beavers have been killed annually during my residence of nine years in the country." [21]. Many of those beaver pelts came out of the Mohawk and Hudson watersheds, and a transit hub for furs was Beverwijck. The virtual extermination of the beaver followed, as did the Beaver Wars. By 1650 to 1660, locally-derived furs were scarce to non-existent in this part of NY [32, 22], and trapping shifted west [7]. Thus the Mohawk entered a new phase of watershed development because for the first time since deglaciation, beavers and their dams were no longer part of the ecosystem: they were gone, all of them. All that trapped sediment, muck, and peat behind abandoned beaver dams was available for erosion and transport downriver and into the Hudson River estuary.

In this short and dramatic new watershed regime, sediment and organic carbon were liberated from abandoned beaver meadows, and presumably flooding was facilitated by faster, flashier streams that undoubtedly carried more sediment [23]. We don’t have a direct record of this era in the Watershed, and this remains a key area of scientific research that is virtually unexplored. But the flush of sediment from incised abandoned beaver ponds has been recognized in the downstream and offshore sedimentary record downriver in NY and New England. Johan Varekamp at Wesleyan University and colleagues studied sediment cores from western Long Island Sound, and this work showed an increase in sediment and particulate organic carbon starting in the late 1600’s that coincides with the main period of fur trapping and beaver dam abandonment and removal in NY and New England between 1640 and 1760 [24]. This accidental watershed experiment would start to unwind in the early twentieth century when beavers were reintroduced to NY State.

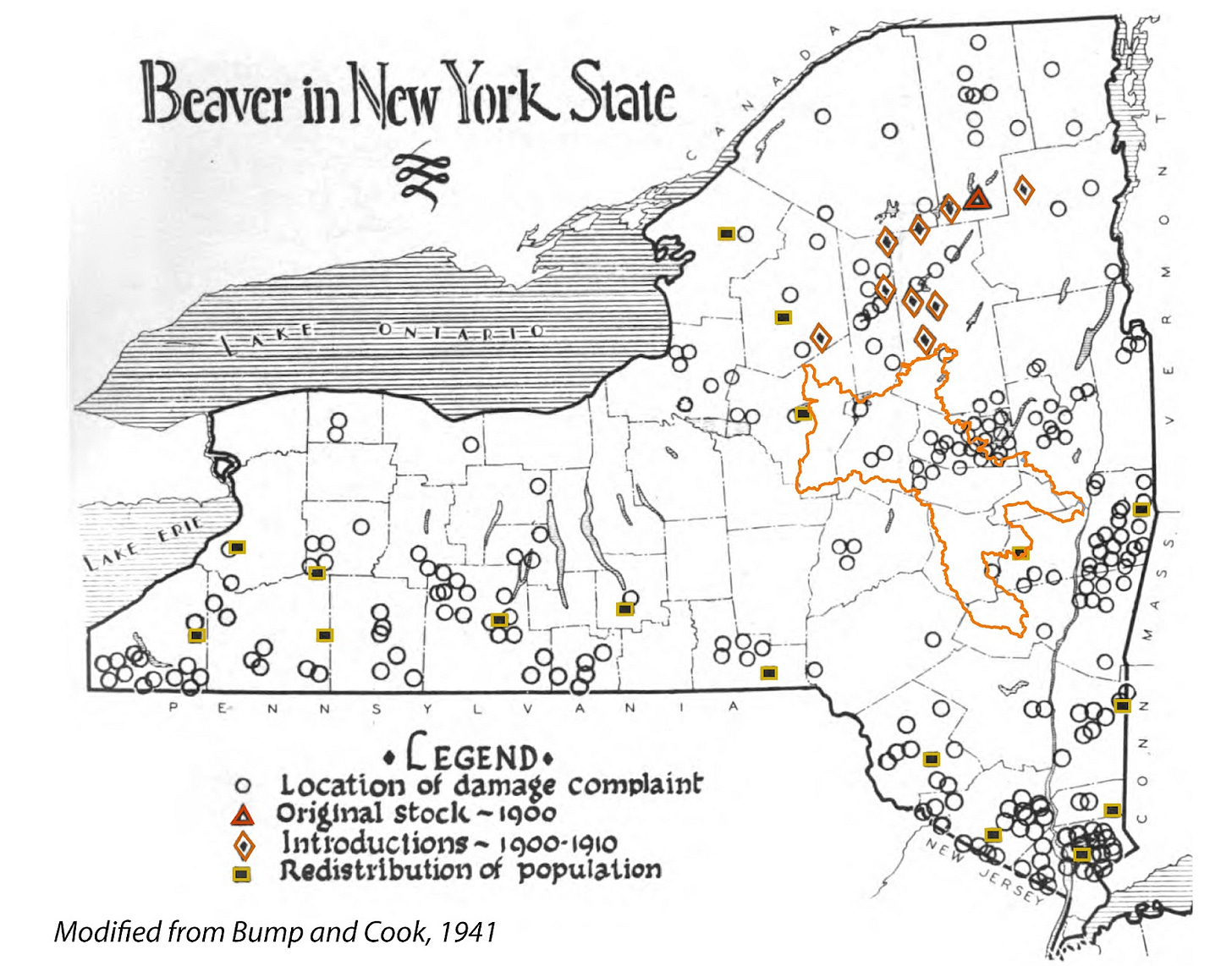

Rebeavering New York started in the beginning of the twentieth century, and the last 125 years or so have been comparatively good for beavers in the State and the Northeast. The NYS DEC (and its predecessors) played a central role in reintroducing and maintaining beaver populations in the Adirondacks, the Mohawk Watershed, and elsewhere in NY State [4]. In the early 1900’s legal protection and expanded introduction efforts paved the way for rewilding the landscape - or at least partly returning beavers to the ecosystem. A 1904 NY State law protected beaver: “No person shall molest or disturb any wild beaver or the dams, houses or abiding places of same.” Passage of this law included funding to purchase wild beaver for reintroduction to the Adirondacks. Funding was again appropriated in 1906, and soon thereafter 21 beavers had been reintroduced to the Adirondacks. Four of these beavers, originally from Yellowstone National Park, were relocated to Eagle Creek, part of the Fulton Chain of Lakes in the Adirondacks [25].

Map of beaver introductions and redistribution sites modified from Bump and Cook, 1941 - the core effort of rebeavering New York. Relocations were facilitated by the Beaver Bus that was purchased by En Con in 1932, and over six years over 600 beavers were redistributed across the State (yellow squares). The Mohawk watershed is shown in orange.

These introduced beavers quickly got to work, felling trees, building dams, and creating wetlands as expected. However, their activity also created new challenges related to land use, including tree loss and flooding of local property. William Barrett, a landowner in the Adirondacks whose property saw extensive damage from the downing of poplar trees and flooding due to the beavers, filed a lawsuit against NY State, arguing that the NY was liable for damage because the State had reintroduced the animals.

In 1917, Barrett v. State of New York became a landmark legal case, addressing whether the state was responsible for damage caused by the beavers and examining the extent of its authority to enforce wildlife protection laws. Barrett initially won the case, but the decision was later reversed by the Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court, establishing a critical precedent for the role of the State in wildlife management and protection. In the reversal, Judge Andrews wrote in his 1917 decision: “In liberating these beaver the state was acting as a government. As a trustee for the people and as their representative it was doing what it thought best for the interests of the public at large.” [25] (here). Thus those early introduced beavers ultimately drove a legal decision that would help establish protection of their progeny in NY State for decades.

Poplar tree felled by beavers in Schenectady County (JI Garver, 2024).

Why beavers matter in regional watershed management. Beavers and their dams provide a well known benefit of slowing the flow for flood mitigation, evening discharge for sustained flows during drought, controlling and managing sediment, and increasing biodiversity associated with wetlands. Obviously this is in contrast to the more common approach of building dikes, dams, culverts, and other “hard” structures that has been used in the last century in our war with rivers and flooding. Let’s pause and appreciate how a number of early influential writers worked to turn the tide and advocated for large-scale beaver reintroduction efforts.

In 1913, Enos Mills wrote “In Beaver World”, which was centered on direct observations of beavers in the Rocky Mountains [26]. Mills was one of the earliest advocates for beavers and the services they provide, and this book is one of the first works based on direct observation that advocated for the importance of beavers in the landscape [27]. Mills was impressed by the impact that beavers have on watersheds, and he lists key “services” that beavers provide, including erosion control and sediment trapping, flood reduction, and stream flow equalization at both high and low water. Much of this emerges in the final chapter of the book entitled “The original conservationist.” Today we refer to this as ecosystem services. Importantly, Mills understood that the engineering that beavers do to modify the landscape results in one key ecosystem service, which is flood prevention.

In his final chapter he wrote: “A river which flows steadily throughout the year is of inestimable value to mankind. If floods sweep a river, they do damage. If low water comes, the wheels of steamers and of factories cease to move, and a dry river-channel means both damage and death. Numerous beaver colonies along the sources of countless streams that rise in the hills and the mountains would be helpful in equalizing the flow of these streams. I hope and believe that before many years every rushing care-free brook that springs from a great watershed will be steadied in a poetic pond that is made, and that will be maintained by our patient, persevering friend the beaver.” He concludes: “A live beaver is more valuable to mankind than a dead one…. if protected they would multiply and colonize stream-sources. Here they would practice conservation. Their presence would reduce river and harbor appropriations and make rivers more manageable, useful, and attractive” [26].

In 1939, naturalist Bill Hamilton, who was a professor at the NY State College of Agriculture at Cornell, wrote the book American Mammals. While only a tiny fraction of this book is dedicated to beavers, he wrote a chapter entitled “Useful mammals,” and in that chapter is a section on “Soil conservators” - an important topic in the US at the time due to erosion and soil loss during the Dust Bowl [28]. “The efforts of wild animals in checking soil erosion and conserving water have been little appreciated until recent times.” He cites two early examples from Washington State where beavers were used to control flood waters and sediment transport. The Soil Conservation Service enlisted the help of beavers on Mission Creek (west of the crest of the Cascades) to control erosion caused by overgrazing and logging that resulted in flooding and sediment accumulation in the lowlands. Another project in the Yakima Valley (east of the Cascade crest) used introduced beavers to create dams to store water to even river flows in the summer, which is especially important for agriculture and irrigation [28].

Beaversprite. One important point of early beaver advocacy in NY, and an early rebeavering effort, emerged in the upper part of the Mohawk Watershed and is wonderfully documented in the book Beaversprite [29]. In the 1930s beavers were making a comeback in the State, but they still needed help. In 1935, Dorothy Richards and her husband Al requested that beavers be relocated to their land in the southern Adirondacks. At the time the NY State Department of Environmental Conservation (now NYS DEC) was looking for suitable habitat for two beavers from Pennsylvania. This effort re-established beavers in the Middle Sprite Creek, a tributary of the East Canada Creek - along the southern margin of the Adirondacks [29]. This significant tributary flows into the main stem of the Mohawk River between Little Falls and St Johnsville.

The book Beaversprite is a story of the close relationship Dorothy Richards developed with beavers, and an appreciation of their family structure, industry, and resilience. But more broadly it is about her dedication to establishing beavers, protecting beaver habitat, and promoting education and outreach about the importance of beavers and the wetlands they provide. While her story is impressive on a personal level because her beavers routinely shared the house with her and her husband, she was aware of the challenges they faced in the regional ecosystem. Richards left Beaversprite to a trust in 1966, so it could be run as a wildlife sanctuary. In 1988, the Friends of Beaversprite boycotted the trust that was managing the sanctuary due to mismanagement. In 2019, Beaversprite was acquired and reopened by the Utica Zoo as a conservation and education center, and today it is open daily to visitors (website is here).

Richards appreciated that there was conflict between beaver activity and landowners, primarily due to flooded lands. She suggests that if we make small concessions to beavers, we may end up helping ourselves: “...since their works minimize floods and droughts that cost us billions of dollars annually, as well as quite a few human lives. It has been stated by hydrologists that if beavers were allowed to live unmolested in the headwaters of streams most disastrous floods would be prevented.” [29].

Dorothy Richards suggested that we need to consider the rights of nature, and the beneficial role that beavers play in our natural ecosystem. “Riparian rights are well established among humans. What about the beavers’ riparian rights, which if regarded would guarantee maximum benefits to man in the long run?” “They are an asset no matter where they live. Somehow we need to make room for them, and come to appreciate them as a lively integral part of wild beauty - as keepers of the streams for which role they were born.” [29].

The Beaversprite conservation education center is still having an impact in shaping perceptions of beavers and the role they may play in watershed management. The center is now run by the Utica Zoo, and several years ago they were awarded a grant from the Mohawk River Basin Program (MRPB), which is administered through the NYS DEC, to develop a comprehensive education program focussed on watershed protection and the role that beaver ponds play in ecosystem health and flood control [30].

Today, all the hard work of rebeavering the State and protecting their works has paid off, and beavers have been reintegrated into the fabric of ecosystems across the State [4]. In fact it is almost certain that there are more beavers now than anytime in the last 300 years, and their numbers are growing [33], and we now face some management challenges as they expand and reoccupy sites from before the beaver era. Thus it is time we take a hard look at how we can encourage and carefully manage these bio-engineers in their efforts to slow streamflow, trap sediment, and foster biodiversity in the Mohawk Watershed.

Further reading and notes

[01] Goldfarb, B., 2018. Eager: the surprising, secret life of beavers and why they matter. Chelsea Green Publishing.

[02] Goldfarb, B., 2024. In the Arctic, Beavers Are Climate Winners. Should We Let Them Take Over? Audubon Magazine, Sp. 2024 (here).

[03] Jordan, C.E. and Fairfax, E., 2022. Beaver: The North American freshwater climate action plan. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water, 9(4), p.e1592.

[04] Gotie, RF and Brown, MK, 2022. The American Beaver in New York (1895-2005): A Century of Wildlife Conservation, Dorrance Publishing Co., 156 p.

[05] Garver, 2024. Beavers thrive with forest recovery in the Mohawk Valley: Land-use changes foster wetland expansion and climate resilience. Notes from a Watershed. Substack.com.

[06] Bump, G, and Cook, AH, 1941. Black Gold: The story of the Beaver in New York State. New York State conservation department division of fish and game, bureau of game. Management Bulletin no. 2.

[07] Coclanis, P.A., 2011. Fur, Fortune, and Empire: The Epic History of the Fur Trade in America. By Eric Jay Dolan, New York, NY: WW Norton & Company, 2010. 442 p.

[08] Lubbers, Kelly E. and Samuels, Joshua X. 2023. Comparison of Miocene to early Pleistocene-aged Castor californicus (Rodentia: Castoridae) to extant beavers and implications for the evolution of Castor in North America. Palaeontologia Electronica, 26(3):a35.

[09] Plint, T., Longstaffe, F.J. and Zazula, G., 2019. Giant Beaver palaeoecology inferred from stable isotopes. Scientific Reports, 9(1), p.7179.

[10] Feranec, R.S. and Kozlowski, A.L., 2010. AMS radiocarbon dates from Pleistocene and Holocene mammals housed in the New York State museum, Albany, New York, USA. Radiocarbon, 52(1), pp.205-208.

[11] Hall J, and Wyman J. 1846. Notice on the geological position of the cranium of the Castoroides ohioensis. Boston Journ. Nat. Hist 5, 385–401 (here).

[12] Hartnagel CA, Bishop SC. 1921 The mastodons, mammoths and other Pleistocene mammals of New York State: being a descriptive record of all known occurrences. Albany, NY: University of the State of New York. (Here p. 83)

[13] Hall, J. 1868. Notes and observations of the Cohoes Mastodon. 21st annual report, State Cabinet Natural History for 1867, p.99-128.

[14] Miller, N.G. and Griggs, C.B., 2012. Tree macrofossils of Younger Dryas age from Cohoes, New York State, USA. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 49(5), pp.671-680.

[15] Toney, J.L., Rodbell, D.T. and Miller, N.G., 2003. Sedimentologic and palynologic records of the last deglaciation and Holocene from Ballston Lake, New York. Quaternary Research, 60(2), pp.189-199.

[16] Mahaney, W.C., 2023. The Younger Dryas Boundary (YDB): terrestrial, cosmic, or both? International Journal of Earth Sciences, 112(3), pp.791-804.

[17] Miller, N.G. 2008. The Cohoes mastodon and Younger Dryas in eastern New York. Pp. 19–25. In Glacial Geology of the Northern Hudson Through Southern Champlain Lowlands. Edited by D.J. De Simone, G.R. Wall, N.G. Miller, J.A. Rayburn, and A.L. Kozlowski. Guidebook to Field Trips for the 71st Annual Reunion Northeastern Friends of the Pleistocene. 58 pp.

[18] Ruedemann, R. and Schoonmaker, W.J., 1938. Beaver-dams as geologic agents. Science, 88(2292), pp.523-525.

[19] Vernon, H., 1978. The Dutch, the Indians, and the Fur Trade in the Hudson Valley, 1609-1664. Neighbors and Intruders: An Ethnohistorical Exploration of the Indians of Hudson's River, (39), p.197.

[20] Venema, J., 2003, Beverwijck: a Dutch village on the American Frontier, 1652-1664. Verloren/Hilversum, The Netherlands, State University of New York Press, Albany NY. 528 p.

[21] Hays, W.J., 1871. Notes on the range of some of the animals in America at the time of the arrival of the white men. The American Naturalist, 5(7), pp.387-392.

[22] Burke Jr, T.E., 2009. Mohawk Frontier: The Dutch Community of Schenectady, New York, 1661-1710. State University of New York Press.

[23] Naiman, R.J., Johnston, C.A. and Kelley, J.C., 1988. Alteration of North American streams by beaver. BioScience, 38(11), pp.753-762.

[24] Varekamp, J.C., 2006. The historic fur trade and climate change. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 87(52), pp.593-597.

[25] Andrews, 1917. Barrett v. State of New York, 116 N.E. 99 (NY1917), New York Court of Appeals. 116 N.E. 99, 220 NY 423, 1917 N.Y. Lexis 987 (reversal decision is here at the Court Listener).

[26] Mills, Enos A., 1913. In Beaver World. Houghton Mifflin Co, Riverside Press , Cambridge (available through the Gutenberg project here).

[27] Philip, L., 2022. Beaverland: How One Weird Rodent Made America. Twelve publishers, NY and Boston, 317 p.

[28] Hamilton, W.J., Jr. 1939. American Mammals: Their lives, habits, and economic relations. McGraw Hill, NY and London. 426 p. (here)

[29] Richards, D. and Buyukmihci, H.S., 1977. Beaversprite: my years building an animal sanctuary. Chronicle Books, San Francisco. 191 p.

[30] Beaversprite funding by NYS DEC in 2019: Utica Zoological Society: Beavers, Wetlands and Watershed Protection “This project will design and implement a comprehensive water education program focusing on watershed protection and the role beaver ponds and wetlands play in flood control and creating healthy ecosystems. Programs will take place at the Utica Zoo's Conservation Education Center, Beaversprite, in Oppenheim in Fulton County, and include family programs, arts integration camp, and resources and tools for local teachers.”

[31] Hey, D.L. and Philippi, N.S., 1995. Flood reduction through wetland restoration: the Upper Mississippi River Basin as a case history. Restoration Ecology, 3(1), pp.4-17.

[32] Richter, DK., 1992. The Ordeal of the Longhouse: The Peoples of the Iroquois League in the era of European Colonization. University of North Carolina Press, 436 p.

[33] Garver, JI. 2025. Leave it to beavers: the expanding role of Nature’s engineers in the Mohawk Watershed. In Rodak, CM, Garver, JI, and Smith, JA (eds), Abstracts and Program, Mohawk Watershed Symposium, v. 15, p. 23-26.

Excellent piece.