Invasive Water Chestnut is choking the lower Mohawk

Explosive growth driven by sediment blocked by the Crescent dam

Invasive Water Chestnut (Trapa natans) is a shallow-water invasive aquatic plant that has colonized vast stretches in the lower Mohawk River in a spectacular way. Growth has been dramatic in the last decade and the primary driver for the ecosystem may be rapid sediment accumulation behind the Crescent dam owned by the NY Power Authority (NYPA). An increase in storm magnitude and dramatic flooding in the headwaters in the last few decades - especially the Schoharie Creek that drains northward from the Catskills - has changed the ecosystem dramatically due to sediment accumulation behind the Crescent dam. This sediment is manifested in infilling that has resulted in shallows and island growth - perfect habitat for Water Chestnut. Explosive growth in the last decade is choking marinas and impairing boating.

The Crescent dam and Vischer Ferry dam are the last major obstacles to sediment transport in the Mohawk River, and because they are permanent dams, coarse sediment is trapped and unable to get flushed downstream to the Hudson. Upriver, at least to the confluence with the Schoharie Creek, all the other dams are removable and retracted in the winter (non-navigation season), so sediment is able to move down river. We need a sediment management plan to address the enormous volume of material that is being flushed down river and getting trapped behind the Crescent Dam. We also need a regional solution to invasive species, and this is an enormous challenge. But if we don’t make some hard choices now, other invasive aquatic plants - such as Hydrilla, which can grow in deeper waters - may enter the system and impair boating and marina operations further.

The Crescent hydroelectric power facility, owned by the NY Power Authority or NYPA, is currently up for review by the Federal Energy Regulatory Agency (FERC), and the re-liscensing process considers the environmental consequences of power generation. Hopefully this impairment to boating and the economic consequences are considered in the review process because if we wait another few decades to address this problem, only a meandering channel in thick sediment deposits will remain.

Water Chestnut and allied aquatic plants clog boat passage in the Albany Marine Services Marina on the lower Mohawk. Most marinas in the lower Mohawk spend considerable time and resources clearing this invasive plant for boat passage (Photo: JI Garver, September 2023).

Water Chestnut. The lower Mohawk is ground zero for this invasive aquatic plant, partly because it was introduced into Collins Pond in Scotia over a century ago. It has been problematic for some time. In 2005, the NY Invasive task force told us: “Water Chestnut was first discovered in Collins Pond in Schenectady County - it still chokes many of our lakes, ponds and slow-moving rivers.” and the growth of this plant and its allies “choke many of our waters, impeding boating and swimming and crowding out our native species.” [1]. An early effort to mitigate infestation of aquatic plants was initiated on Collins Pond in the late 1970s when coordinated dredging was done to remove organic-rich sediments and disrupt the habitat from both the Curly-leaf Pondweed and Water Chestnut [3]. The nutrient-rich sediments were thought to contribute a significant amount of phosphorus to the lake.

In NY State much of the work on identifying and mitigating invasive species is done by the Partnership for Regional Invasive Species Management (PRISM), and the State is divided into eight regional districts. Hanna Coppola is the Aquatic Species program manager at the Capital District PRISM, and she directly addressed the problem of the Water Chestnut on the lower Mohawk at the Mohawk Watershed Symposium in March 2023. She noted that “Trapa natans (water chestnut) is a growing issue concerning both ecologic and economic values of the Mohawk River. …[It] reduces habitat and impacts recreation, transportation and property values. The expansive volume of T. natans in the Mohawk River requires a partnered response with strategic management. Current monitoring surveys have delineated approximately 850 acres of T. natans. Identifying highly affected ecologic and economic areas will assist in the creation of management plans.” [4]

The Town of Colonie reclaims its boat ramp. The Town of Colonie has waterfront and a boat ramp in the Mohawk River Park, but access has been lost due to sedimentation and growth of a thick mat of Water Chestnut. In 2022, the newly elected town supervisor, Peter Crummey, was determined to restore access to the River [5]. In the summer of 2023, the Town applied for and received a $48k grant from the Mohawk River Basin Program (here) to remove the invasive plant so that boats could access the River [2]. In August 2023 the Town successfully removed Water Chestnut in front of the ramp area - about 65 tons - using mechanical harvesters and volunteer pullers (in the shallow water) and thus they opened access for boaters [6,7]. To do this in 2023, they used about ⅓ of their grant of $48,000, which is aimed at waterfront revitalization. Once the Water Chestnut was removed, the town supervisor acknowledged that the next step was removal of the sediment because the ramp area had shallowed due to sediment accumulation.

While the Town of Colonie clearing project is impressive - as was the press event associated with it - marina operators on the lower Mohawk have been clearing Water Chestnut on a much larger scale for years just to stay in business. For example, Albany Marine Services Marina, just downriver, routinely clears 10-15 acres annually with purposefully-built harvesters. For all marinas on this part of the Mohawk, clearing Water Chestnut (and sediment removal), ensures survival, but obviously it is a major annual expense, and headache. With this in mind, let’s look at the bigger picture in the Crescent pool and how this problem has evolved.

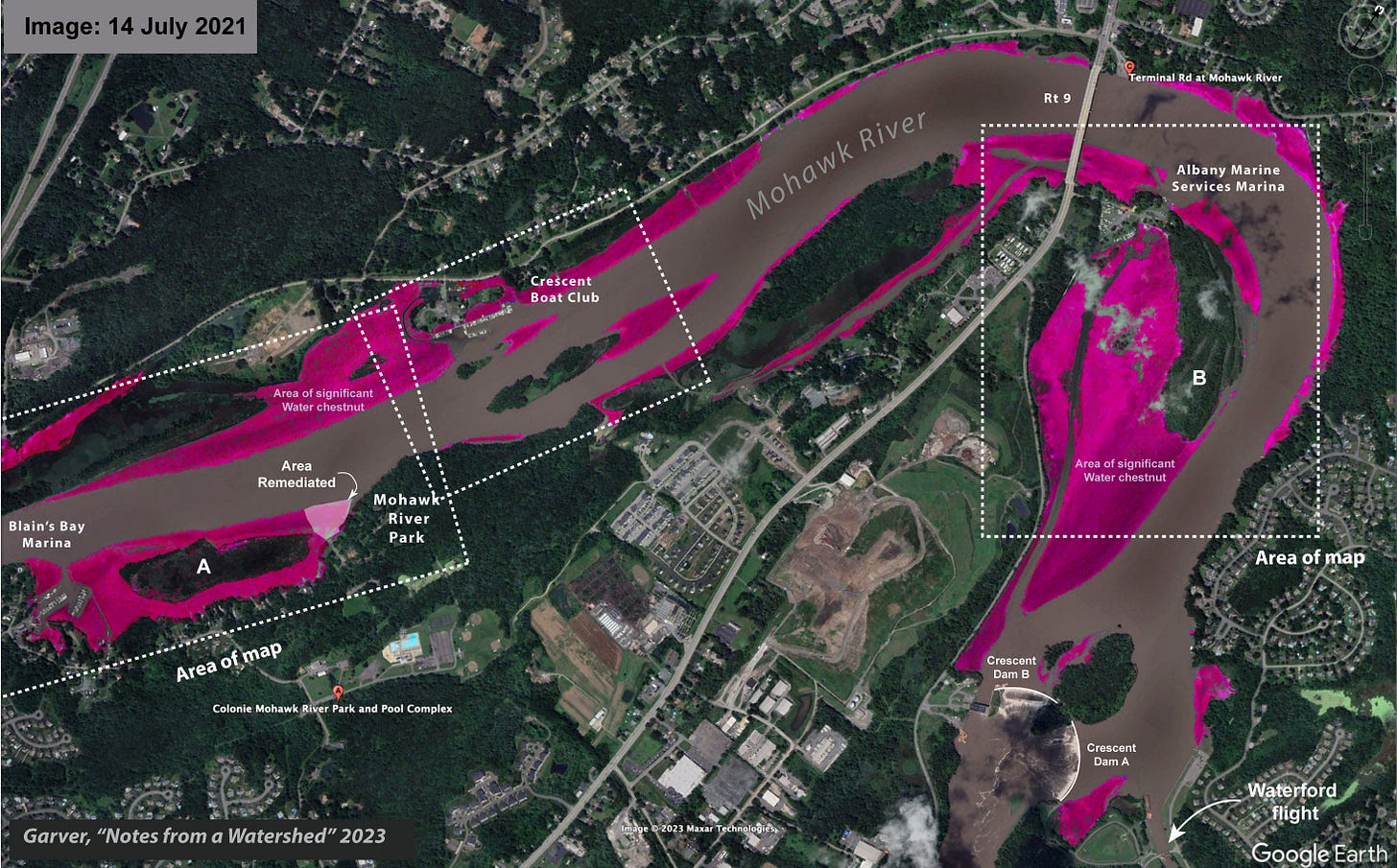

Lower Mohawk problem. Water Chestnut infestation in the lower Mohawk is extensive, and it is easily imaged using satellite images taken in the summer (on Google Earth). The map below is only part of the Crescent pool, and the areas on the river that have the correct spectral color for Water Chestnut are shown in shades of magenta. Superimposed on this map are the two areas of detailed analysis where island growth and sediment accumulation have been significant (A and B).

Mapping of the extent of Water Chestnut above the Crescent dam on the lower Mohawk River. Areas with significant Water Chestnut are shown in magenta. Water Chestnut thrives in shallow water (<10 ft), so this map essentially also shows where the River is shallow and where sediment is accumulating. The site of remediation by the Town of Colonie is adjacent to Mohawk River Park. The timeline of the growth of A and B (on map) are shown in the graph below. Google Earth satellite image from July 2021.

The Crescent pool (between Erie Canal lock E6 and E7) is flat, wide, and held up by the Crescent dam, which is actually made up of two dams (one 52’ high, one 32’ high) that were constructed in 1908 [8]. Thus this dam has been in place and has collected sediment for 115 years, but satellite images show that sediment has significantly filled channel fringes more rapidly in the last 10-15 years. Given the infilling of shallow waters and side channels, it is clear that infilling has been especially dramatic and profound since Hurricane Irene (2011) - the biggest and most significant event in the Catskill-draining part of the watershed since the dam was constructed.

Animation showing eighteen years of sediment build up and growth of Water Chestnut that has profoundly affected the Mohawk River and working marinas. Shown here is the Crescent Boat Club and the main channel of the Mohawk fading between 29 June 2001 and 14 July 2021 (using Google Earth images). Note that the marina has moved docks outward, and has lost the use of one of the interior spaces for boat slips. Sediment buildup has produced shallows, now colonized by Water Chestnut, in the lee of the mid-channel islands. Private docks are abandoned or require cutting paths through the Water Chestnut.

The explosive growth of this noxious aquatic plant in the lower part of the Mohawk River may be due to sediment infilling and expansion of its preferred shallow-water ecological niche. It is possible that much of the sediment originated from the Schoharie Creek, which has seen the magnitude of the 100-year flood almost double in the last four decades. Hurricane Irene was a 500-yr event in the Schoharie [17] and tremendous volumes of sediment were washed into the Mohawk.

Sediment from tributaries includes both suspended load (fine silt and mud), and bedload (sand and gravel). After Irene, a plume of suspended sediment was seen in satellite images of the lower Hudson River in NY City (see here). But the fate of the bedload is harder to track. It is almost certain that most of this sediment has bypassed the removable dams, which are lifted out of the water in the winter, and collected in the two lower pools on the Mohawk that are supported by permanent dams - the Vischer Ferry dam (at E7) and the Crescent dam (at E6). Because the Crescent pool is wider and flow is slower, it is nearly certain that the largest fraction of that sediment is trapped primarily behind the Crescent dam (between locks E6 and E7 or the Crescent pool).

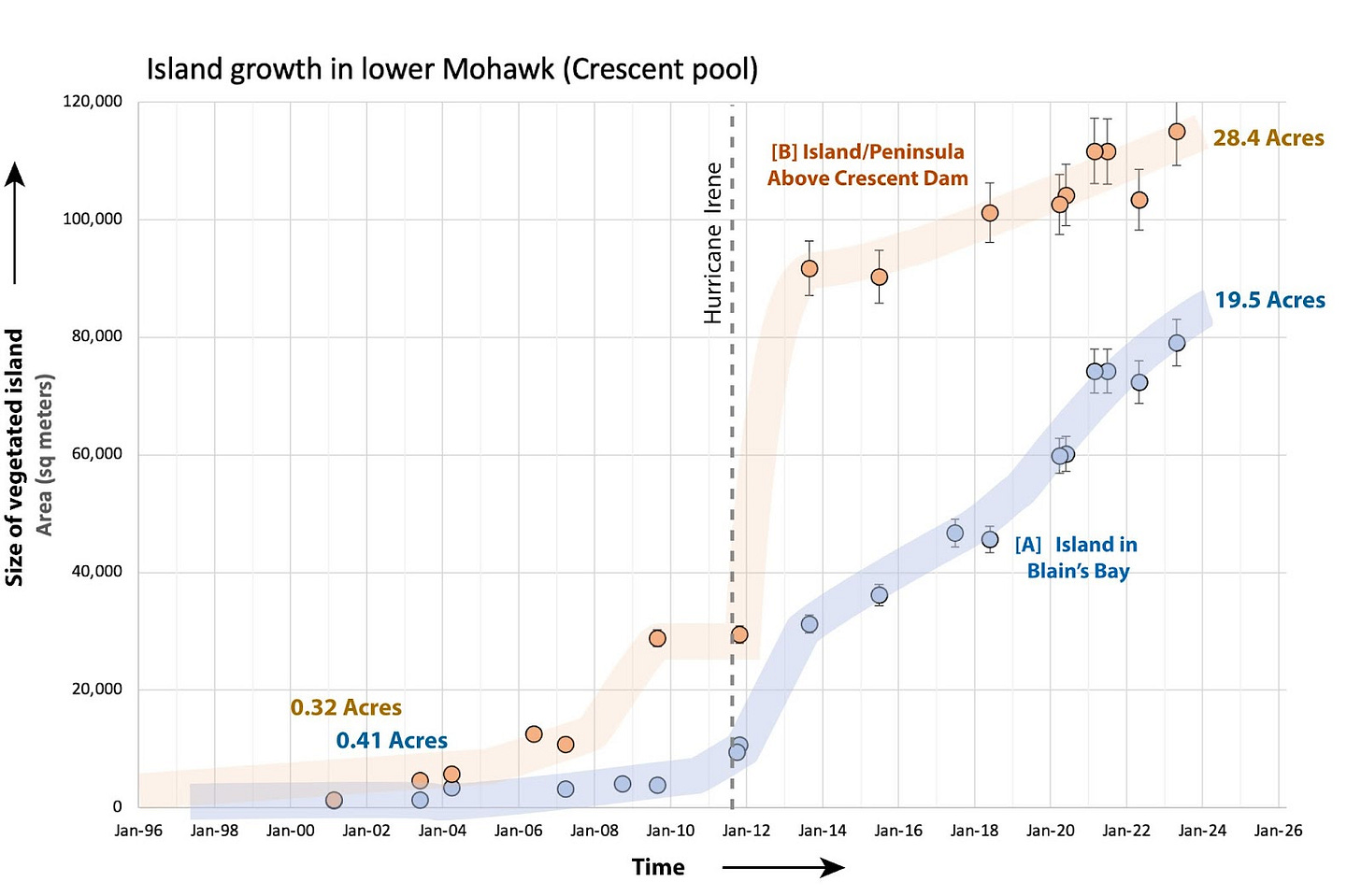

Sediment infilling indicated by island growth. Measuring sediment accumulation behind a dam in a river setting requires collection of river profile data over time so comparisons can be made concerning infilling and depth reduction. These data are difficult and expensive to obtain, and I don’t have them. One simple way to approach this problem is to measure the accumulation of sediment that builds up above the normal river level, and this can be done with satellite images that record changes in the landscape over time. For this area, Google Earth has high-resolution images going back to 2001. Using those images I mapped the change in island geometry, and then calculated the change in the size of islands that were exposed and able to support non-aquatic vegetation. The plot below shows the result from two of those islands. The rate of growth was most significant following the 2011 floods of Irene (and Lee), but note the pace of extreme rainfall events in the region has quickened [14, 18], so the sediment problem is just going to get worse with time.

This time series above shows the growth of vegetated islands due to sediment accumulation in the lower Mohawk River in the area of the Mohawk River Park (Colonie), Blain’s Bay, Klam’r, and Diamond Reef marinas (base photo 2001). The rate of island growth in terms of exposed vegetated area is plotted in the graph below (blue).

This time series above shows the growth of vegetated islands due to sediment accumulation in the lower Mohawk River in the area just above the Crescent dam (base photo 2001). The rate of island growth in terms of exposed vegetated area is plotted in the graph below (orange). Growth has been significant in the years following Hurricane Irene (2011).

Plot of the vegetated area of two islands in the lower Mohawk above the Crescent dam (see “A” and “B” on map above). The larger island is now a 28-acre peninsula that has impaired operations at the Albany Marina Services Marina. Sediment accumulation behind the Crescent dam increased following Hurricane Irene, which liberated substantial volumes of sediment, especially in the Schoharie Creek.

Marinas, boats, and recreation. Along this stretch of the River there has been a major economic impact to marinas. There has been loss of members and slip space, loss due to the inaccessibility of the marina to through-going traffic, loss due to time and resources to keep channels open, and loss due to a significant reduction in fishing activity - including tournaments. We need healthy waterfronts and the economic and recreational activity that comes with boating, fishing, paddling, and other recreational activities on the Mohawk. If sediment continues to build behind the dam, and Water Chestnut continues to choke the shallows, we will lose this precious resource.

Relicensing of the NYPA’s Crescent Hydroelectric Project (at the Crescent dam) requires, among other things, an evaluation of recreational activity and accessibility in the project area. The FERC relicensing process requires a evaluation as to whether the operation of hydroelectric schemes have an environmental impact and how they may impact recreational opportunities. For FERC relicensing, a recreational study on the Crescent pool was conducted in 2021 (here, see their appendix D) [8]. In the study, access points were evaluated including the Town of Colonie’s Mohawk Park: “The site provides picnicking opportunities and cartop and trailered boat launching access to the Crescent impoundment.” At the time, this was, basically, incorrect. Photos included in the report (esp. photos 46,47, and 48, p. A29-29 in Appendix D) clearly shows that this ramp was inaccessible and clogged with water chestnut, something that has been a clear concern for those that work at the Park (Appendix D, p. 25) [8]. This impairment is why the Town of Colonie later applied for a Waterfront revitalization grant from the Mohawk River Basin Program to remove the clogging water chestnut so it can used by light watercraft.

For both the Crescent Boat Club and the Blain’s Bay Marina the NYPA recreational report notes that “Water chestnut was observed at the marina during the onsite inventory. The site operator reported that the water chestnut must be mechanically removed on a continuous basis to maintain access to the boat slips'' (p. A-28) [8]. But nowhere is there a mention of the significance of the buildup and sediment and impairment to boating caused by shallowing conditions. It seems clear that the Crescent Power project and associated dam are having major impacts on the recreational opportunities in the Crescent pool, and this impact is not captured in the Updated Study Report of 2022 that accompanied the relicensing application to FERC [8]. Thus it is not difficutl to conclude that buildup of sediment behind the dam, and the growth of Water Chestnut, are collectively harming recreational activity - especially fishing and boating - above the Crescent project.

Proactive approach to invasive species. Nearly twenty years ago in 2005, the NYS DEC and the Department of Agriculture released a final report from the Invasive Species Task Force entitled: “Addressing invasive species requires: Prevention, Early Detection, Rapid Response & Eradication, Control & Management, and Restoration” [1] The 2005 Invasive Species Task Force report concluded that: “The members of the New York State Invasive Species Task Force appear to be more reactionary than proactive with regard to the invasive species problem, with a growing but still inadequate degree of inter-agency and public-private coordination and cooperation.” (p. xi) [1].

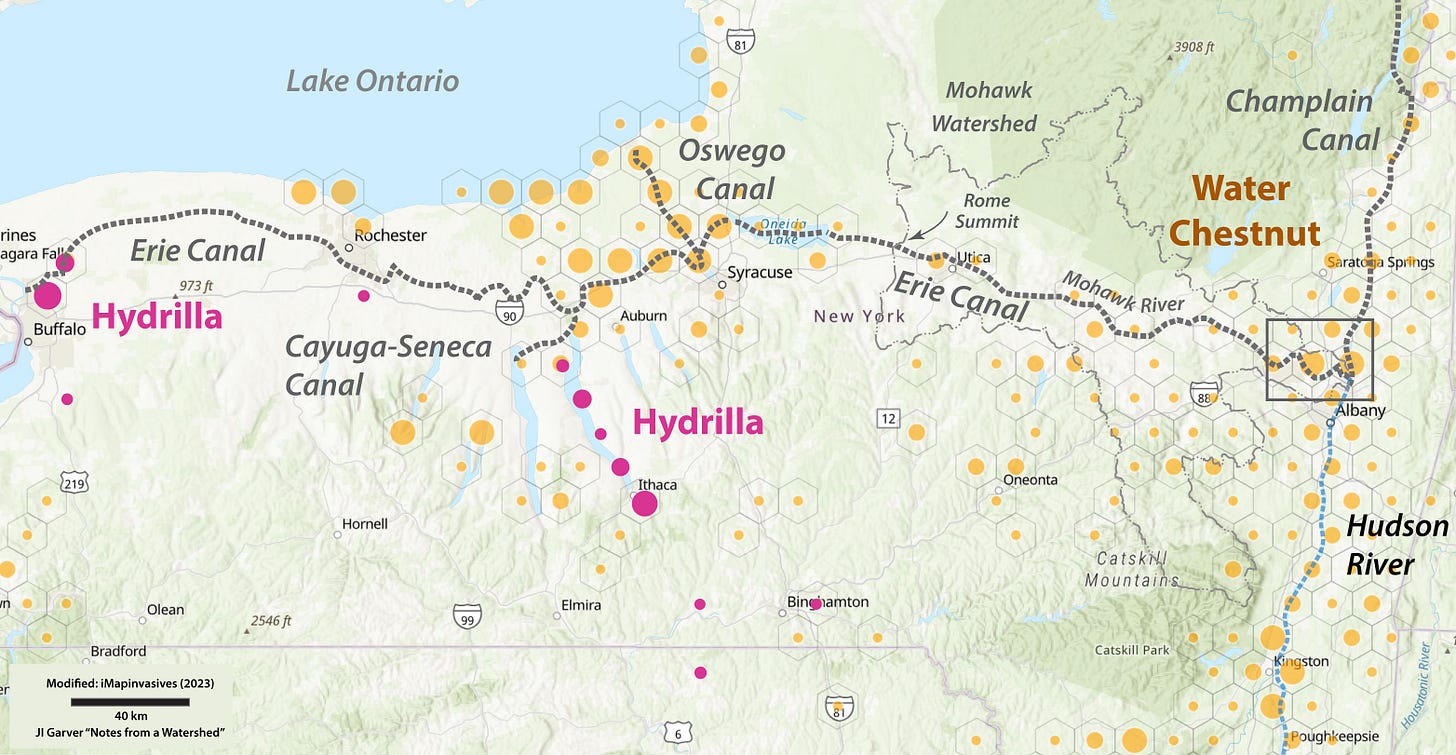

Proactive invasive species management is difficult. It requires using science to address a known threat that may have uncertainties associated with the timeline of invasion, economic impact, and ecosystem impairment. Nonetheless, everyone involved with invasive species mitigation emphasizes that prevention is the most effective strategy. A well known pathway for aquatic invasive species is the Erie Canal, and there has long been the recognition that we need a multi-taxa or all-taxa approach to prevent the spread of invasive species along this corridor. This sort of proactive approach is complicated because the Erie Canal is one of the most iconic and historic waterways in the country, and the challenge is to implement effective proactive measures but also keep boats moving through the corridor.

There are a number of disrupting aquatic invasive species on the horizon that may also have very high environmental impacts. The fast-growing Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata), which thrives in even deeper water than Water Chestnut, is in the Canal System, and if it spreads to the lower Mohawk it will be a disaster. According to NY invasive species info: “Hydrilla can invade deep, dark waters where most native plants cannot grow. The plant’s aggressive growth (hydrilla’s 20 – 30 foot stems can add up to an inch per day) can spread into shallow water areas and form thick mats that block sunlight to native plants below, effectively displacing the native vegetation of a waterbody.” They also note that: “The risk of the plant spreading to the rest of Cayuga Lake and other regional waterbodies in the Finger Lakes region is considered to be substantial” [9].

For the Capital District PRISM (which includes the lower Mohawk), Hydrilla is a Tier 1A invasive species that has the highest level of early detection survey efforts because it is in adjacent areas and its ecological impact is very high [11]. Note that most of the River and Canal in the lower Mohawk River is less than 20 ft deep, which means even the main channel may be compromised if this aggressive aquatic plant gets established. So this is serious if you are a boater or you care about keeping the Erie canal open.

The distribution of both Water Chestnut and Hydrilla in NY State as displayed in iMapinvasives in 2023. Hydrilla is in the Canal system, and we need to do everything possible to keep it from spreading elsewhere in this connected waterway - including the Mohawk Watershed. Map modified from [10]

Solutions. The Water Chestnut problem in the lower Mohawk River is acute. Outlined in this Note is an invasive species problem that has been facilitated by sediment accumulation that is driven by bigger storms, more summer/fall precipitation, and sediment transport [15, 17]. Three solutions need to be considered. First, we need to support efforts to mitigate Water Chestnut by mechanical harvesting on a large scale. Second, we need to address sediment accumulation in the lower Mohawk. Third, we need to proactively contain other looming AIS threats that are using the Canal to hitchhike and spread along the corridor [12,13].

For the immediate problem in the Crescent pool, NYPA/Canals needs to outline and adopt a sediment management plan, and ideally this should be part of the FERC relicensing for the Vischer and Crescent projects. The re-licensing, which would be for 40 years, is currently underway. We can't wait that long for a solution: the process needs to start now.

Sediment infilling is being driven by an increase in extreme precipitation events, which are dominated by flashy summer storms that are mobilizing sediment in the channel, banks, and floodplains upstream - especially in the Schoharie Creek that drains the Catskill Mountains [14,15, see also 17]. Much of this sediment is being trapped behind these permanent dams on the lower Mohawk. We need proactive strategies to address invasive species - because more are on the horizon - and we also need NYPA and Canals to formulate a sediment management plan.

This problem is not going to fix itself, and it is certain that it will worsen with time. Without direct intervention sediment accumulation combined with choking invasive plants may make this part of the Canal impassable in the near future.

This and other Notes from a Watershed are available at: Mohawk.substack.com

Further reading

[1] 2005, NY Invasive Species Task Force. Final report of the New York State invasive species task force (NYS DEC and NYS Dept Agriculture) (Here)

[2] 2023, August 31. NYS DEC Press press release. Lieutenant Governor Antonio Delgado and DEC Announced $600,000 in Mohawk River Watershed Grant Awards Funds Will Help 14 Projects Conserve, Preserve, and Restore Mohawk River Watershed. Part: “Town of Colonie, Colonie Mohawk River Park Waterfront Access Revitalization Project, $47,674.03: A project to mitigate water chestnuts within four to six acres of the park and river shoreline using a professional contractor and community volunteers. This will include maintenance dredging to install a new boat launch at the park, restoring public access to the Mohawk River.” Here:

[3] George, C.J., Tobiessen, P.L., Snow, D. and Jewell, T.K., 1982. The Monitoring of the restorational dredging of Collins Lake. US Environmental Protection Agency, Scotia, NY. EPA-600/S3-81-017. (here)

[4] Coppola, H., 2023. Mitigation approaches to water chestnut (Trapa natans) on the Mohawk River. In: Garver, J.I., Smith, J.A., and Rodak, C. 2023. Proceedings of the 2023 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March 17, 2023, Volume 13, 82 pages.

[5] 2022, Franco, Jim (July 13), The Weeds are winning: Water Chestnuts in Colonie. Spotlight news (Here)

[6] 2023, Hughes, Steve (1 Sept). Colonie clears town park of water chestnuts for kayaking: The town removed invasive water chestnuts from the Mohawk River Park waterfront. Albany Times Union.

[7] 2023, NYS DEC Twitter announcement on the Mohawk River Basin Program grants, and the successful remediation of the boat ramp in the Town of Colonie (Here).

[8] 2021 NYPA relicensing for Crescent and Vischer Ferry projects. “Updated Study Report” Feb 2012 (Here).

[9] 2023, New York Invasive Species (IS) information - New York State's gateway to science-based invasive species information (website here), Hydrilla in NY State (Here).

[10] 2023, iMapinvasives. Sharing information for strategic management. Website (Here).

[11] The Capital District Partnership for Regional Invasive Species Management or PRISM is Here. The list of aquatic invasive species is Here, and the Invasive species tiers in each PRISM are Here. In the Capital District, Hydrilla is a Tier 1A species with a very high potential impact, and thus it is one of the top priorities because it has yet to reach this PRISM area. Water Chestnut is a Tier 4 species in the Capital District - and every other PRISM in NY State - because eradication from the area is “not feasible” and the focus is on local management.

[12] Garver, J.I., 2022, Aquatic pathway between the Mohawk and Lake Champlain: Aquatic invaders are using the Erie Canal to get into Lake Champlain. Notes from a watershed, Substack.com (Here)

[13] Garver, J.I., 2021, Stop the invasion: barriers needed between the Mohawk and the Great Lakes: Recent capture of the Round goby in the Hudson River highlights the need to address invasive species in the Erie Canal Corridor. Notes from a watershed, Substack.com (Here).

[14] Garver, J.I., 2021, Extreme Rainfall in the Northeast: It's raining a lot and our wastewater system is bursting at the seams. The resulting sewage overflows are impairing our waterways. Notes from a watershed, Substack.com (Here)

[15] Cockburn, J.M. and Garver, J.I., 2015. Abrupt change in runoff on the north slope of the Catskill Mountains, NY, USA: above average discharge in the last two decades. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 3, pp.199-210. (here)

[16] Gazoorian, C. 2012. How extreme was Irene? A Comparison of the 2011, 1996, 1987 flood events along the Schoharie Creek. In: Cockburn, J.M.H. and Garver, J.I. (eds) Proceedings of the 2012 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March 16, 2012. P.17-22.

[17] Burns, D.A., Klaus, J. and McHale, M.R., 2007. Recent climate trends and implications for water resources in the Catskill Mountain region, New York, USA. Journal of Hydrology, 336 (1-2), pp.155-170.

[18] Plummer, I, and Garver, JI. 2023. Changes in temperature and precipitation patterns in the Mohawk Watershed: implications for flooding, water quality, and ecosystem health. In Garver, J.I., Smith, J.A., and Rodak, C. 2023. Proceedings of the 2023 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March 17, 2023, Volume 13, p. 54-58.