Aquatic pathway between the Mohawk and Lake Champlain

Aquatic invaders are using the Erie Canal to get into Lake Champlain

We are at a critical juncture for addressing aquatic invasive species (AIS) in NYS canals that connect our waterways. In 2019 a study commissioned by the Reimagine the Canals task force recommended watershed separation to address the range expansion of invasive species that have been using the Erie Canal to cross between the Mohawk-Hudson on the Atlantic Slope and watersheds of the Great Lakes. In 2022 the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) completed a study addressing options to stem the flow of aquatic invaders into Lake Champlain through the Champlain Canal from the Hudson River. While these studies were being written, the Round goby, a benthic invader from eastern Europe accidentally introduced to the Great Lakes through freighter ballast water, was steadily advancing along the Erie Canal through the Mohawk and into the Hudson River, and it now threatens Lake Champlain. The arrival of this fish in the Hudson in 2021, after traversing the Mohawk, highlighted the urgency of containment, and thus the importance of these two recent studies aimed at combating invasive species in the canals. These two important efforts are interrelated: an effective barrier at the summit of the Erie Canal (at Rome NY), would be a critical piece of the puzzle for keeping AIS out of Lake Champlain. The two efforts should be coordinated in a broader effort at securing our waterways and protecting our aquatic ecosystems.

Erie Canal. The Erie Canal connects the Hudson River with Lake Erie, and when it was built it was the first navigable connection between the Atlantic (through the Hudson) and the Great Lakes. The eastern section lies mostly within the Mohawk River, and it leaves the Mohawk and crosses the drainage divide just west of Rome. Stopping AIS in the Erie Canal was part of the focus on the Reimagine the Canals task force in 2019 [01]. This task force, appointed by Governor Cuomo, was exclusively focussed on the Erie Canal, with the mandate to reimagine the next 50 years of the Canal it transitions from a transportation corridor largely for commerce to a recreational corridor that is more sensitive to aquatic ecosystems and the needs of local communities. The task force commissioned studies to evaluate flooding, ice jams, wetlands, invasive species, and other issues central to the mandate.

The invasive species report was focused on best options to stop or stem the flow of invasive species along the Erie Canal corridor (ECC) sometimes referred to as the “invasive superhighway” [02]. In the report, which was completed by R2 Resource Consultants, an “All AIS species” approach was taken. This approach means mitigation solutions are required for both “unassisted dispersers,” such as White perch, Asian carp, Round goby, and sea lamprey, and “hitchhikers” that cling or attach to boats, such as zebra mussels, and a number of aquatic plants.

The R2 study of the Erie Canal study cast the problem in clear and stark terms: 1) The NYS Canal system poses a risk of spread of invasive species to the majority of inland water bodies in NYS; and 2) the Great Lakes watershed and the Mohawk-Hudson watershed need to be separated from adjacent basins. The study focused on proposed barriers along the ECC at three primary sites for intervention: Tonawanda (near the Lake Erie entrance), Oswego (near the Lake Ontario entrance), and Rome (at the summit between the Great Lakes and the Mohawk-Hudson). In the final report, written in 2019, the consultants recommended the Watershed Divide alternative that aims to prevent spread of AIS from the Great Lakes. The Task Force took all of the information gathered and made a number of recommendations to the Governor in December 2019, and in January 2020 he announced initial funding that primarily targeted flooding.

In the recommendation to the Governor, the Task Force report did not make a specific recommendation for an AIS intervention strategy. The report stated that the Canal Corp should work with the NYS DEC to “further study mechanisms for retrofitting canal infrastructure to establish AIS cordon points with potential locations in Rome, Rochester, and Oswego.” Since that time no new studies have emerged, and thus one could conclude that this further evaluation didn’t happen. It needs to. Meanwhile, progress was being made on the barrier study on the Champlain Canal.

Champlain Canal. The Champlain Canal connects the Hudson River with Lake Champlain. Completed in 1823 - two years before the Erie Canal - the 60-mile-long Champlain Canal is a series of 11 locks that provide a connection between the Mohawk-Hudson to the south and Lake Champlain to the north. The canal goes up and over the drainage divide that has long separated these two distinct watersheds. In the series of eleven locks, locks C8 and C9 straddle the drainage divide, and hence efforts at mitigating aquatic invasive species are focussed on the “summit” between the two watersheds.

The Lake Champlain Committee (LCC) notes that more than 60% of the exotic species with a known pathway entered the Lake through canals, with the primary pathway being the Champlain Canal. The pressure is from the south, the Hudson River in particular. According to the LCC, the Hudson has over twice as many exotic species as Lake Champlain; the Great Lakes host nearly four times more [03]. According to the Lake Champlain Committee, invasions in the last two decades include Alewives, Fishhook waterfleas, Spiny waterfleas, and Eurasian watermilfoil [03].

For well over a decade efforts have been focussed on stemming the flow of aquatic invaders in the Lake. After authorization in Congress as part of the 2007 Water Resources Development act, the letter from the Canal Corp to the USACE requesting the AIS study was written in 2009. In this letter, Carmella Mantello, then director of the NY State Canal Corporation, noted that the first Canal aquatic invasive species stakeholder meeting was held in November 2008 [05]. In 2010, Mary Thill from Saranac Lake wrote an opinion piece in the Adirondack Explorer where she advocated for an aquatic barrier on the Champlain Canal because she saw threats of invasive species to the Lake Champlain ecosystem. She worried about aquatic invasives displacing and altering the Lake Champlain ecosystem, and in fact was concerned by displacement that may eventually be caused by the “aggressive Round goby” [06].

In 2015, the Lake Champlain Committee noted that further delays in planning for an invasive barrier were caused by the shift in key personnel at the NY Canal Corporation [07]. Then in 2016 the Lake Champlain Committee published a damning piece that faulted a bureaucratic web of finger-pointing, largely between the USACE and the Canal Corporation, and associated legal issues that stalled progress on studying and implementing options [08].

Regardless of the timeline, the need was clearly pressing. Lori Fisher of the LCC noted in 2016 that "The barrier is a key tool in protecting Lake Champlain from additional invasive species. Of the exotic species whose origin to the lake is known, over 60 percent entered via canals, particularly the Champlain Canal. Zebra mussels, Eurasian watermilfoil, water chestnut and white perch all came through the Champlain Canal and many more species are poised to join them" [07].

Invasive species barrier study Phase I report for the Champlain Canal. In 2022, the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), released its long-awaited report, which was entitled “Champlain Canal Aquatic invasive species barrier study Phase I report” [04]. A statement in the beginning of the report clearly identifies the source and pathway of the threat to the Lake: “Aquatic nonnative species (ANS) and invasive species in the Hudson River pose a threat to Lake Champlain. A dispersal barrier in the Champlain Canal, which connects the Hudson River to Lake Champlain, could prevent multi-taxa biological traffic including fish, plants, plankton, invertebrates, and pathogens, from reaching the lake.” It continues: “Aquatic invasive species (AIS) present in the surrounding Great Lakes, Erie Canal, and Hudson River (e.g., hydrilla, round goby, Asian clam, quagga mussel, Asian carp, and snakehead) are a threat to Lake Champlain because of their potential movement from the Hudson River or the Great Lakes through the Erie Canal to Lake Champlain and the economic and ecological impacts they may cause.”

The subtle and direct economic impact of invasive species can be quantified, and quantification helps put the cost of treatment in perspective. In 2005 David Pimentel at Cornell University published a paper in Environmental Management where he estimated the economic losses due to biologic invaders in the Mohawk-Hudson watershed was approximately $500 million per year ($759 million inflation-adjusted for 2022): 80% of these estimated losses were in commercial and sport fishing, largely in lost opportunities [09]. According to Pimentel the solution is straightforward: “Prevention is the only practical means of dealing with the alien invasive species problem in the New York State Canal and Hudson River and the Great Lakes Basin ecosystems, because exterminating an exotic species once it is established is nearly impossible.” To address the invasive threat he suggests spending 10% of the annual damages on prevention strategies, which, in this case, would be ~$50 million per year (~$76 million inflation-adjusted assuming damage now is the same as in 2005).

The 2022 USACE Champlain Initial study considered ten treatment control measures and then evaluated these in a set of six alternative plans. The evaluation considered the context of effectiveness, cost, and adherence to original guiding parameters, which included continuation of boat traffic. With an overall goal of reducing or eliminating AIS, a few key stakeholder-determined constraints guided the process. These constraints required the final plan to: “1) Maintain a viable navigable connection for commercial and recreational vessel traffic between Lake Champlain and the Hudson River; 2) Maintain the Champlain Canal as an important catalyst for economic and ecological growth and tourism in the region; 3) Continue to support non-navigation benefits of the continued operation of the Champlain Canal to the region and to the States” [04].

In the end, the report recommended Alternative 2, which is a Physical Barrier that would involve installing a berm across the canal (filling it in), and then excess water would be rerouted. Most boat traffic would continue using either a small boat ramp, or a large boat lift, with a cleaning station. “Implementation of Alternative 2 will meet the planning objectives of this project by-limiting AIS transfer along the Champlain Canal, having a favorable cost to benefit ratio and accommodating the needs of the stakeholders along the Champlain Canal. Alternative 2 has therefore been designated the recommended plan.” The USACE estimated the cost of the Alternative 2 to be ~$18 million [04].

“...,Alternative 2 provides robust protection from AIS transfer between the Lake Champlain and Hudson River watersheds by creating a hydrologic separation within the Champlain Canal that would stop the flow in the canal in both directions. Alternative 2 is the only alternative that prevents direct water transport of AIS between the watersheds and for this reason it is the preferred alternative for the non-federal sponsor” [04].

Advance of the Invasive front. While the ink was still drying on the USACE report, aquatic invaders kept moving forward. Much of the recent concern has been on the Round goby (Neogobius melanostomus), a small bottom-dwelling fish from Europe that ended up in the Great Lakes after being transported in freighter ballast water [10]. This fish out-competes native fish, eats the eggs of other fish, and can be a vector for disease. It was first identified in the Great Lakes in 1990, and it has had a significant range expansion that has threatened the fisheries in watersheds adjacent to the Great Lakes.

One place that is threatened is Lake Winnebago in Wisconsin, which is connected to Lake Michigan (which has Round goby) by the Fox River (which does not). To protect the fishery in the lake, the Wisconsin DNR and the Fox River Navigational Authority (FRNSA) closed the Menasha Lock on the Fox River in 2015 to prevent upstream migration and fish passage; it has not reopened. A barrier system is currently being evaluated so the lock may reopen to boat traffic [11].

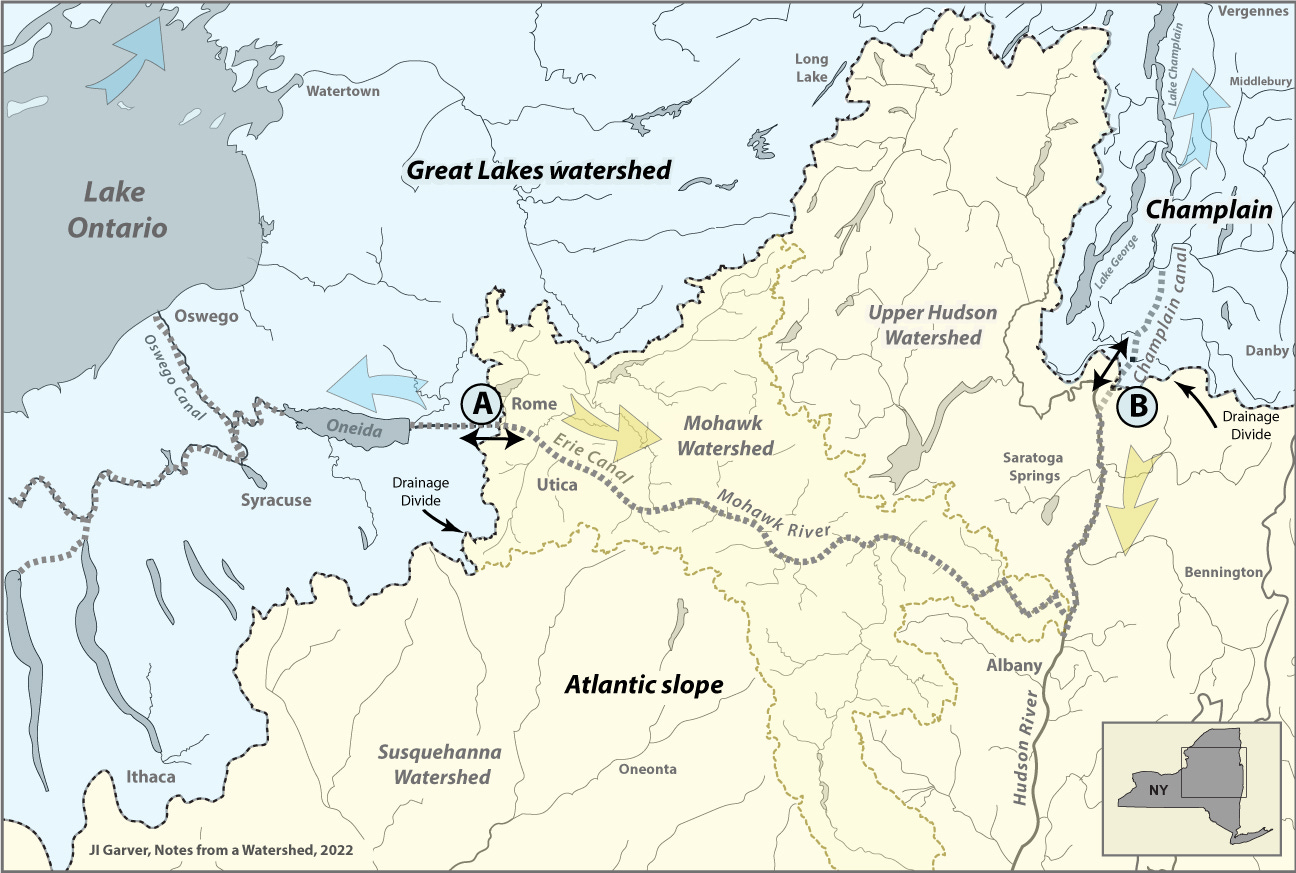

The Erie Canal and Champlain Canal are pathways for aquatic invasive species (AIS) because they connect different watersheds. We need to be designing canal barriers that will allow recreational boat traffic while containing AIS. A key step in preserving and protecting Lake Champlain is an effective barrier on the Erie Canal, which is the source of many Invasive species in the Mohawk-Hudson In this diagram the Atlantic slope basins (Mohawk-Hudson, and Susquehanna) are hydrologically separated from basins of the Great Lakes that drain into the St Lawrence seaway (except by canal connections). Arrows indicate the general direction of natural flow of water in these watersheds. “A” marks the watershed divide on the Erie Canal at Rome, and “B” marks that divide on the Champlain Canal, which is between C8 and C9.

Obviously another invasion front of the Round goby is the Erie Canal, and to some extent much of the connected inland waterways in NY State. The fish appear to have entered the canal from Lake Ontario, and then navigated the Oswego Canal to Lake Oneida by 2013. They were first reported in the Mohawk watershed in 2014, and by 2019 they were well established in the entire main stem of the Mohawk (see this Watershed post [12]). Thus this pathway took them out of the Great Lakes watershed, over the drainage divide at Rome, and into the Mohawk-Hudson system, which is on the Atlantic slope. Careful study by direct capture and environmental DNA (eDNA) analyses by Scott George, Barry Baldigo, Scott Wells, and other colleagues at both the USGS and the NYSDEC clearly showed the forward progression of these fish in the last few years [13,14]. By 2021, the fish was recognized throughout the entire main stem of the Mohawk River, and captures occurred in several places in the Hudson River [15]. Is the Round goby headed for the Champlain Canal and Lake Champlain?

A Round Goby caught by a fisherman in the Mohawk River in September 2022 (Photo: JA Smith).

Gobies in the Hudson: time for action. The initial capture of Round gobies in the Hudson in 2021 ignited a relatively rapid response because it was now possible, and in fact likely, that they would soon expand their range farther and enter the Champlain Canal, a primary invasive pathway to Lake Champlain. Subsequent work through the fall of 2021 resulted in the capture of 112 gobies in the Hudson River, mainly from Albany, but also from Coxsackie, and Poughkeepsie [both on the Hudson south of Albany see 15]. These numbers represent a relatively rapid establishment in the section of the Hudson River downstream from the Erie Canal. Richard Pendleton and colleagues, who just published the Hudson River seine survey, wrote: “...the potential and rate of upstream movement towards Lake Champlain remains uncertain, yet the ability of Round Goby to traverse upstream through locks and around dams has been demonstrated by its movement through the two downstream-most locks on the Fox River, WI (USGS 2022a - [see 21]) and in the central portion of the Rideau Canal, Ontario, Canada” [15].

Given these new numbers of Gobies in the Hudson River, it was clear in early 2022 that the State needed to address this threat before the Canal opened in the spring of 2022. Would an emergency closure occur? Would partial measures be enacted? Or would nothing happen and we would go back to business as usual on the canals?

Many concerned stakeholders wrote NY Governor Hochul in March 2022 about the pending decision concerning the Champlain Canal. One of those stakeholders who wrote the governor was David Strayer, a well-known and distinguished scientist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies. “The discussion about canal barriers is sometimes focused on the problem of keeping round goby out of Lake Champlain. This is an important consideration at the moment, but canal barriers should be designed with the broader goal of preventing the movement of all harmful species from moving in either direction through both the Erie and the Champlain canals. We are facing the Round goby today, but will face other species in the future” [16].

I too wrote to the Governor in March 2022, and urged her to take a holistic approach to controlling AIS in the Mohawk-Hudson. I pointed out that the Champlain Canal issue is urgent because we have not addressed AIS in the Erie Canal, and I made two points regarding the Goby and the Erie Canal: 1) “We need to contain further spread of this egg-gobbling fish in the upper Hudson and Champlain Canal, but note that an effective barrier on the ECC [Erie Canal Corridor] in Rome would have prevented this invader from accessing the Hudson-Mohawk in the first place.” and 2) “The Reimagine the Canals effort left unresolved the issue of stemming the flow of invasive species that are using the Erie Canal Corridor (ECC) as a superhighway to access our iconic waterways” [17].

In March 2022, just before the Erie and Champlain canals were set to open for the 2022 navigation season, the NYSDEC and Canal Corporation announced a Rapid Response Initiative to address the spread of the Round goby, and the focus was entirely on the Champlain Canal [18]. The multi-faceted plan included:

1) Field research on the Champlain Canal primarily using Environmental DNA (eDNA) targeted on the Round goby;

2) Modify locking operations at C-7 and C-8 (both on the Hudson side) to use a new double-draining technique and scheduled locking operations to reduce the number of lockages [this later changed to C1 and C2, see note 22];

3) Assess and evaluate mid-term protection strategies that include barrier systems such as electric field barriers and air bubblers;

4) Launch a coordinated public education campaign;

5) Develop rapid response plans in the event that further intervention is needed;

6) Evaluate economic and ecological impacts of Round goby.

To some this was a reasonable compromise because it meant vigilance and monitoring with a continuation of all boat traffic. Others felt the plan was inadequate because water would still intermingle and the double locking might not be effective on a fish that is good at hiding in small places. Note that in this rapid response the only direct intervention was the change of locking protocols: double locking (fill, drain, fill, drain), and schedule reduction. Due to stakeholder pressure, the Canal Corporation announced in May 2022 that the modified locking operations would instead occur at C1 and C2 (not C7 and C8) in an effort to keep the Round goby out of the Champlain Canal entirely [22].

Stu Gruskin, chief conservation and external affairs officer at the The Nature Conservancy in New York, felt the plan was inadequate and a temporary lock closure at C8 should have been imposed [19]. In an opinion piece that appeared in the March/April issue of the Adirondack Explorer, Gruskin wrote: “Lurking here is an important public policy question —how much risk is acceptable, and how much harm must occur, before the state implements the ‘hydrologic separation’ options recently recommended by its expert consultants to prevent the enormous harm caused by invasive species? Historically, the answer is that the risk of invasive species spreading has not resulted in effective action. Canal communities have paid the price as species such as the zebra mussel have spread from the Great Lakes to the Mohawk River, to the Hudson River, and then Lake Champlain via the canal system. These waterways are not naturally connected, and the canal serves as an artificial ‘superhighway’ for invasive species. Round goby is only the latest species to make that journey—and scientists tell us that the very destructive Asian carp is waiting on deck.” [19]

We now have parallel AIS studies with solutions for both the Champlain Canal and the Erie Canal. Both suggest that the best path forward includes barriers at the watershed divides and in both cases recreational boating will continue. In a sense this means isolating Great Lakes watersheds (including the Lake Champlain basin) from the Atlantic slope basins (here the Mohawk-Hudson).

Dan Shapley, co-director of the Science & Patrol Program at Riverkeeper also wrote the Governor in March 2022 [20]. In a simple and elegant way he concluded his letter:

“We urge your decisive action to create effective engineered solutions in the Erie and Champlain Canals to hydrologically separate the Hudson, Great lakes, and Champlain watersheds to protect native ecology while maintaining boating and commerce.”

It is time to consider a whole-system approach to addressing AIS in the connecting waterways in NYS, and we need leadership on this important problem. We will face other species in the future, perhaps the Asian Carps, and decisions we make today may well affect the future health of our aquatic ecosystems, and our fishery.

This and other Notes from a Watershed are available at: Mohawk.substack.com

Further Reading

[01] Reimagine the Canals Task Force Report. January 2020. Available here.

[02] R2 Resource Consultants Inc., 2019. Erie Canal Aquatic Invasive Deterrent Study. 296 pages. Report to the Reimagine the Canals task force. Available here.

[03] Lake Champlain Committee. Web site that details “Invasive species” that have entered Lake Champlain. Source here.

[04] US Army Corps of Engineers, Princeton Hydro LLC, and HDR. March 2022. Champlain Canal Aquatic Invasive species barrier study Phase I report (here).

[05] Appendices to US Army Corps of Engineers, Princeton Hydro LLC, and HDR. March 2022. Champlain Canal Aquatic Invasive species barrier study Phase I report (here).

[06] Thill, Mary, Feb 2010. An Invasives Barrier for the Champlain Canal. Adirondack Explorer (here).

[07] Lake Champlain Committee, 15 November 2015. Champlain Canal Invasive Species Barrier Stalled Again - Your Help Needed (here).

[08] Lake Champlain Committee, February 2016. Champlain Canal Barrier – Trapped in a Bureaucratic Web (here).

[09] Pimentel, D. Aquatic Nuisance Species in the New York State Canal and Hudson River Systems and the Great Lakes Basin: An Economic and Environmental Assessment. Environmental Management 35, 692–702 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-004-0214-7

[10] USGS fact sheet on the Round Goby (Here).

[11] Fox River Navigation Authority. 2022. “Information about electric barrier at Mensha Lock (here).

[12] Garver, JI, 2019. Invasion of the Round goby: Benthic predator threatens sport fishery but eats zebra mussels. Notes from a Watershed. (Note this post was first written in Dec 2019, but then updated in 2021.) (link here)

[13] George, S.D., Baldigo, B.P., Rees, C.B., and Barton, M.L., 2019. Expansion of invasive Round Goby in the Mohawk River-Barge Canal System. In Garver, J.I., Smith, J.A., and Rodak, C. 2019. Proceedings of the 2019 Mohawk Watershed Symposium, Union College, Schenectady, NY, March 22, 2019, v. 11, p. 18 (Download volume here).

[14] George, S.D., Baldigo, B.P., Rees, C.B., Bartron, M.L. and Winterhalter, D., 2021. Eastward expansion of round goby in New York: assessment of detection methods and current range. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 150(2), pp.258-273. (here)

[15] Pendleton R, Berdan R, George S, Kenney G, Sethi SA. 2022. Round Goby captured in 51 a North American estuary: status and implications in the Hudson River, New York. Journal of 52 Fish and Wildlife Management e1944-687X. https://doi.org/10.3996/JFWM-22-012

[16] Unpublished letter, March 2022.

[17] Unpublished letter, March 2022.

[18] NYSDEC, March 2020 Press Release “DEC and Canal Corporation Announce Comprehensive Effort to Protect New York's Waters from Aquatic Invasive Species Round Goby State to Develop Rapid Response Plan for Aquatic Invasive Species Effort Includes Research, Mitigation, Enhanced Public Education and Engagement to Prevent Spread of Round Goby Fish and Other Invasive Species to Lake Champlain, Other Waterways” (here).

[19] Gruskin, S. 2022. It’s debatable: Keeping out the round goby. Adirondack Explorer, March/April 2022 (reprinted 21 August 2022) (Available here).

[20] Unpublished letter, March 2022.

[21] USGS - United States Geological Survey. 2022a. Nonindigenous aquatic species. Available here (January 2022).

[22] See Canal Corporation Notice to Mariners for 19 May 2022. They note: “Lock C-1 will pass northbound traffic daily on the odd hours (7am, 9am, 11am, 1pm, 3pm, 5pm, 7pm, and 9pm). Lock C-2 northbound traffic will be locked through when all vessels from Lock C-1 arrive at Lock C-2” (see release here).

Invasives or more accurately opportunistic plants are plants that come to repair the land scape.

The human centric view that plants don’t travel, and that landscapes need to remain in situ or the same is the same viewpoint that is currently causing untold devastation to the earth and the already hundreds of species that we have so far destroyed.

When you get a landscape or environment that has been devistated, such as one with

A fire or landslide or massive building works like a canal nature tries to remedy the situation, or reclaim the territory, to put it in more understood by humans language. Pretty much all invasive plants have one function which is to rebuild soil and bring back life. They might need 10 years before they make way for other species to come in or they might need 100. Either way trying to work against this fundamental aspect of nature is damaging for our souls and contradictory to our long term well being as a species on the planet.

I would ask what are you fighting so hard to preserve that you have to spend so much effort on? And what would it look like in 100 years if you did nothing?

And I’m sorry but I think during these times I am simply convinced looking all around me that our management of our environment is truly out of intention and that we would do far better right now to do nothing, and look and learn for a coupe of generations.