Assisted passage for Forage Fish in the Mohawk watershed

Waterford flight is a fish ladder: April opening would benefit fish and boaters

Blueback herring, Alewife, Shad, American eel and other migratory fish are severely depleted on the eastern seaboard and dramatic steps are required to improve stocks of these critical forage fish, which are keystone species of the food chain. A key to restoration is to facilitate fish passage so that they can access freshwater tributaries in the spring for spawning. Some of these fish are using the Mohawk watershed for spawning because the Waterford flight of locks, which are part of the Erie Canal, allow access, but that access is limited by a late spring opening (generally mid May). Opening the locks in mid April would facilitate fish passage and allow an earlier start to boating on the lower Mohawk.

On 28 October 2021 US Representative Debbie Dingell (MI) and Brian Mast (FL) introduced The Forage Fish Conservation Act of 2021 (HR 5770), which is aimed at protecting forage fish and recognizes the importance of these fish to the food web in marine waters (see record of the bill here) [1,2]. The bill had been referred to the House Committee on Natural Resources. The bill now has 21 co-sponsors, and only one (K.M. Rice, NY-4) from New York. A similar bill was introduced in the 116th Congress in January 2020 (HR 2236) (here) [3]. In a November 2021 press release, the bill was praised by an interesting cross-section of stakeholders: the Pew Charitable Trust, the American Sportfishing Association, The Theodore Roosevelt conservation partnership, Audubon Great Lakes, and Water Resources and Coastal Policy.

The Act is focused on the management and conservation of forage fish, which are defined in the bill as those fish at a low trophic level that are prey for other fish, marine mammals, or birds. A key provision of the bill is setting catch limits in the marine realm, and this means that forage fish would have protection and regulation under the 1976 Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act [4]. For the Atlantic slope, the bill includes management strategies for Shad (American and Hickory), and River herring (Blueback herring and Alewife), among others. Some of my favorite fish.

In late 2021 Dingell underscored the importance of the The Forage Fish Conservation Act of 2021: “Safeguarding fish stocks from further decline is critical to protecting the marine ecosystem and strengthening coastal economies...This legislation’s science-based conservation framework for forage fish will both help promote sustainable fisheries and preserve marine wildlife for the enjoyment of future generations.” Thus the Act is aimed at more than just fish. Michelle Parker of Audubon Great Lakes said that “This bill will protect seabirds’ primary food source, to help safeguard them from the dramatic population declines we’ve seen in recent decades” [5].

Protection and enhancement of forage fish will benefit anglers. Jaclyn Higgans at the Theodore Roosevelt Conservation partnership wrote: “Forage fish like menhaden, river herring, and shad are the foundation of the marine food web. These fish serve as prey for popular sportfish, such as striped bass, speckled trout, and bluefin tuna, as well as iconic species like osprey, bottlenose dolphins, and humpback whales.” [6].

In the past, runs of River herring and other diadromous fish on the Atlantic slope have been stunning, but those days are behind us for a number of reasons, one of which is impairment of fish passage by dams. Can we resurrect and restore the historic runs of these critical forage fish? If so, what role might the Mohawk watershed play in stock restoration? In his outstanding 2013 book “Running Silver: Restoring Atlantic Rivers And Their Great Fish Migrations,” [7] biologist John Waldman explores the decline of forage fish on the Atlantic slope and emphasizes the urgency of addressing depleted stocks of these fish. In a review of Running Silver, Matt Miller suggests that “Waldman wants people to see rivers as they should be, filled with millions of migratory fish. He wants us to imagine the past, and not accept degraded rivers as “normal.”” [8]. If you have not read this book, you should.

To restore dangerously depleted stocks of River herring and allied diadromous fish on the Atlantic slope, Waldman suggests a few strategies to facilitate access to watersheds traditionally used for spawning. At the top of the list is dam removal because dams are the single most important deterrent to passage of migratory fish. Another is to improve fish passage technologies (i.e. fish ladders) with an overall strategy to facilitate passage and access to watersheds [7]. Tremendous progress has been made with dam removal, especially in Maine, which serves as a model for the eastern seaboard. Removal of the Edwards Dam (1999) and then the Ft Halifax dam (2008) on the Kennebec River in Maine resulted in an increase of River Herring of more than 1000%, and this system now supports what may be the largest modern run of River herring on the Atlantic slope [9].

Dam removal on the Hudson River has been proceeding nicely and a number of dams are coming down and watersheds are opening to fish that have been historically important for spawning. We may be seeing the beginning of a movement that results in the restoration of native habitat and a rebound of critical River herring and other forage fish. The movement to remove dams is growing, and on the Hudson this effort is partly led by Riverkeeper [10]. Recent successes on Wynants Kill near Troy NY show that dam removal can be quickly followed by spawning success of River herring [11]. The incredible renaissance may be the beginning of recovery for these important forage fish in the Hudson-Mohawk watershed.

Can the Mohawk watershed - the largest single tributary in the Hudson system - join this renaissance and play a part in the recovery and restoration of River herring and other forage fish? Fish passage into and out of the Mohawk is complicated, largely due to Cohoes Falls near the confluence with the Hudson. Historically, the Falls have been an imposing barrier to almost all fish migration with the exception of the American eel. In the past American eels were one of the most important fishes in the Mohawk to indigenous native and early settlers. It is assumed that the juvenile eels newly arrived from the ocean were able to slither up the wet rocks of the falls in the spring. But no other diadromous fish were so lucky, or so agile. So, the Mohawk was isolated by this natural barrier. Given the size of the watershed, however, the Mohawk and its tributaries offer an enormous refuge for diadromous fish provided they can have safe passage in and out to complete their life cycle.

Passage opportunities into and out of the Mohawk watershed changed when the Erie Canal was built in 1825. The early iterations of the canal, first in 1825 and then in 1862, allowed connection of the Hudson and the Mohawk through the canal and series of locks that went through the town of Cohoes, on the south side of the Mohawk. But it was in 1918 when construction of the Waterford flight, north of the River, changed fish passage significantly. This third phase of the canal involved moving canal operations into the Mohawk River (no longer alongside it), so fish only needed to negotiate the five locks of the Waterford flight to enter and exploit the entire watershed ecosystem.

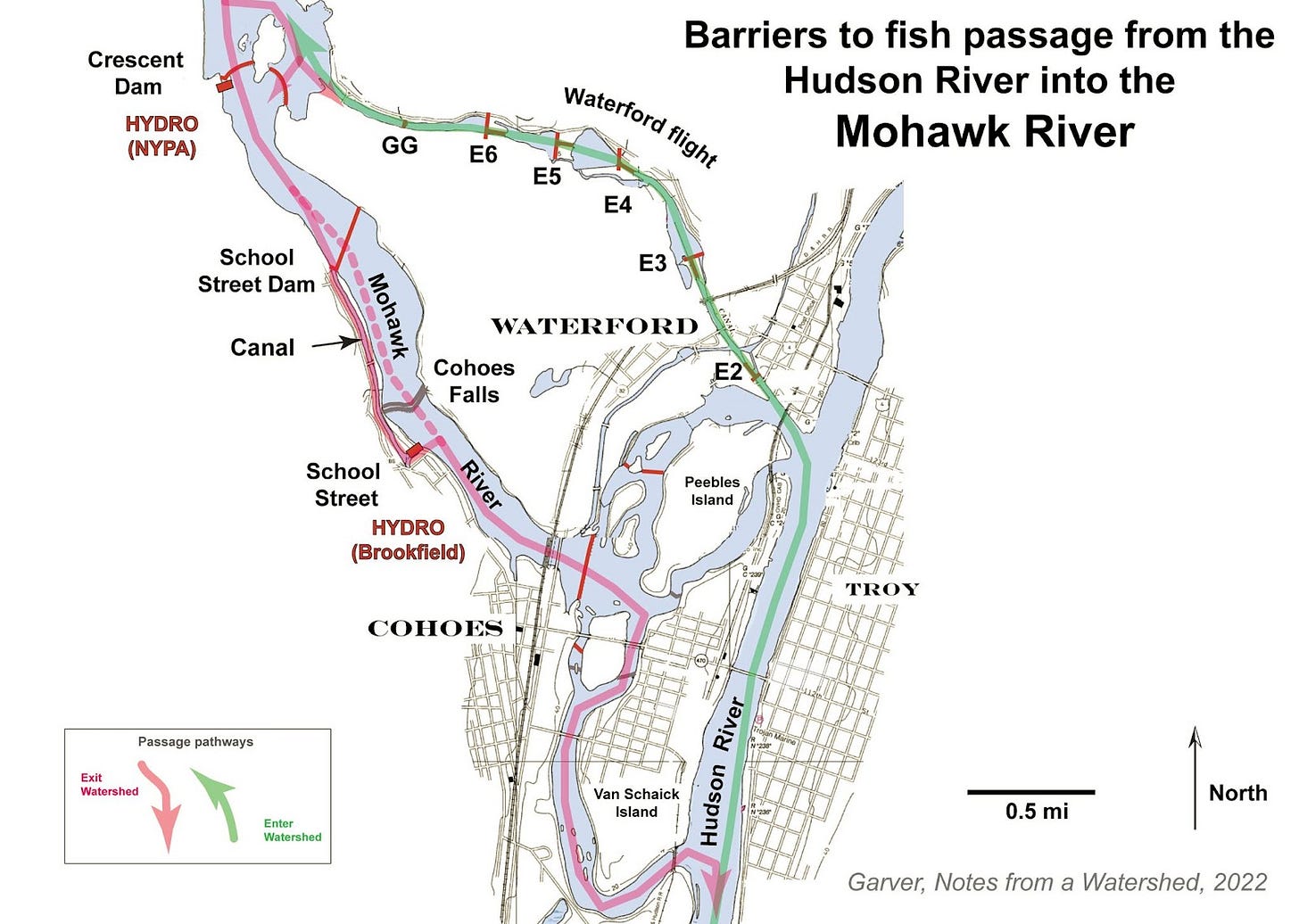

<Map of lower Mohawk> The configuration of dams and locks on the lower Mohawk at the confluence with the Hudson River is complicated for fish. “In migration” of diadromous fish entering the Mohawk in the spring must use the Waterford flight (green line), a series of locks that lift fish - and boats - 169 feet into the Mohawk River. “Out migration” of fish can also take the locks (follow green line back), but a significant fraction of fish run the gauntlet, a series of dams and hydroelectric power plants along the main stem of the River.

In this analysis we're primarily concerned with those fish that are migratory, which is a small subset of the fish in the Mohawk. These fish are diadromous, which means that they migrate back and forth between freshwater systems and the ocean annually. For the watershed this includes River herring and the American eel. River herring, which includes Alewife and Blueback herring, migrate in the spring from the ocean into freshwater systems to spawn. They both tend to travel in mixed schools in the spring, but the Alewife comes up the river starting in April while the Blueback Herring arrives in late April and early May.

In Migration. For fish to get into the Mohawk they need to use the lock system for the Erie Canal to bypass Cohoes Falls. As it turns out, both species of herring have figured this out: they have been using the Waterford flight for safe passage into the watershed for years. These fish are anadromous, which means that they migrate to freshwater systems to spawn and then most of them go back to the ocean for the rest of the year. Some of these fish, especially the Alewife, may carry on through the entire length of the Mohawk and then into the Great Lakes.

The American eel (Aguila rostrata), has a slightly different lifestyle and migration pattern. This fish is catadromous, which means it spends most of its life in fresh water and migrates to the ocean to spawn. The migration is remarkable because these fish swim thousands of kilometers to the Sargasso Sea in the southern part of the North Atlantic. After spawning in the ocean, the larvae get carried north by the Gulf Stream, and then the small glass eels work their way up the Hudson and into tributaries where they transition to elvers [17]. These determined juvenile fish work their way up rivers, streams, and creeks as far as they can go until they encounter barriers.

The Mohawk has historically had a significant eel population - the only migratory fish that could negotiate Cohoes Falls. In fact, Alplaus Creek and the town of Alplaus (near Schenectady) translates to the “place of eels'' in Dutch. Thus for eels we are concerned about upstream passage of the small elvers and also the downstream passage in the fall of large mature eels that are ready to swim out of the Mohawk and Hudson and return to the Sargasso Sea for spawning. The science-based conservation framework envisioned in the Forage Fish Conservation Act of 2021 would support passage of both the American eel, Alewife, and Blueback herring (among others).

Out Migration. Out migration of diadromous fish from the Mohawk Watershed is complicated and dangerous. Here we are considering adult and juvenile River herring, and mature American eels. We will see here that size matters because some of these fish that run the gauntlet will encounter the blades of turbines in hydroelectric facilities (there are three of them on the lower Mohawk): larger fish have higher mortality when passing through turbines.

In the last 12-15 miles (~20 km) of the Mohawk up to the confluence with the Hudson River there are three significant hydroelectric facilities that fish need to avoid to survive. These are the Vischer Ferry power project (lock E7), the Crescent power project (lock E6), and the School Street hydroelectric facility (below E6 at Cohoes Falls). The Vischer Ferry and Crescent plants are owned by NY Power Authority (NYPA), and they are currently up for re-licensing. The School Street hydroelectric facility is owned by Brookfield, and this was relicensed in 2009. These hydroelectric power plants and dams are imposing barriers to fish, but a crafty out-migrating fish can avoid the turbine blades if they use the canal locks for passage.

If a fish does not figure out how to use the locks for relatively safe passage, downstream passage involves either a tumble over the top of a dam, or passage through turbines (or both). If they enter the intake pipes and go through the turbines of one of the three hydroelectric facilities they have a reasonable probability that they will die, and, as above, the probability of death increases with body length.

Both Vischer Ferry and Crescent are up for FERC relicensing. As part of the relicensing process, the New York Power Authority (NYPA), the owner, presented an initial study report in March 2021 (here). In this initial study report there is a summary of fish passage, with separate sections on the Blueback herring and the American eel. Out-migration passage is enhanced at the Crescent facility by the use of an acoustic guidance system to keep fish away from the intakes to the turbines [12,13,14]. This system guides fish away from the channel that feeds the intake for the turbines. The system is thought to have ~75% effectiveness and therefore is likely to increase the number of fish that migrate downstream by tens of thousands [14].

School Street Passage. Out-migrating fish running the gauntlet may take the feeder canal on the south bank to bypass Cohoes Falls and in this case they end up at the School Street Hydropower facility after a short swim. Here they are faced with yet another choice: take the fishway bypass and a 90 ft plunge or go through the turbines. The School Street project is owned by Brookfield Power, and this facility was granted a new FERC license to operate in 2007. That license required fish passage, and to solve the passage issue they installed screens to keep fish out of the turbine intakeand then into a bypass (around the hydroelectric plant). This passage option for the fish was completed in 2009. Many fish end up in the fish bypass, and most fish survive the 90 ft plunge, although experimental data (with actual fish) shows that there is about a 6% mortality associated with this long drop [15].

Experiments were conducted in 2010 to determine the effectiveness of the guidance system and the lethality of the turbines at the School Street project [16]. This experiment involved capturing adult Blueback herring, implanting them with miniature (1.8 g) radio transmitters, releasing them and then seeing how well they were able to pass through the turbines or through the bypass escapement route. The fish were released at the beginning (upstream) part of the feeder canal, and receivers were used to understand their route and passage path. The experiment showed that 66 of 93 herring (71%) successfully passed the project. Of that successful group, 82% of them used the fishway, the most of the others were “entrained,” a technical euphemism that means they went through the turbines. The rest of these experimental fish didn’t make it. Given these data, we can figure that if 100,000 River herring pass through the School Street facility, 29,000 of them will probably die. Maybe that’s why so many gulls (not coincidentally, many are Herring gulls) feed in the Mohawk below the hydro facility.

Using the Erie Canal for assisted passage. The proposed Forage Fish Conservation Act recognizes that River herring, eels, and other forage fish need protection and support because they play a critical role in both the marine and freshwater ecosystems. The Mohawk watershed can play an important role in the rehabilitation of these critical forage fish because the watershed is a perfect habitat for spawning. Thus any management strategy focussed on enhancing stocks of these fish in the Hudson should recognize that the Mohawk needs to play a central role in these efforts.

Clearly we need migratory fish to continue to use the Mohawk Watershed for spawning or as a home for their freshwater part of their life cycle. The “Reimagine the Erie Canal” effort envisions transforming the canal and its operations for the twenty-first century, thus we should be thinking about environmentally sound strategies that benefit river ecology. In this case, the long-established Waterford flight is essentially a fancy fish ladder, and the fish have figured this out. Let’s help them.

If the locks open earlier to better coincide with the primary spring run of River herring and eels, we can help these forage fish in a major way by allowing the full run (April through May) access to the Mohawk, not just the tail end of the run (mid-May onwards). Thus if the locks were operated for assisted passage slightly earlier a significantly large number of fish would be able to use the Mohawk for spawning. The added benefit is that recreational boats can gain access to the lower Mohawk River earlier as well.

This and other Notes from a Watershed are available at: Mohawk.substack.com

Further Reading

[1] H.R.5770 - Forage Fish Conservation Act of 2021 (Congressional record here)

[2] Text of Forage Fish Conservation Act of 2021 (PDF) (here)

[3] Forage fish act of 2020 (Congressional record here)

[4] Magnuson-Stevens Act explained at NOAA (here).

[5] Press release (Rep. Dingell’s office) 1 November 2021. “Dingell, Mast Reintroduce Forage Fish Conservation Act to Protect Marine Ecosystem and Fishing Economy: Bipartisan Legislation Strengthens Key Protections for Fisheries and Promotes Responsible Management of Forage Fish (here).

[6] Higgins, J. 2021. How the Forage Fish act will benefit anglers. Blog. Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership (here).

[7] Waldman, J., 2013. Running silver: restoring Atlantic rivers and their great fish migrations. Rowman & Littlefield.

[8] Miller, M.L., 20 November 2013. Cool Green Review: John Waldman’s Running Silver. Cool Green Science (here).

[9] Wippelhauser, G., 2021. Recovery of diadromous fishes: A Kennebec River case study. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 150 (3), pp.277-290. (here).

[10] Foderaro, L.W., 20 January 2020. It’s Fish vs. Dams, and the Dams Are Winning: Thousands of dams across New York, many abandoned, are blocking fish migrations. A movement to remove them is growing. NY Times, article here.

[11] Kennedy, M., 11 June 2016. For The First Time In Decades, Herring Are Spawning In A Hudson River Tributary. The Two-Way, National Public Radio (here).

[12] Lenz, B. 2011. Fixed and mobile hydroacoustic detection of juvenile Blueback herring to assess avoidance behavior of ultrasonic deterrent. American Fisheries Society 140th Annual meeting (abstract).

[13] Dunning, D.J. and Gurshin, C.W., 2012. Downriver passage of juvenile Blueback Herring near an ultrasonic field in the Mohawk River. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, 32(2), pp.365-380 (here).

[14] Gurshin, C.W., Balge, M.P., Taylor, M.M. and Lenz, B.E., 2014. Importance of ultrasonic field direction for guiding juvenile blueback herring past hydroelectric turbines. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, 34(6), pp.1242-1258 (here).

[15] Apell, B., 2011. Downstream passage survival of resident fish species at the school street hydroelectric project Cohoes, NY (Abstract). Fish Passage 2011, Amherst MA. (here)

[16] Kleinschmidt, consulting group. 2010. School Street fish passage compliance compilation (392 p). Available here. See p. 22-24 in the comprehensive 2011 study on passage at School Street “Phase 1 Fishway effectiveness testing and hydraulic survey” by Kleinschmidt energy and water consulting (available here with other studies)

[17] A wonderful book on eels and eel migration is: Svensson, Patrik, 2020. The Book of eels: our enduring fascination with the most mysterious creature in the natural world. Harper Collins (NY Times review here).