1832 Cholera epidemic on the Mohawk

Prof. Chester Averill was an early Clean Water advocate

The cholera epidemic of 1832 in Schenectady was part of the second global cholera pandemic. This epidemic was partly facilitated by poor sanitary conditions that resulted in co-mingling of sewage and drinking water. Thus a critical lesson in this post is importance of clean water and the need to ensure there is no communication between sewage and drinking water supplies.

It is hard to imagine, but in 1832 the relationship between sewage and drinking water was not fully appreciated. I went down this rabbit hole of the history of sewage and drinking water on the Mohawk after looking into the 1891 Typhoid epidemic that progressively spread from Schenectady down river to Cohoes and then Albany.

I was drawn to this story because Union College professor Chester Averill played an important role in understanding the cause of the epidemic. He rightly identified contaminated water as the problem and he also offered a solution: chlorine disinfection. This suggestion, which was written in a letter to the Mayor of Schenectady, would be a milestone in drinking water sanitation. It would have been a bigger milestone if his suggestions were actually implemented.

A fuller understanding on the role that contaminated water played in disease transmission would not emerge until the middle of the nineteenth century, and thus there was considerable innovation and scientific thought directed to solving the problem. There have been seven global pandemics of cholera, and the second occurred between 1829 and 1837. The epidemic arrived in the eastern US in 1832 with outbreaks in a number of cities, notable among them is New York City, where it resulted in 3515 fatalities in a population of ~250 k.

In 1832 Schenectady had its first health officer on a part-time basis. The population of Schenectady was 4,300 people and there were 20 licensed physicians. City water was largely derived from both private and public wells. Public wells had wooden covers and apparently it was not uncommon for washing to occur at those wells, which is likely the source of contamination (Rogers, 1959). Schenectady would not take water directly from the Mohawk until 1871.

In 1832 the understanding of cholera was poor, and ideas of disease transmission and treatment were controversial. There was considerable divergence in thought as to the cause of cholera, and it would not be until the third pandemic (1846-1860) that the science was better grounded - partly illustrated by the famous Broad Street cholera case of 1854 in London (read the interesting book: The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic – and How it Changed Science, Cities and the Modern World).

But in 1832, cholera was thought to result from ‘poor environment,’ but it seemed to be clearly linked to immigration and travel – people moving around were identified as vectors. It was thought by many that it was contagious – perhaps in air - but the transmission process was unknown.

Contagion involved the idea that smell and air was primarily responsible for transmission. Thus Miasma theory apparently was responsible for the approach that the reduction of smell and odors of ‘bad air’ would reduce transmission. Because the cause was not fully understood, the solution was controversial, and that’s why Averill’s contribution is important. Because the source of the disease was poorly understood, there was also controversy as to the role that chlorine may play. Averill figured out that it was contaminated water and that ‘chloride of lime’ could work destruct “viruses” that may have been responsible for the diseases.

Clean Water advocate. Professor Chester Averill (1804-1837) of Union College was undoubtedly one of the first to advocate for clean drinking water in the Mohawk region - Schenectady in particular - through disinfection of drinking water by chloride of lime as a way to combat the spread of cholera in the 1832 epidemic (photo by author from Reed, 1837 at the Union College Special Collections, Schaffer Library).

Chester Averill (1804-1837) was a Union College student and then Chemistry Professor at Union. He entered the Freshman Class in the fall of 1824 and proceeded to study modern literature and natural science, and apparently finished at the top of his class, while being in poor health the entire time (Reed, 1837, p. 30). He graduated in July 1828 with a degree in Bachelor of Arts and upon graduation he was elected by the Association of Alumni to be a Fellow of the College and he became an ‘Instructor in College,’ and Tudor. In 1831 his Fellowship expired and he was appointed by the Board as Adjunct Professor of Chemistry and the Ancient Languages. We know quite a bit about Averill from from a publication celebrating his life written in 1837 by Reverend Thomas C, Reed entitled a Discourse on the Character of the late Chester Averill, A.M., Professor of Chemistry in Union College (herein, Reed, 1837).

In July 1832, at the age of 28, Chester Averill was promoted to Full professor and at the time had been busy teaching Botany and Mineralogy (Reed, 1837, p. 53). It was at this point the Cholera epidemic was in full swing in the eastern US, and in Schenectady. He had two primary papers in his short career, the first in 1831 was in the American Association for the Promotion of Literature and Science. The second was an important and insightful letter to the Mayor of Schenectady in 1832 about water treatment and cholera (subsequently published as Averill, 1832).

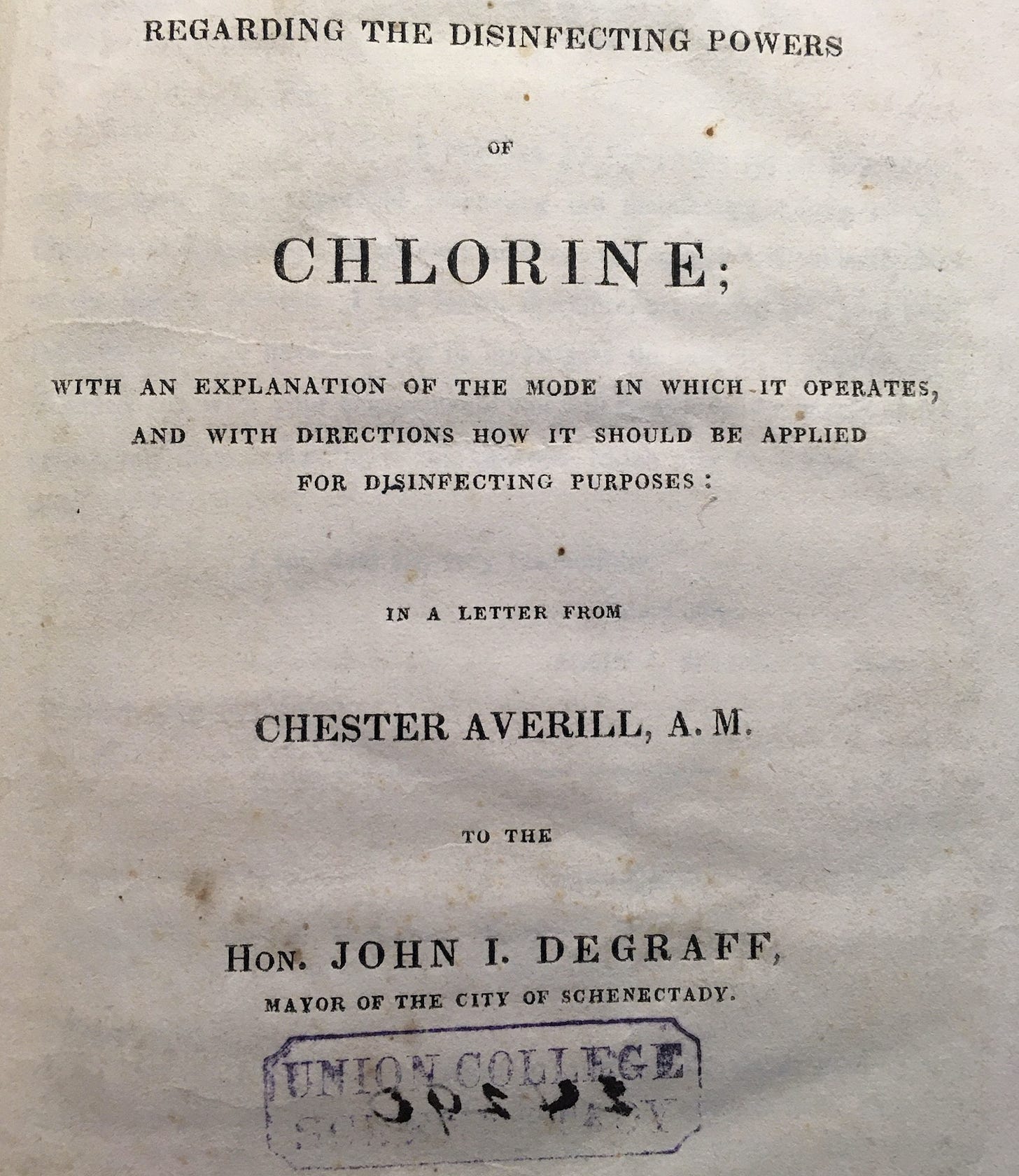

The letter to the Mayor was entitled “Treatise on the Disinfecting Powers of Chlorine” and it was written at the request of the Mayor of Schenectady Hon. John I. DeGraff, who was in his first term as Mayor but was later elected to the US House of Representatives (NY 11th district) in 1837. The request was made by DeGraff and apparently Averill wrote the letter in four days.

Averill’s letter to DeGraff is involved, but the basic massage comes though in one simple paragraph near the end. “In such cases [of contaminated water] dissolve half an ounce of the chloride of lime in about three pints of water and occasionally sprinkle the mixture around the apartment, and in the vessels as before directed.” (Averill, 1832, p. 21).

The idea received remarkable interest and support from Professor Benjamin Silliman at Yale. Professor Silliman founded the American Journal of Science at Yale in 1818 - the longest running scientific journal in the US. Silliman was interested in mineralogy, which is presumably why he was interested in Averill’s suggestion of using chloride of lime. Silliman wrote Averill in July 1832 (here from Reed, 1837):

The Chlorine-disinfectant debate must have been intense at Yale. Henry Bronson, a professor at the Yale Medical School who was a leading cholera expert at the time, wrote an argument in 1832 against the effectiveness of chlorine in the treatment of cholera. His argument, entitled “Remarks on Chlorides and Chlorine – The Chlorides and Chlorine as ‘Disinfecting agents’ and preventives of Cholera” (The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, 1832, n. 6), gives a sense of the division of thought. Bear in mind that to address the outbreak it was critical to identify the source of cholera and many held that it was transmitted in air, and thus consideration was give to using chlorine (and chlorine gas) around patients. In a brutal piece he wrote:

“It seems to be taken for granted by most non-professional and by many professional men who have thought little upon the subject, that a disease which is ascertained to originate and spread independently of a contagious influence, is of course atmospherical. This is entirely a gratuitous supposition, unsupported by a single fact, and contradicted by many obvious truths” (Bronson, 1832).

It is difficult to imagine getting this wording past an editor of a journal today. He suggested that respiration of chlorine is harmful and that in some cases where chlorine was used it could be demonstrated that there was no advantage. In this discussion was the uncertainty as to whether the disease-carrying compounds contained hydrogen, and if so whether they were reactive or not. Of course a key issue is whether the source was airborne or waterborne - thus the issue of chlorine in water or chlorine in air. But this paper highlighted a tension between the Medical community and Chemists, a point not lost on Chester Averill, who wrote:

“Chemists as well as others are liable sometimes to deduce too great inferences from particular facts; but there have been so many facts illustrating the action of chlorine upon contagious or infectious matter, as to lead them to conclude, that most if not all virus of vegetable or animal origin contains hydrogen which can be abstracted by the action of sufficient free chlorine, and thus the virus destroyed.” (Averill, 1832).

Frontispiece of the printed version of Averill’s letter to DeGraff (photo by author from copy at the Union College Special Collections, Schaffer Library).

It is remarkable to read about this scientific and medical tussle about a fact we take for granted today. But this story highlights the importance of how science works, and why there are controversies.

Chlorination would not be used in the US until 1896 when chloride of lime was added to sand filters in Louisville Kentucky (Rodgers, 1959). Today, the water supply in Schenectady is chlorinated, as are all other municipal water supplies up and down the Mohawk, the Hudson, and indeed across the country.

Professor Chester Averill married in August 1835, fathered a child, but by the winter developed pulmonary consumption (TB) and died on in the on 7 August 1836 at the age of 34.

Indeed, a career too short for this promising early clean water advocate.

This and other Notes from a Watershed are available at: https://mohawk.substack.com/

Further reading

Averill, C., 1832. Regarding the disinfecting powers of Chlorine; with an explanation of the mode in which is operates for disinfecting purposes: in a letter from Chester Averill, A.M., to the Hon John I. DeGraff, Mayor of the City of Schenectady. Printed by S.S. Riggs, 23 Union St, Schenectady

Reed, T.C., 1837. “A Discourse on the Character of the Late Chester Averill, A.M., Professor of Chemistry in Union College: Delivered at the Request of the Faculty of Said College, on the Evening of July 16, 1837” by Thomas Croswell Reed, delivered on January 1, 1837, published by Printed by S.S. Riggs, 23 Union St, Schenectady.

Rodgers, J.F., M.D., 1959, New York State Journal of Medicine, v. 59, n 15, p. 2947-2951

This and other Notes from a Watershed are available at: https://mohawk.substack.com/